We can all agree: nudes are fundamental. As old as cave paintings, “the nude” unsurprisingly exploded after the sexual revolution – reflecting our innate thirst in new and exciting ways. National outlets like Playboy and Hustler disseminated varying degrees of erotica with record abandon. Primarily targeted at straight, male eyes, this semi-mainstream pulp found a notable exception in Playgirl – the magazine of adult entertainment for women, launched in 1973.

Sparked by a convergence of the sexual and women’s revolutions, Playgirl was in some ways ahead of its time. In lifting the veil on the disproportionately verboten “male nude” – packaging it in well-lit, passably artful centerfolds – the magazine challenged norms that the sexual revolution did not – namely ancient gender gaps vis-à-vis modesty, desire, and power. However audacious, the Playgirl brand paled in size to that of Playboy, possibly muddied by concurrent gay-liberation forces: by not explicitly courting a male audience, the magazine seemed to reinforce a kind of glass closet.

An early memory of mine illustrates the magazine’s contradictory allure. Once, while idling at my mum’s hair appointment, I (a kid) casually reached for some reading material – a smooth men’s torso resting atop the magazine stack ... Playgirl! Before I knew it, a breathless commotion had erupted: mum, the stylist, the entire salon lunging to intercept my wandering, impressionable hands. The episode, besides evincing my latent yet irrepressible homosexuality, also locates Playgirl’s slippery place in pop culture: acceptable titillation one minute, contraband the next.

When I learned that Playgirl was poised to return in 2020 – this time as a print-centric glossy – I was, you might say, titillated. But now that I work in media myself, I was also curious about where and how the magazine would position itself. Would they traffic in girl-boss empowerment? Or capitalise on post-sex-revolution innovations like OnlyFans? “Playgirl” trademark aside, would they flout gender and sexual binaries altogether?

We won’t know until the magazine launches this autumn. But one way to imagine what Playgirl can be is to remember what it was. Here, we set out to do so, interviewing a range of past and present authorities – from an intern-turned-decorated-author to the publisher charged with resuscitating the brand.

Jack Lindley Kuhns, Playgirl publisher, 2016–present

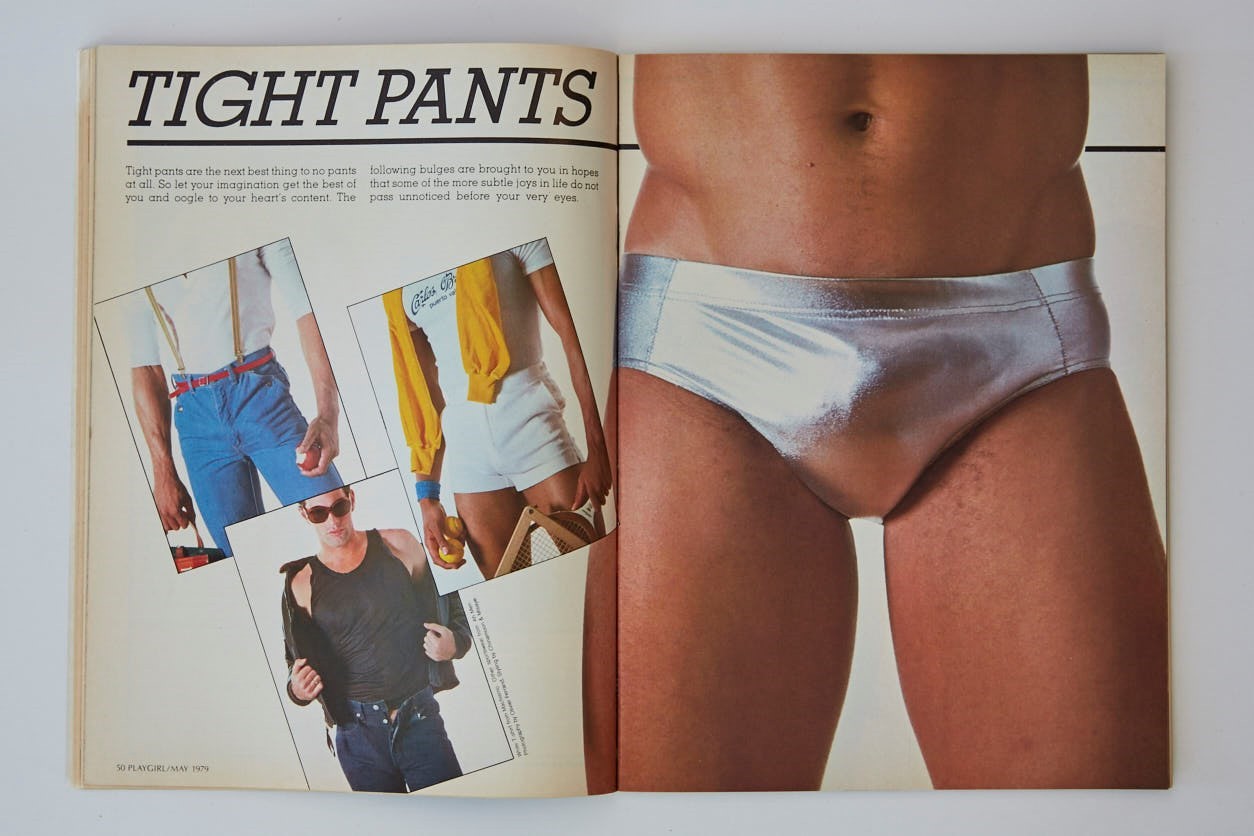

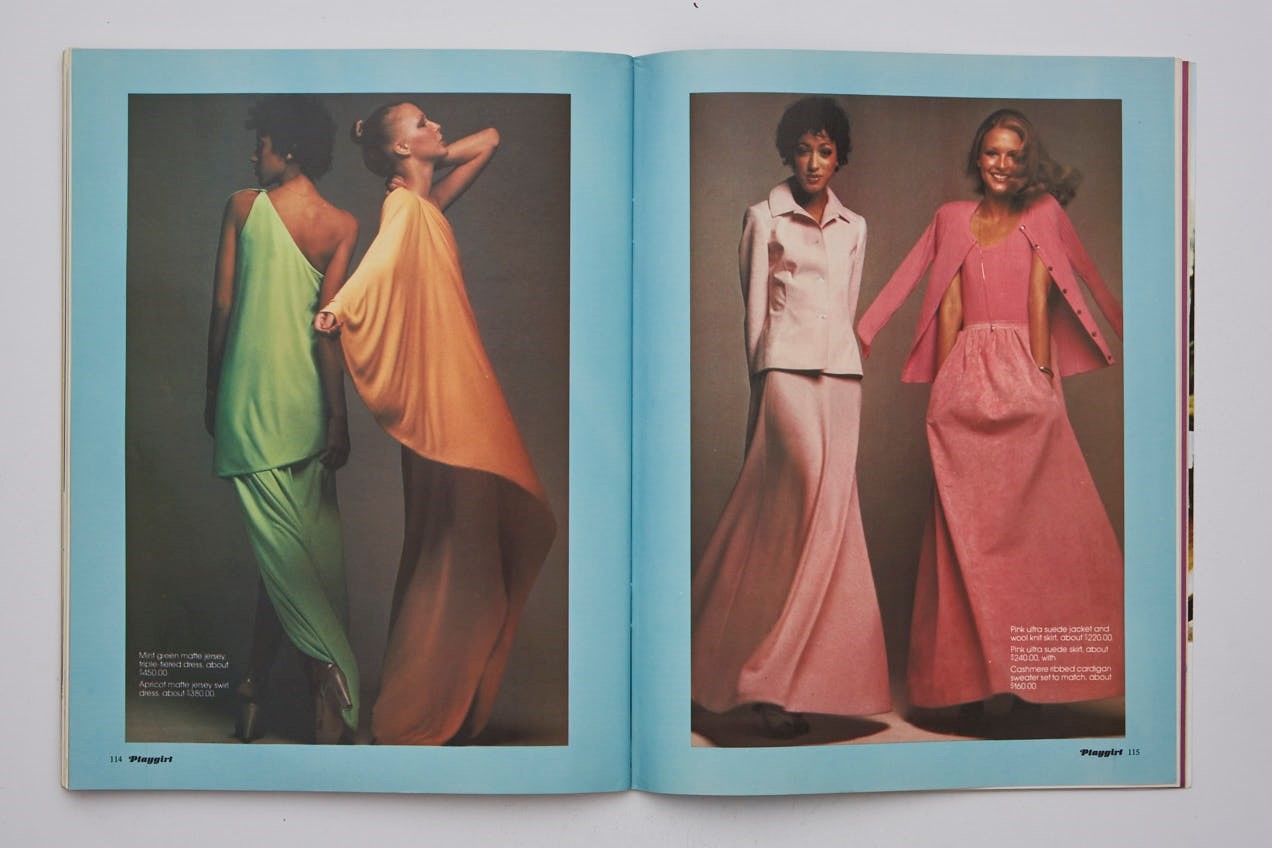

“I acquired the publication on December 16, 2016, just after the election. In hindsight I didn’t know anything about [the brand], but I was drawn to it visually – especially to the early issues. 70s Playgirl [feels the most contemporary]. I love the fact that it was provocative, but also included beautiful fashion spreads as well. When I started collecting old issues, I saw that ‘Entertainment for Women’ meant much more than pictures of naked men. The first issue, from June of 1973, [defines a ‘Playgirl’] as, ‘A woman who loves [and] takes care of herself ... but at the same time enjoys sex and a good lifestyle ... A ‘Playgirl’ deserves to look at today’s most exciting males – those you desire, and whom you wish to reach out and touch ... To experience in any manner that is pleasing to the individual ‘you’.’

“I don’t have any hard facts about this, but I think that reading the magazine was done very much in private. Even so, the innocence of the nudity – the straightforwardness and simplicity of it – is really what drew me in. To me, the centrefolds were always about the art – art with guys who happened to be naked. There were no [bad] intentions ... When I look at [them] today, it’s just beautiful imagery.”

Kuhns is the publisher of Playgirl magazine.

Michael Hodgson, art director, 1983

“I’m 67 and basically retired now, but I’ve had a good career. I started in London when I was 22, at Harper’s & Queen magazine, [which later became Harper’s Bazaar UK]. I’d always wanted to live in LA, so I called my friend [from art school] who got me a job at a magazine out there: Playgirl. I thought it was the female equivalent of Playboy, but it was a long way from that.

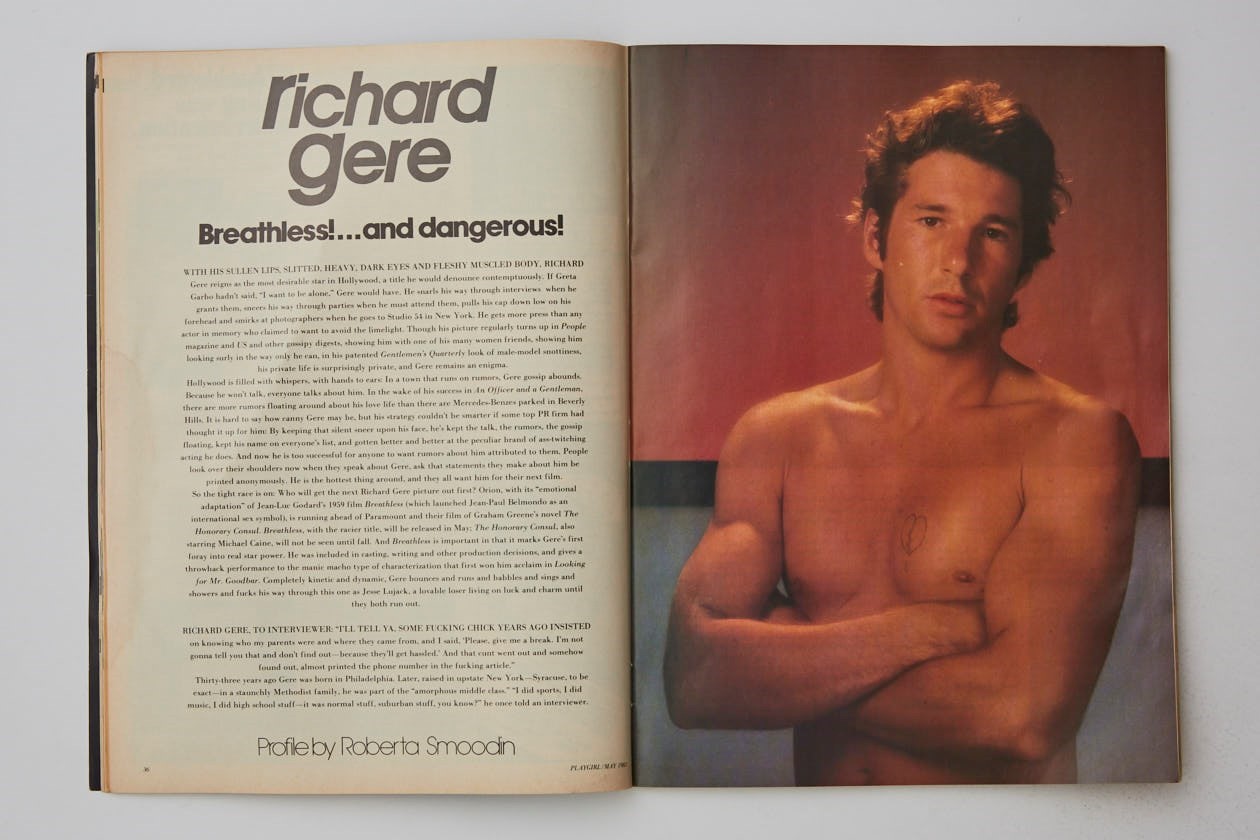

“I was the art director, so I designed all the spreads. It was my job to visually reflect the magazine’s mission statement – which was to offer a liberal, open-minded vision of female sexuality. [I did so] by getting good photographers to work for us – Philip Dixon and Matthew Rolston, who worked a lot for Interview. And by choosing good-looking models, too.

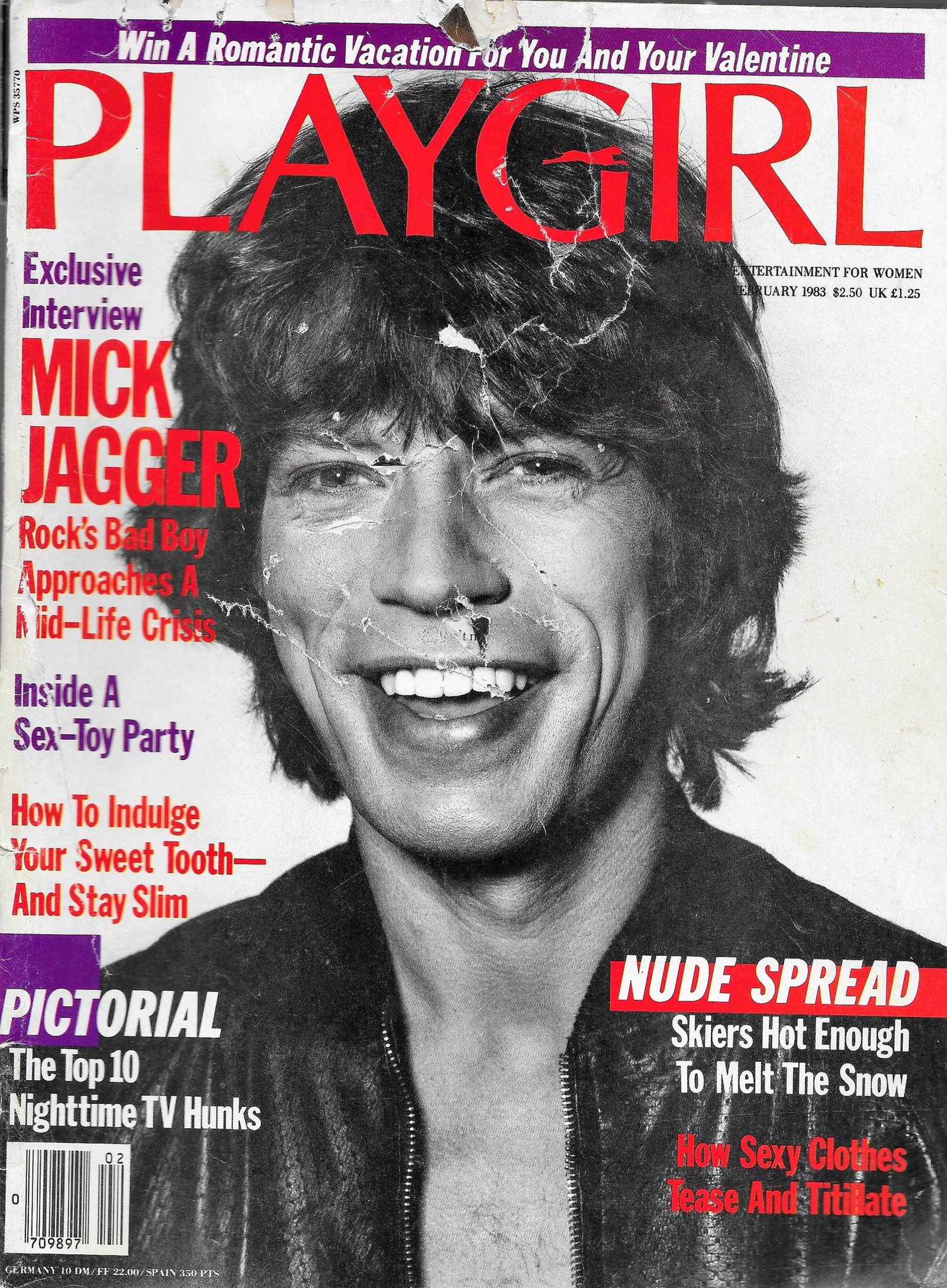

“My most memorable cover was Mick Jagger, for the February 1983 issue. He was considered the go-to sex-symbol at the time. The coverline was, ‘Rock’s Bad Boy Approaches a Mid-Life Crisis’, and the art [was pick-up] photographed by David Bailey, with whom I shared an agent at the time. The images show Mick in a black leather jacket ... No nudity. I quote-unquote ‘forgot’ to send [the print] back to [Bailey]. I’ve still got it framed. It’s hanging on the wall in front of me now.”

Hodgson is an LA-based designer. From 2004 to 2006 he was the president of AIGA Los Angeles.

Lawrence Grobel, Features contributor, 1977–87

“I got a call from Ira Ritter, Playgirl’s then-publisher, wanting me to do interviews for [them]. I was a bit reluctant at first, but he agreed to pay me $12,000 per year for three to four articles, written under a pseudonym. I’d asked for that, because I didn’t want [Playgirl] to interfere with my other work. I ended up using [multiple bylines], depending on the assignment: my real name for the Dolly Parton interview, and ‘Alex Michaels’ for Steve Martin, for example.

“Ira was quite the character. Soon after I [signed on], my doorbell rang. It was a guy in a chicken costume. He was holding balloons, and Ira’s signed contract, which he handed to me. I realised then that I was dealing with a different kind of [publisher]. Ira and I became good friends; he’d let me drive his Rolls-Royce.

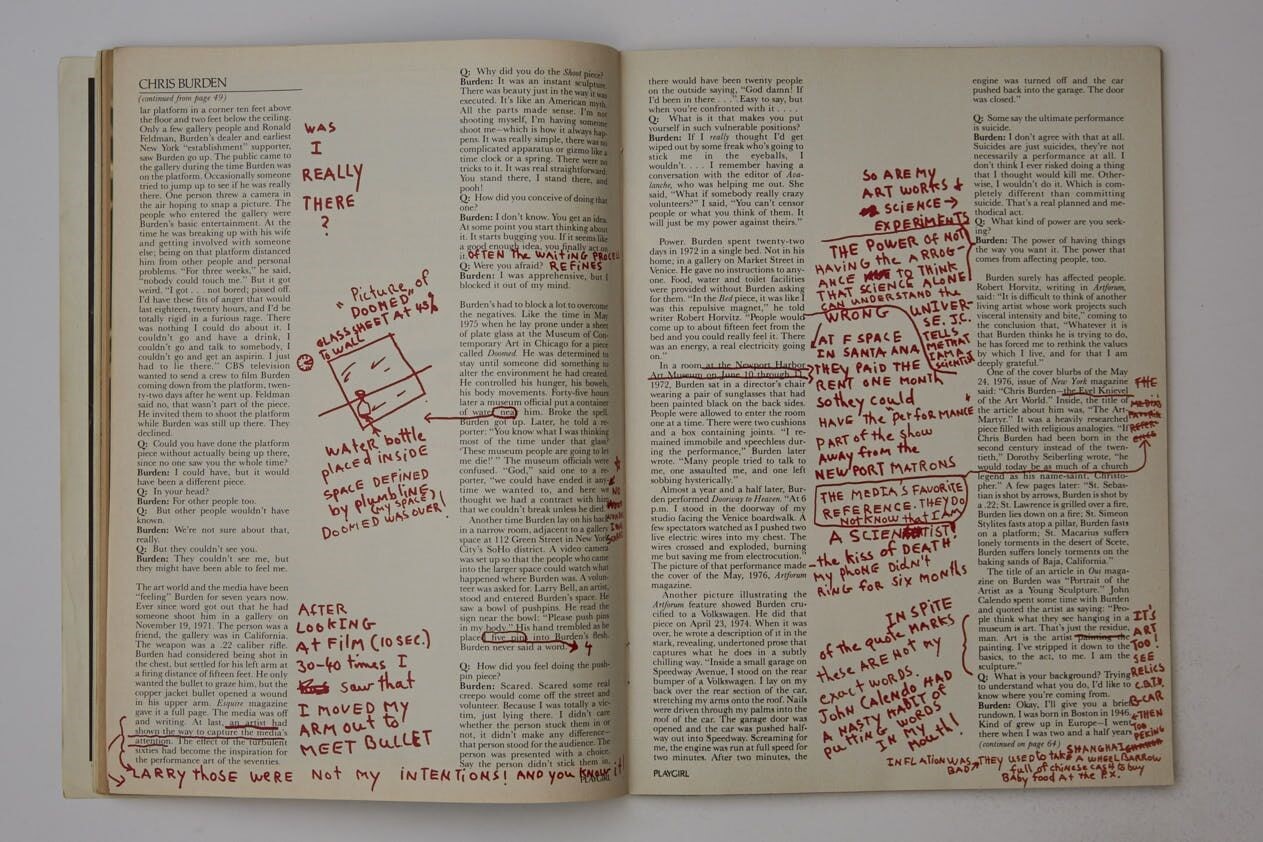

“I could never say no to Playgirl. I had a kind of freedom there. My most memorable [profile] was one of Chris Burden. In the late 70s, he was the hot, young artist – famous for crazy [stunts] like having his lawyer shoot him in the arm or crawling through broken glass. For one show, he framed all his press clips – these attempts by magazine writers to understand him. [Over the original text], he’d written his own comments in red. So I said, ‘Why don’t I write my own article on Burden, and invite him to the Playgirl offices before [it goes to press]? He can add whatever comments he wants, and then we’ll publish them in the actual piece.’

“This was a difficult thing for a magazine to agree to. But Ira said, ‘OK’. Burden agreed, too, and it was amazing; he came in and wrote on every page. As he read, he’d say things like, ‘Larry, that’s not my intention and you know it!’ After the piece was published, I asked the art director for the galleys, which I then framed. It’s a valuable piece of art now! And it was probably the first time that a subject’s feedback was included in the story itself. Which I think makes it one of the more accurate pieces ever written!”

Grobel is a writer and journalist, and the author of 28 books.

David Vance, Photographer, 1974–88

“My first assignment was shooting the ‘Men of Ft. Lauderdale’ pictorial in the mid-80s. It was a bunch of guys and was pretty tame – beach-oriented, as I recall. Playgirl was definitely bucking the norm, but I think they were conflicted about their market. They went back and forth with the frontal nudity. Celebrity shoots were generally more tame, and I shot centrefolds that were non-nude. But at one point they wanted full erections, which I was never quite comfortable with. It was awkward for me – addressing that with the models. They supposedly targeted a female audience, but I don’t think the majority of their subscribers were women. It was never polished enough for sophisticated women [nor] bold enough for their gay audience.

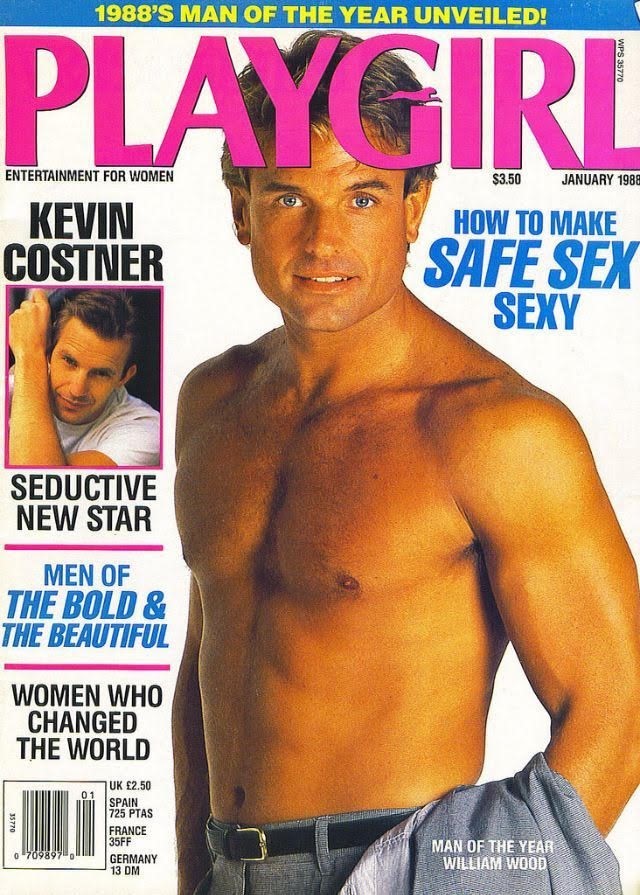

“My most memorable shoot was a cover [story] for the ‘Man of the Year issue’, in 1988 [featuring] William Wood. It was on location, at a house that they rented in Venice, California. We were on a deck overlooking mountains, with William standing in the doorway, when I heard the stylist suddenly scream, ‘EARTHQUAKE!’ I turned to look and saw that the landscape behind us was moving. It was my first earthquake! Quite a shocking and disturbing experience, but we finished the shoot nonetheless.”

Vance is a Miami-based photographer.

Karen E Bender, Author, former intern

“When I was 19, I wrote a short story about a young woman’s first sexual experience. My writing instructor at the time suggested I submit it to Playgirl, which I’d never heard of. But I thought, ‘Why not?’ Their fiction editor, Mary Ellen Strout, called me one night offering $500 for the story. This was a great amount in 1983, especially for me. When the issue came out, my family had to drive to the San Fernando Valley to find a copy. We bought about ten of them, and there was my story! Beside ads for dildos, amusingly. It was really one of the most thrilling moments of my life; I felt like I had arrived on the literary scene.

“Later, when I was at UCLA, I interned at Playgirl’s Santa Monica offices. Every so often, a muscled, nervous-looking man would pass through, and I’d think, ‘that’s a centrefold’. On the wall, they had a list of different terms for penises. Otherwise, the office wasn’t particularly risqué – mostly cubicles and people in suits. When I’d tell people I interned there, they would mostly laugh and ask what it was like. I didn’t know anyone who actually read the magazine.

“The senior editors were smart women in their thirties who viewed Playgirl as a feminist statement – a scrappy outlet for women claiming their sexuality. I wanted to be an investigative reporter, and one day, they asked me to write something. At the office, I’d come across these so-called educational videos for review – titles like The Guide to Oral Sex. They were essentially porn, but I had the idea to call some of the tapes’ producers and have them explain their educational value. The whole thing was absurd, but most of them were patient with me. Except for one unsavory guy, who responded to my questions by trying to intimidate me. When I told my editor, she explained he’d reacted that way because I was a woman asserting authority. Her encouragement was enough for me to finish the article ... Which I did!”

Bender is the author of four books, including the story collections The New Order, which was long-listed for the Story Prize, and Refund, a finalist for the National Book Award.