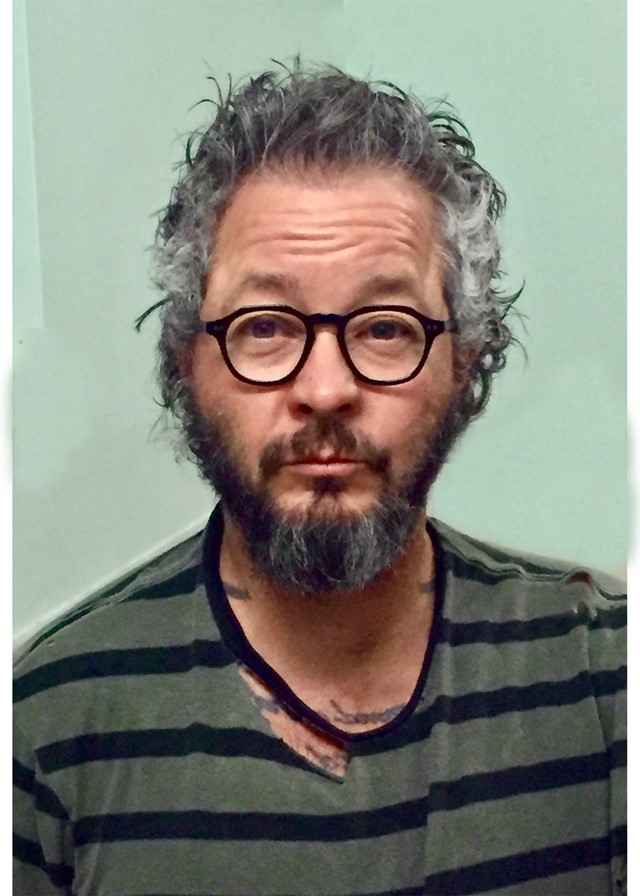

Artist and writer Harry Dodge speaks to Amelia Abraham about the making of his new book My Meteorite, opening up his personal life on the page, and what’s on his own reading list

This article is published as part of our #CultureIsNotCancelled campaign:

When the artist Harry Dodge ordered part of a meteorite on eBay, he didn’t realise it would become a kind of proxy for his thoughts about the mysterious patterns of matter across time and space, or one influence for a book about the interconnectedness of moments, people, and things. The titular My Meteorite is less a memoir and more a thought experiment that puts together fragments of Dodge’s life – particularly its greatest coincidences – like a jigsaw puzzle, to try and find meaning.

Dodge’s partner – the writer Maggie Nelson – describes his book as Nabokovian. “Chess problems demand from the composer the same virtues that characterise all worthwhile art: originality, invention, conciseness, harmony, complexity, and splendid insincerity,” wrote Vladimir Nabokov. Dodge’s book contains these qualities and is like a game of chess in itself; My Meteorite argues that coincidences connect moments, people, things through time, yes, but it also reminds us that endings are not fixed, if just one thing had happened differently, everything thereafter might have changed.

In that sense, the book and its vignettes – from sexual encounters to meetings with Dodge’s birth mother to raw scenes of the artist’s father’s death – capture the spirit of life’s wild unpredictability. But expect documents of conversations with great artists too, as well as a lot of heavy theory, and a strong occupation with technology. “We’ve been on the move – mixing with each other and things – forever,” writes Dodge, who pays this forward, pondering how humans might interact with AI in the future.

Below, we talked to Dodge over the phone from his home in LA about switching his energies from film and sculpture to writing, opening up his personal life on the page, and what’s on his own reading list.

Amelia Abraham: How did My Meteorite come about – was there a moment when you decided to write a book, per se?

Harry Dodge: Yes I knew what I was doing [laughs]. I did decide. Although the whole time I was saying to people, “I’m pretending to write a book” so I guess there was a weird sort of prophylaxis there, some psychic sheltering. But I definitely wrote it with purpose. Normally I spend about 35 hours a week in the studio, making stuff, and in the beginning of 2017 I switched all of that energy over to writing. I wrote in earnest for about a year, working through notes from 2016 and writing out things synchronously too, in 2017. Writing the book was, you know, my relationship with language made manifest: joyful, ecstatic. I was happy to take language up as a tool again, in this sustained fashion. I wanted to write out some of the research I was doing on materiality, and on machine intelligence.

AA: For a book you were pretending to write, it’s very good! It’s also quite a nebulous book; I wonder, how do you describe it to people you meet in passing?

HD: [Laughs]. It’s a hard book to describe, you’re right. Generally I tell people it’s a meditation on matter, and a book about bonding or, say, love. It uses as its spine three related narratives: one, my dad’s death and decline from dementia, another is rekindling this mysterious relationship with my birth mother, and the third one is the story of my experiment with solitude and sociality: the vagaries of being a hermit artist, and then there’s the meteorite which provides a central meta-narrative.

“I know it’s hard for some people to believe but these constructions – narratives we curate and craft and shine up and frame and lay out – I think of that as artwork. It’s not my private life at that point” – Harry Dodge

AA: It’s also a lot about serendipitous happenings …

HD: I think the book takes up the question of whether or not things are “coincidences” – which is to suggest that, despite it being highly improbable, certain rhyming events have aligned – or whether there are patterns, sometimes legible, that issue from natural laws, known and unknown – forces which, in the book, borrowing from Brian Massumi, I call the “habits of matter”. Matter repeats, it has stuff it likes to do. Maybe matter makes these macro-patterns ... Maybe they’re caused by tendencies we haven’t figured out yet, that therefore seem “magic”, but are actually somehow attributable to rhythms in the cosmos. I think of this as an earthy, kind of rational proposal, which is not to denigrate anything that’s palpable but rather the opposite: I aim to bring a sense of absolute marvel to what we otherwise think of as mundane or human.

AA: The book is a lot about family – your parents, adopted and birth, your own children – were there any reservations writing about that?

HD: I’m quite a private person, yes. I know it’s hard for some people to believe but these constructions – narratives we curate and craft and shine up and frame and lay out – I think of that as artwork. It’s not my private life at that point. The distinction is, for me, clear. Information that people have, personal stuff I haven’t polished up, worked on ... That’s different. Yuck, awful. But books, writing, these things are constructions, missives from an artist to the world, meant for sharing, meant to prompt sociality. Art. Some people think of it as a representation of a life, but I tend to think of it as something wholly unrelated. I mean there’s a history here. Hervé Guibert, Eileen Myles. A playing with the mode or idea of the fictive – they both have made it into a layering tool, something “meta”. A slippage that itself makes meaning.

AA: Is writing about death as cathartic as people would have us believe?

HD: I’m not sure that I found it cathartic. I would get it down at great emotional expense, honestly, write it out, and then avoid it as much as I could in read-throughs. I would only go back in to edit when I was absolutely ready to be there. The deaths, honestly, never got easier to edit. Reading those sections for the audio book was a whole crybaby circus. Super tough.

AA: You said it was a big shift channelling a great deal of your energy from making art to writing – is it a help or a hindrance to be with another writer?

HD: It’s fantastic to have had the privilege of hanging around with Maggie all these years. Every day since the day we moved in together, we stand in the kitchen having these big debates – it’s a storm of thought. We’re both delighted to be on the edge of a question that’s unanswerable, so that’s super generative. Whether or not Maggie is a writer is sort of beside the point; it’s important for me to be with someone who has a creative practice that’s demanding, you know, something they’re unambiguously committed to – because otherwise my passion for practice, something that borders on obsessive, can be alarming or, you know – painful. Maggie and I have a lot in common, this feverish making, but also this sort of bird-dogging into hard questions.

AA: There’s a lot of musing on posthumanism and AI in the book. When did you get so fascinated with machines, and why do you think you are? Especially when you also say you’re a Luddite!

HD: For many years I have been a misanthrope and a Luddite, weirdly. I’ve always thought that humans are assholes that do dumb crap and ruin everything. At the same time I’ve always considered humans to be animals and continuous with nature. The thing is: I couldn’t have it both ways. I lay this out in the book more eloquently but if nature is so perfect and innocent, and humans are so awful, but also continuous with nature, well that’s a sort of paradox.

A few years ago I thought: One, if I want to be an interesting artist and nimble thinker I can’t always be idealising the past. What’s next? Two, if humans are continuous with nature and if the habits of matter actually generated planets, the cosmos, creatures, plants, et cetera and as humans then, we’re blobs of matter continuous with nature, then the distinction between nature and culture falls away. I ended up thinking of human invention as somehow comparable to leaves on a tree; something inevitable, something I have to deal with as natural. In fact, by this logic, nothing is unnatural. These new thoughts slammed into the old Luddism in me and I had to start reading and thinking and writing to test out this new paradigm, which is why some of the book takes up that research and the transformation of my thinking.

“The deaths, honestly, never got easier to edit. Reading those sections for the audio book was a whole crybaby circus. Super tough” – Harry Dodge

AA: You reference a lot of theorists and philosophers ... There’s a lot to go away and read ... If you hope someone reads one thing next, referenced in My Meteorite, what would it be?

HD: My favourite book of all time is Poetics of Relation, the Édouard Glissant book, it’s just fantastic. A compendium of essays, rendered poetically, the book deals with the paradox of interconnectedness and specificity. Glissant is interested in difference and at the same time in this idea of totality by which I think he’s referring to the fact of cosmically scaled mutual constitution, plural subjects, and ecstatic contamination – we make one another, we interpenetrate. And I think if your interest is piqued by the AI stuff, try reading Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom. A fascinating book, very thorough and also very philosophical about artificial intelligence, meditates upon the possibility that human invention will purposefully or inadvertently produce unimaginably powerful superintelligent creatures.

AA: What are you reading at the moment?

HD: Well, weirdly, as soon as I finished My Meteorite I started writing another book because I enjoyed the practice so much and I didn’t want to stop. It may never see the light of day, it’s super weird, a kind of sci-fi farce. It’s going to be a short novel. So in preparation for that I read a bunch of short novels – Robert Walser’s Jakob van Gunten, I read Olivia Laing’s Crudo, and I read Crazy for Vincent, by Hervé Guibert.

AA: You have a conversation with Martine Syms towards the end of My Meteorite, about whether someone will invent immortality pills. She says she wouldn’t want them, and you say that you don’t want to die. What’s your favourite thing about being alive?

HD: That’s such a great question it makes me want to cry! My first thought is that I love to think. Thinking is a full body pleasure – thinking things through, asking questions, trying to work things out. A kind of joyful puzzling.

My Meteorite by Harry Dodge is published by Penguin.