As the new biopic about the actress arrives in UK cinemas, we revisit her most revelatory film, Les hautes solitudes – a haunting docu-drama, with a cameo by Nico, shot in her Paris flat five years before her death

The American actress Jean Seberg lived a life as tragic as many of the ill-fated heroines she played on screen. The Iowa-born star made her filmic debut as Joan of Arc in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan in 1957, before rising to fame as an icon of the French New Wave when she starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless two years later. She enjoyed a burst of success in the years that followed, but by the end of the 1960s her luck had taken a bad turn. A vocal civil rights activist, she was blacklisted by Hollywood and subjected to ongoing harassment and surveillance by the FBI for her support of the Black Panthers. In 1970, she suffered a traumatic stillbirth, thereafter separating from her second husband, the novelist Romain Gary. Years of mental illness and substance abuse ensued and in August of 1979, the 40-year-old Seberg was found dead in Paris – her home for many years – having apparently taken her own life.

Today marks the UK release of Seberg, a new biopic by director Benedict Andrews, starring former AnOther cover star Kristen Stewart, which provides compelling insight into the events that sparked Seberg’s downward spiral and the FBI’s complicity in her mental decline. But for those looking to delve deeper into the actress’ life and craft, one film in particular is vital viewing: Les hautes solitudes by French filmmaker Philippe Garrel. It’s a hard movie to track down – streaming service MUBI showed it as part of a dedicated Garrel retrospective last year, while the DVD can be purchased from the French distributor Re:Voir Video – but it’s well worth the effort.

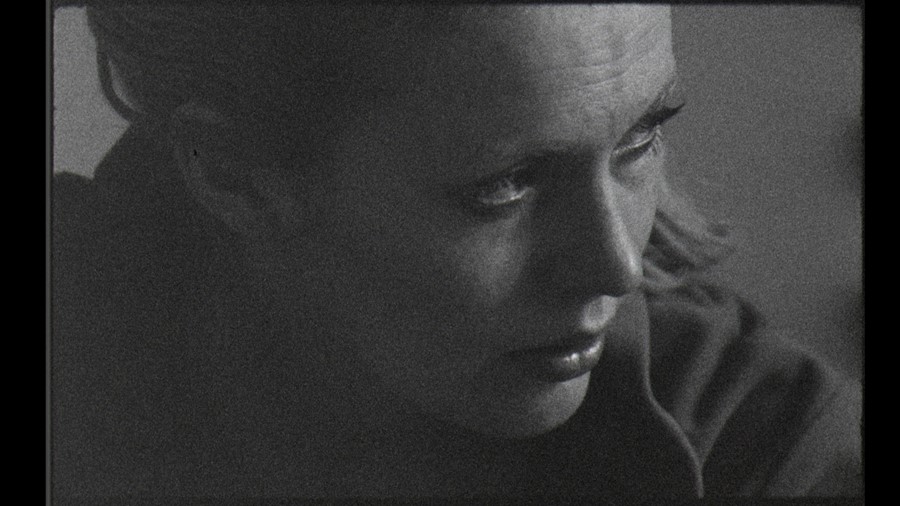

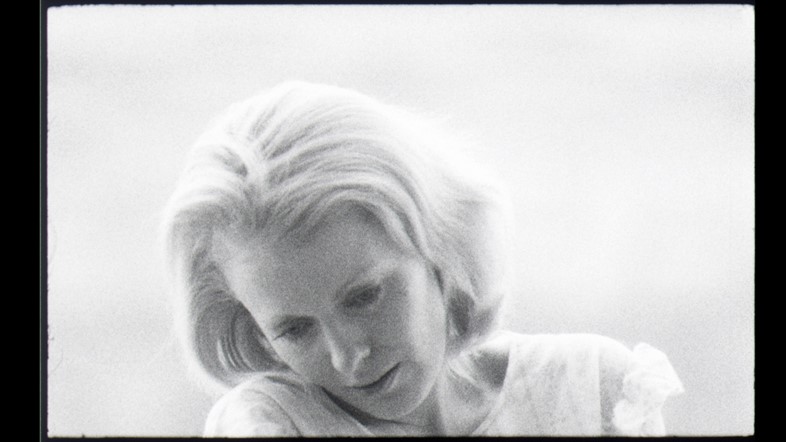

Made in 1974, during a famously reclusive and experimental spell for its auteur, Les hautes solitudes is a completely silent film, with no credits, subtitles or plot, shot in grainy black-and-white. It is a docu-drama of sorts, filmed almost entirely in Seberg’s flat in Paris and features the actress exploring a range of emotions before the camera, alongside footage of her friends and fellow actors Laurent Terzieff and Tina Aumont, as well as Garrel’s longtime muse and then-lover, Nico. At the time, Garrel was an avid fan of Warhol’s similarly silent and monochrome screen tests and their influence is easy to detect in both the film’s visual set-up and investigation of celebrity.

Garrel, who met Seberg just one week before he began shooting, has always described the project as a collaboration between himself and the actress. “The idea was to make a film out of the outtakes of a film that never existed in the first place,” he once explained. “No one thought that it was a real film, but [Seberg] was very independent and didn’t care about this. I consider Les hautes solitudes as much a Seberg film as mine.”

The movie is 80 minutes long, and deeply moving; the critic Ben Sachs aptly describes it as a study of “the crippling pain of depression and the grace one can achieve by enduring it”. A far cry from the pixie-cropped ingénue the world fell in love with 15 years before, here Seberg is world-weary, her gently lined face – although still beatific in the sunlight that frequently illuminates it – betraying all the sadness she has suffered. Filmed largely in intimate close-up shots, the footage shows the actress as both a master of the camera and her own emotions. A number of vignettes depict her staring directly into the lens – as she does so memorably at the end of Breathless – at times appearing to challenge it, at others flirting or pleading with it.

Some scenes see Seberg interacting with the younger actress Aumont – a sultry, dark-haired counterpoint to Seberg’s blonde tragedian – while others find her engaged in muted, passionate conversation with someone off screen. Occasionally, Seberg acts as if the camera isn’t there at all, seemingly disappearing into herself completely. And in these moments, it is almost impossible to separate fiction from reality. In one particularly alarming early scene, Seberg, kneeling in front of garish 70s wallpaper, begins taking pills from a bottle and stuffing them one by one into her mouth, before chasing them with wine. She then studies the page of a book before appearing to panic and calling out to Aumont who rushes into the frame to assist. Apparently, Seberg really did swallow the pills, disturbing Garrel to the point that he stopped filming for some days.

Because of its experimental, deliberately enigmatic nature, Les hautes solitudes is very much left open to interpretation, but what is abundantly clear is that it is Seberg pulling the strings. Garrel has said of the film that he was trying to capture “qualities of life, much more than qualities of style” – something he said he’d observed in both Breathless and Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1972 film, Last Tango in Paris. And it seems Seberg, ever the artist, set out to deliver this – offering up her life and art to Garrel’s lens as one intrinsically linked entity, as if painting a self-portrait on film. Five years later, she would indeed die by suicide, leaving behind Les hautes solitudes as perhaps the most enduring testament to her pain, loneliness and creative genius.

Seberg is in cinemas from January 10, 2020.

Les hautes solitudes is available to purchase from Re:Voir Video.