As a series of retrospective releases based on the renowned director’s career comes out, AnOther takes a close look at five of the best works by Shinya Tsukamoto

In 1989, Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: Iron Man came out of leftfield to win the best film award at FantaFestival in Rome, a watershed moment that permanently changed the fortunes of Japanese cinema thereafter. An avant-garde, black-and-white art film about a man who painfully turns into metal, it introduced the world to a new breed of highly creative Japanese filmmaking in the wake of one of the most barren decades in the history of Japanese cinema. With studios going bankrupt and audiences increasingly looking to foreign imports, Tetsuo suddenly declared a new beginning for the country’s entire film industry.

So closely is Tsukamoto tied to this moment that he is known almost exclusively for this single text. But Tsukamoto’s career flourished after Tetsuo, with a series of fiercely independent and controversial artistic works solidifying his reputation as one of Japan’s leading avant-garde filmmakers. He remains an enduring presence at international film festivals to this day, attending the screening of his most recent film Killing at Venice in 2018 before returning the following year as a member of the Jury. His status as a figure among the world’s elite filmmaking class, meanwhile, was cemented in 2016 when Martin Scorsese cast him in a pivotal acting role in his religious epic Silence.

Tsukamoto’s canon is uncompromisingly his own. A genuine auteur, he not only writes and directs his films but also produces, edits, and acts in them. He’s been applauded for his lively camerawork, provocative use of colour, dynamic editing techniques, and above all, for the rebellious and artistic spirit of his films. His films transcend conventional genre tropes, eschewing traditional narrative structures for deep symbolism. A meticulous perfectionist, he has been described as a “madman” by filmmaker friend Takashi Miike.

As film distributors Third Window Films and Arrow Video prepare a series of retrospective releases based on the renowned director’s career, AnOther takes a close look at five of the best works by Japan’s greatest cult filmmaker.

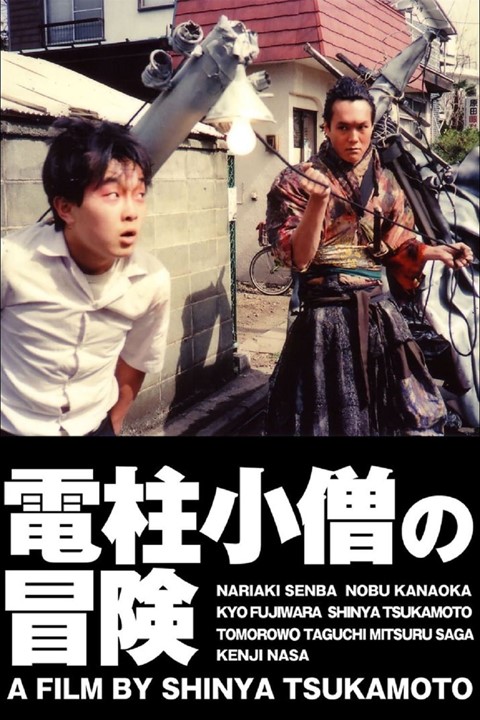

The Adventure of Denchu-Kozo, 1987 (lead image)

Originally a stage play, this extremely low-budget experimental 45-minute short was Tsukamoto’s final practice run before making the jump to feature-length filmmaking – and it’s a wild ride. A kaleidoscopic tale concerning a bullied schoolboy who travels through time to battle vampires in another dimension, this madcap 8mm short is notable for its remarkably ambitious art design and home-made special effects.

Spiritually of the same cloth as Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead and the early VHS films of Edgar Wright, Denchu-Kozo features stop-motion katana decapitations, Indiana Jones-style face-melting, and a monster inspired by the kaiju monster films of the director’s childhood. But to dismiss it as an over-imaginative exploitation film is to miss the point. Innovative animation techniques including Tsukamoto’s signature hyper-speed, live-action stop motion are seen in their earliest form here as metal wires squirm like catatonic snakes. The effect is striking, even on low-quality Super 8 film.

The film was selected to compete in Japan’s PIA Film Festival in 1988, where it won the Grand Prize – setting a precedent for the works that would follow.

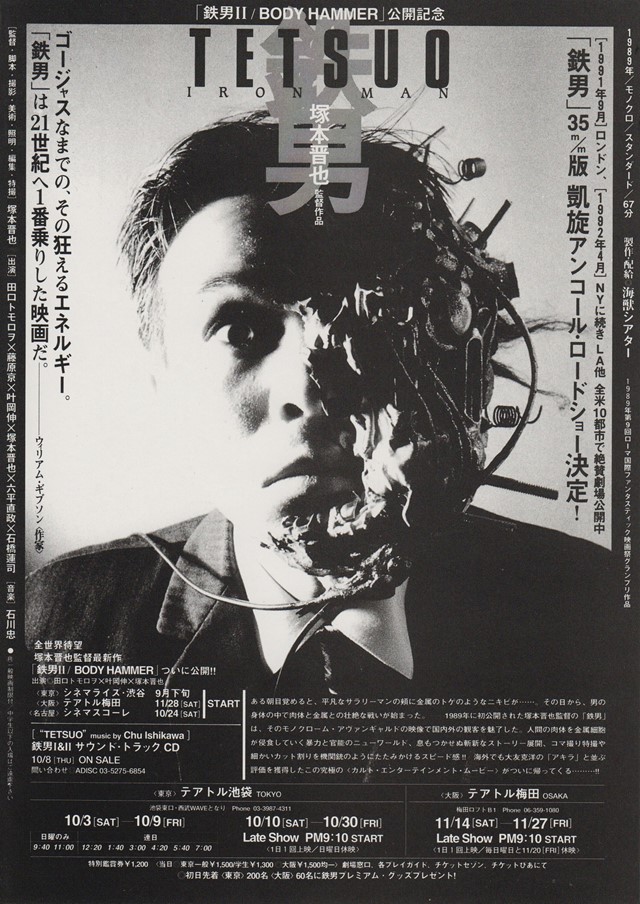

Tetsuo: The Iron Man, 1989

The influence and legacy of Japan’s definitive cyberpunk film cannot be understated, and its singular style is as exhilarating today as it was 30 years ago. A true marvel of surrealist cinema, its graphic imagery is indebted to Luis Buñuel as much as it is to David Cronenberg. The otherworldly atmosphere, dystopian setting and black-and-silver colour scheme, meanwhile, have drawn comparisons to the experimental early works of David Lynch.

The strange tale of an office worker who slowly transforms into metal has been interpreted as a comment on the negative consequences of Japan’s rapid industrialisation after World War Two, which culminated in a period of massive economic stagnation in the 90s. The film itself almost bankrupted its creator, after a gruelling 18-month filming schedule resulted in mass crew mutinies and enough stress to force the director to consider abandoning it altogether.

Set in a desolate Tokyo wasteland where piles of junkyard scrap take the place of trees and shrubbery, almost every aspect of the film’s design evokes metallic imagery. TV static, roaring trains and clinking kitchenware dominate the audio track, while the industrial rock score is built around the tireless chinks of beating iron. The hyperkinetic editing is jagged and violent, while spiky stop-motion sequences only accentuate the film’s unnerving atmosphere. It’s a brilliant, insane prospect of a film that remains as exhilarating today as it did 30 years ago.

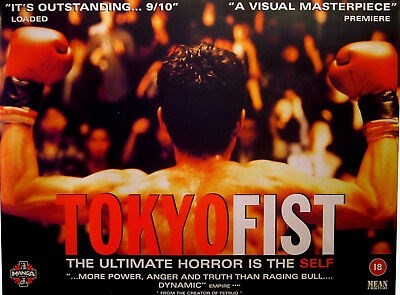

Tokyo Fist, 1995

Japan’s answer to Raging Bull forgoes the epic narrative of its American cousin in favour of super-stylised imagery and cryptic symbolism. It won the Grand Prize at the Tokyo offshoot of Sundance Film Festival, where it left a lingering impression through its expressionistic set pieces and thinly veiled social criticism.

The film stars both the director and his brother in leading roles, as opposing boxers (the former a diminutive office worker; the latter a hardened pro athlete) competing for the same woman. But the film subverts the machismo of typical sports dramas by painting each fighter as emotionally pathetic, while the female lead, Hizuru, is empowered by her dominance over them.

From the dynamic opening scene of a boxer unleashing a flurry of lightning-fast jabs at the camera, to the slow-mo sparring bouts soaked in foggy blue, yellow and red lights, the violence that dots this powerhouse film is expressionistic and vivid. Even the soundtrack, full of pounding tom drums, is based on the rhythmic thumps of a punching bag. But the message beneath it all is symptomatic of Tsukamoto's nihilistic view of society; in a comment on the unforgiving work culture of Japan, each combatant is left disfigured and humiliated, and there is no catharsis or triumph to their struggle.

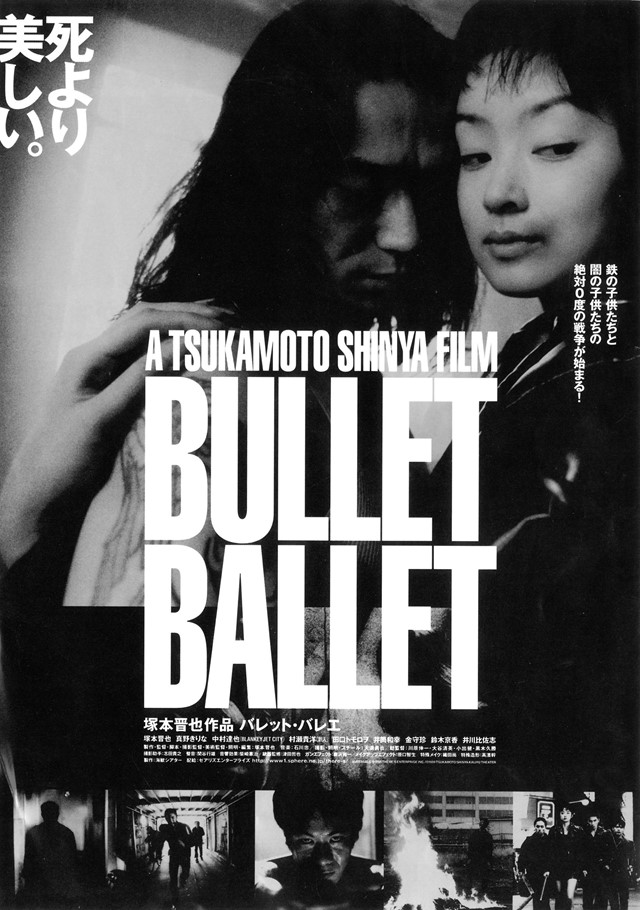

Bullet Ballet, 1998

If Tokyo Fist was Tsukamoto’s Raging Bull, then Bullet Ballet is his Taxi Driver. A rich, psychological film noir shot using Tsukamoto’s signature shaky-cam style, it follows grief-stricken salaryman Goda (played by the director himself) as he embarks on a search for meaning after his girlfriend’s unexpected suicide. Initially a misguided obsession with the weapon that took her life, Goda’s navigation of the labyrinthine criminal underworld of Tokyo in search of a gun soon becomes a moody and evocative journey into the psyches of its troubled young inhabitants.

A comment on the societal flaws of two separate generations – the morally abject, directionless youth and their monotonous, work-obsessed predecessors – the film was inspired by a real-life event in which Tsukamoto was robbed by a group of young people on his way to a train station. This theme of juvenile delinquency would end up dominating Japanese cinema in the late 90s, as the country saw a wave of crimes committed by young people as the country entered an economic recession.

The film premiered at Venice Film Festival in 1998, thereby becoming his first film to penetrate the golden standard of international film festivals. The subsequent bidding war for the rights to his films in France would open the gates for Canal+ to distribute his catalogue throughout mainland Europe for the first time.

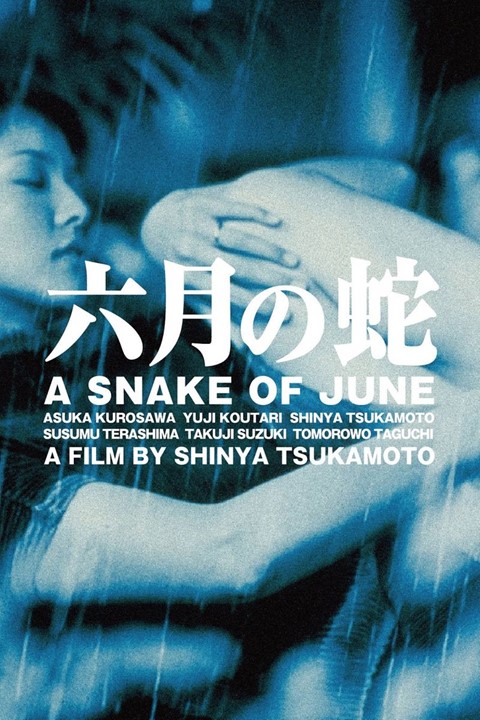

A Snake of June, 2002

Tetsuo was full of phallic imagery and sexual undertones, and Bullet Ballet was built around the fetishisation of a gun – but A Snake of June is the first Tsukamoto film that might be considered overtly erotic by nature. Influenced by the provocative photography of Robert Mapplethorpe and Helmut Newton, it is quite literally soaked with sexual imagery.

The film concerns Rinko, a demure and shy wife who is blackmailed after being filmed masturbating while her asexual husband is at work. But in an unexpected twist, this compelling story empowers the female lead by provoking a sexual liberation within her – subverting the traditional female roles established in the family dramas of classic Japanese directors like Yasujiro Ozu. It may be Tsukamoto’s most complete film to date, and, deservedly, it was awarded the Special Jury Prize at Venice in 2002.

A Snake of June’s stunning visual style is its greatest attribute. Filmed in black and white, but saturated with a vivid blue tint, the film is loaded with rich symbolism. It rains constantly in the anonymous Japanese metropolis where the film is set, and the exotic, monsoon-like downpour is a constant sexual presence. And while water, a symbol of femininity in Japan, is the film’s primary sensory metaphor, A Snake of June’s mystery-laden narrative and themes of voyeurism also lend it a powerfully noir-ish atmosphere.

Solid Metal Nightmares: The Films of Shinya Tsukamoto is released in the US by Arrow Video on May 26, 2020.