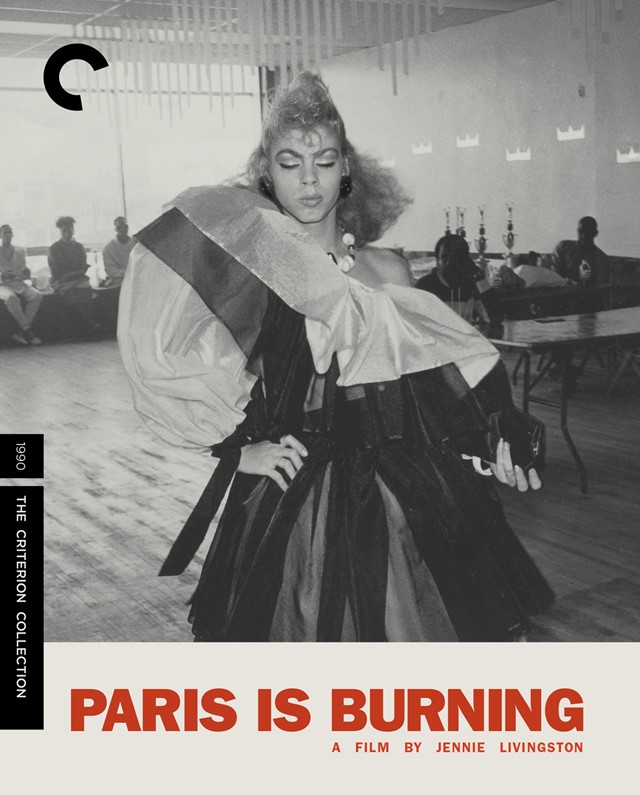

30 years after Paris Is Burning hit the big screen, director Jennie Livingston opens up about creating one of queer cinema’s most celebrated – and controversial – documentaries

If you’ve ever heard of “realness”, “reading”, “throwing shade”, it’s probably because of RuPaul’s Drag Race. But the origin of this terminology far precedes the reality-TV-show-cum-Olympics-of-drag, dating back to the ball scene of the 1980s, an underground LGBTQ black and Latinx subculture, documented – and first brought to the attention of the mainstream – in Jennie Livingston’s masterful film Paris Is Burning which, 30 years after its release, has been restored and re-released via The Criterion Collection.

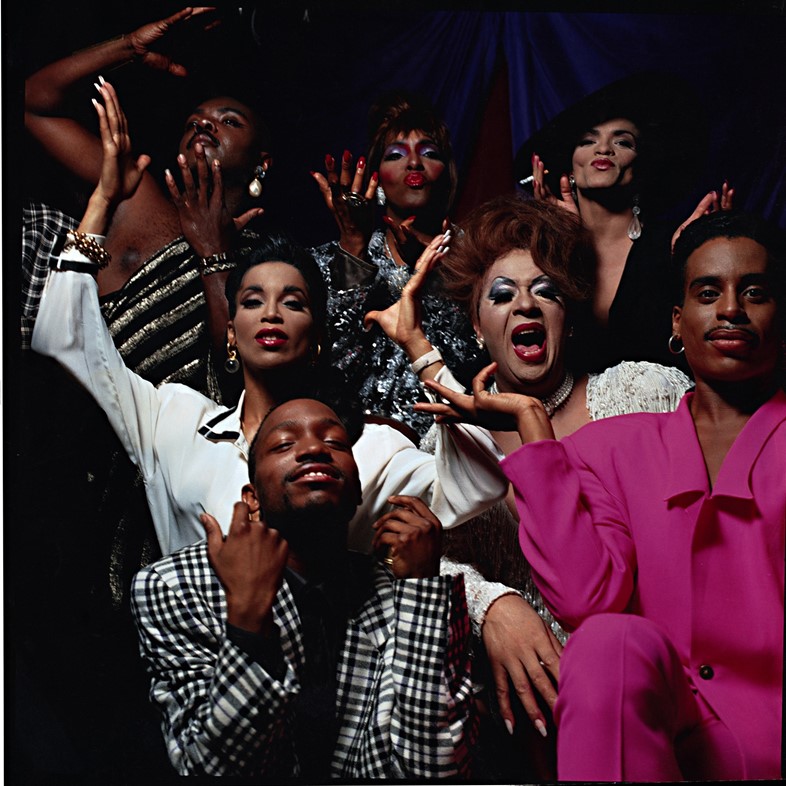

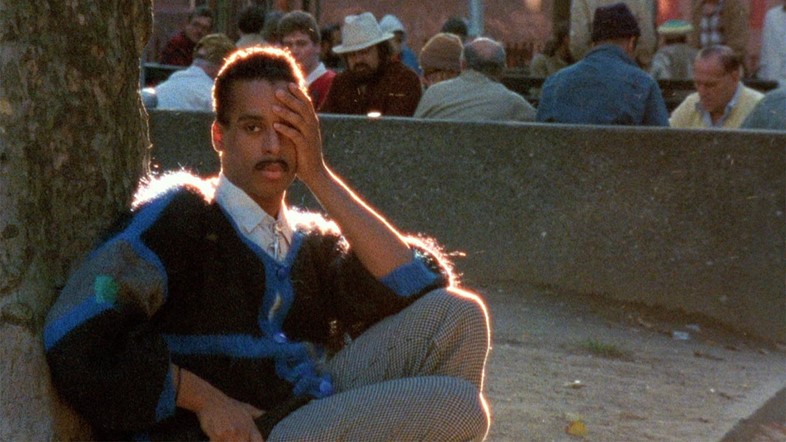

Livingston started documenting this subculture when she was just 23, first through photography, then through film, capturing the “community and spectacle, the energy” of these balls. Created in the Reagan Era – a period of extreme wealth and poverty, Dynasty and Dallas – we see this community responding to this time and the adversities it came with, expressing their identity, sexuality and creativity. Three decades on, this film is at once celebrated and controversial for its portrayal of this people group.

Here, speaking to AnOther and alongside some of Livingston’s photographs of the ball scene, the director discusses the process of filming Paris Is Burning, its reception and complex legacy – responding, in particular, to bell hooks’ criticism of the film.

Arijana Zeric: How did you get introduced to the ballroom scene?

Jennie Livingstone: I was a young photographer walking around with a camera in New York and saw some guys in the park who were voguing. I started photographing them and they said if I wanna see more of it then I should go to a ball. I was pretty amazed and spent two years speaking to people and doing sound interviews. Over time I realised this was not just a photography project, this could be an amazing film and the world needs to know about this community and spectacle, the energy of the balls and of course what the people in that had to say about their own identities and their world but also about the larger world in which the ball subculture lives.

AZ: Was it difficult to film at that time?

JL: We didn’t have money to make a film, so I did a film a trailer in ’86 and finally, in ’87 we raised enough money from a TV station called WNYC. Madison Davis Lacy, who is the exec producer of the film gave us enough money to shoot and we had to raise the rest. So it was made over time. If it were now and you had prosumer cameras or iPhones, you could have just hung out indefinitely, but at that point, the only thing to shoot a documentary on was 16mm film which is incredibly expensive. We were very judicious, so that’s why formally, the film is more about interviews and events and not so much other stuff.

AZ: Did you ever imagine that your documentary would be the success that is was?

JL: Absolutely not! At that time there weren’t films about queer life, there were very few films about African-American and Latinx life, particularly if it was a subculture of people of colour. Those subjects just weren’t considered interesting to audiences. Madison Davis Lacy, who is African-American, saw familiarity in the way the culture worked and the way people express themselves. The EP from the BBC, Nigel Finch, was gay, and was also familiar with aspects of the culture. So many people who gave us money intuitively saw that there would be audiences. But it’s always surprising for anybody to see a story that has nothing to do with you, yet has everything to do with you. And that is the power of storytelling in cinema.

AZ: With TV shows such as RuPaul’s Drag Race and Pose, drag is having a great resurgence of popularity at the moment. Do you watch Drag Race and what do you make of it?

JL: I’ve seen Drag Race and I know RuPaul, we used to work out at the same gym back in the 80s called MegaFitness. I think Drag Race is obviously a very different world, but I’m thrilled. I think it’s great that there is something in popular culture that shows people there is fluidity in something that’s traditionally binary as gender. Those images in Drag Race or Pose help make the world safer. Because some of the world leaders we have now use hate speech in a way that goes directly to the hands and minds of violent people. If you see what is going on in my country, India, Hungary or the Philippines ... So when the media can become a positive force of normalisation, acceptance and celebration of people who are not gender normative then it’s a force for good.

AZ: To what extent would you say has drag culture changed?

JL: I think acceptance has changed. But everything shifts, even the ball world. The people shift, the music, the rhythm and some of the categories are different. But it’s hard to generalise because people are still being murdered all over the world. Are people being more accepted in NYC? I don’t know if I can answer that. Urban meccas have always been a place for people to come and be different.

AZ: bell hooks has criticised the film as being exploitative and too focussed on the spectacle side of this subculture. How would you respond to that?

JL: She felt the identities in the film were not resonating with the white audience, that they were othered and therefore othering her. She also felt the ball world itself wasn’t politically in a direction that she would like. It was a kind of personalised community, that she didn’t like politically. And that’s fine, I can’t argue with that. What I have an issue with, is that she talks about white critics who got it wrong. She never acknowledged the popularity with queer black critics. She didn’t see how valuable the film was to queer black audiences, she didn’t acknowledge they needed a hit. So it’s fine to say ‘I as a straight black woman have issues with the film’ but I didn’t think it was entirely cool to silence the black and Latinx queer people who gravitated towards the film and got a lot of sustenance from it. So my position as a filmmaker is [that] not everyone is gonna love the film and people are gonna have criticism, legitimate or otherwise, but that’s the kitchen you’re cooking in.

AZ: Do you have any favourite memories from the shoot?

JL: One of the things that’s funny about the re-release was that I got to spend some time with all the outtakes which I have not seen for years. In one scene we were interviewing Dorian Corey in her apartment in 150th and St Nicholas in Harlem which at that time was a pretty borderline neighbourhood. She was talking to us about religion because the ballrooms in some ways were like churches. Suddenly we hear gunfire and she looks at the camera and says: “Oh ... Gunfight at the OK Corral”. It was pretty amazing to see that again.

AZ: Some figures, such as Octavia, were greatly influenced by the images projected by fashion campaigns and wanted to be household names. Did you get the sense that contestants were somewhat out of touch with reality, aiming for a life that was too out of reach?

JL: It’s funny you mention that because when we were looking at the outtakes, we saw this one interview with a queen who certainly was out of touch with reality and this individual seemed to be not well mentally. That’s why we left it out of the film initially because that’s not where we wanted to go. My feeling was that the people in the ballroom were not out of touch, but I think the aspiration to have wealth and fame is very American and was very much on people’s minds in the 80s. No one wants to have social policies that will benefit everyone because each American thinks if I become a billionaire, why would I want to take away billionaires’ rights? So there is a disconnect in society.

AZ: Dorian Corey, who gives us insights into the history and terminology of drag culture, says that in the end that life should be just enjoyed. Is that the message of ballroom?

JL: She is also talking about your aspirations versus what actually happens in your life. That’s why she’s such a universal voice. She is saying ‘Go for it, and if something good happens, awesome. But everything you want isn’t gonna happen.’ I think it’s what the ballroom says to people.

AZ: After Dorian died, a preserved body was found in her closet which apparently had been there for 15 years. How did that make you feel, knowing there was a dead body [there] while you were filming?

JL: The closet thing was pretty amazing and crazy because I was in her apartment and I was with her when she was dying. She lived in a basement and moved up on a fourth-floor walk-up meaning they had to carry the trunk with the body up five flights. So that was really surprising ... Whatever happened it was probably self-defence. Dorian probably had the skills to embalm bodies as she trained with a mortician as a young person. So I think she just said, ‘I don’t wanna go to prison here so ...’

AZ: Have you ever considered doing a sequel?

JL: I think sequels are destined to be a let-down. Can you think of a sequel you enjoyed more than the first one?

AZ: Godfather 2, Terminator 2?

JL: (Laughs) Exactly! I wish I could do that. A lot of people have passed away, in a way that’s the story you could tell. But it would be a hard story to tell and tell well.

A newly restored version of Paris Is Burning is out now via The Criterion Collection.