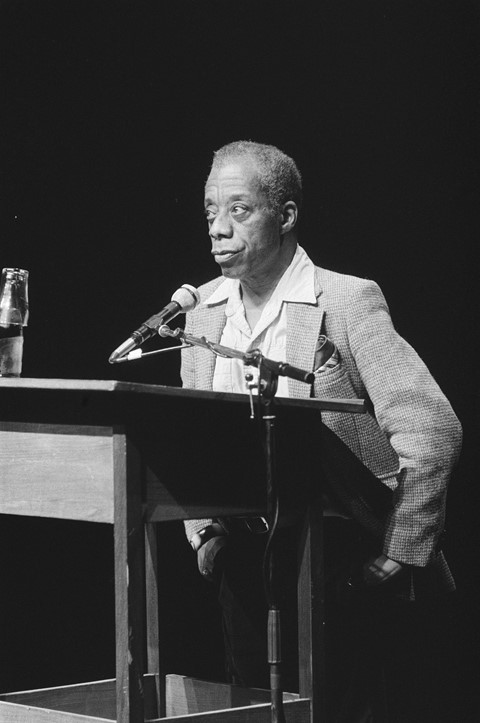

“Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise.” At a time for protest and introspection about each of our own racial biases, we look back to the searing words of black American author James Baldwin

The murder of black American George Floyd, at the hands of a white police officer, has become a catalyst for protest across America, and around the globe. But it has also served as a vital moment of contemplation and introspection, for asking ourselves the tough questions we often avoid: How does my own racial bias operate? How can I amplify black voices? How can I approach the micro and macro aggressions of racism in my workplace, my family, and on the street? Who does my own government work for and against? In answering these honestly – and many more questions like them – only then can we bring about tangible change in our own communities, wherever in the world that might be.

There have been many guiding voices for change in our current generation: from former AnOther cover star Indya Moore, whose Instagram has become a vital resource for protesters, as well as highlighting the white violence committed against the black queer and trans community, to the authors and writers Reni Eddo-Lodge, Ibram X Kendi and Ijeoma Oluo (our anti-racist resource contains more names to read and follow, which will be continually added to). But there are voices from previous generations which continue to resonate, from Angela Davis – whose voice, in a clip from The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975 on the necessity for revolutionary action, has been widely shared on social media – to James Baldwin, whose words seem more pertinent than ever.

Baldwin rose to prominence in mid-century America with a searing collection of essays on race in the country, Notes of a Native Son (1955). A landmark work, it tracked the injustices of his country on his own body and life – “[It] named for me the things you feel but couldn’t utter … articulated for the first time to white America what it meant to be American and a black American at the same time,” said the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. But Baldwin was just as masterful when it came to fiction, too: Go Tell It On the Mountain, a tale of an African American teenager growing up in the Harlem pentecostal church, and Giovanni’s Room, which explores a fated gay love affair in Paris, both remain classics of 20th-century literature.

The impact of Baldwin’s words is not easily described; it would take Toni Morrison, perhaps the greatest American writer of her own generation, to do so in a tribute to the writer she called ‘Jimmy’ after his death. “The difficulty is your life refuses summation – it always did – and invites contemplation instead,” she wrote. “I never heard a single command from you, yet the demands you made on me, the challenges you issued to me, were nevertheless unmistakable, even if unenforced: that I work and think at the top of my form, that I stand on moral ground but know that ground must be shored up by mercy, that ‘the world is before [me] and [I] need not take it or leave it as it was when [I] came in.’”

It is with this spirit that we have collated some of Baldwin’s most powerful words on race, white violence and activism. We encourage you to seek out his work further – a reading list is included below – as well as the many black voices which have been inspired by his words in his wake.

- “Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfilment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!”

- “Whatever white people do not know about Negroes reveals, precisely and inexorably, what they do not know about themselves.”

- “I don’t like people who like me because I’m a Negro; neither do I like people who find in the same accident grounds for contempt. I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticise her perpetually. I think all theories are suspect, that the finest principles may have to be modified, or may even be pulverised by the demands of life, and that one must find, therefore, one’s own moral centre and move through the world hoping that this centre will guide one aright. I consider that I have many responsibilities, but none greater than this: to last, as Hemingway says, and get my work done. I want to be an honest man and a good writer.”

- “I am what time, circumstance, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am, also, much more than that. So are we all.”

- “The question I’m trying to raise is a very serious question. The mass media – television and all the major news agencies – endlessly use that word ‘looter’ … On television you always see black hands reaching in, you know. And so the American public concludes that these savages are trying to steal everything from us. And no one has seriously tried to get where the trouble is. After all, you’re accusing a captive population who has been robbed of everything of looting. I think it’s obscene.”

- “The power of the white world is threatened whenever a black man refuses to accept the white world’s definitions.”

- “I imagine that one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with pain.”

- “If the American Negro, the American black man, is going to become a free person in this country, the people of this country have to give up something. If they don’t give it up, it will be taken from them.”

- “What one does realise is that when you try to stand up and look the world in the face like you had a right to be here, without knowing that this is the result of it, you have attacked the entire power structure of the Western world.”

- “Well, if one really wishes to know how justice is administered in a country, one does not question the policemen, the lawyers, the judges, or the protected members of the middle class. One goes to the unprotected – those, precisely, who need the law’s protection most! – and listens to their testimony. Ask any Mexican, any Puerto Rican, any black man, any poor person – ask the wretched how they fare in the halls of justice, and then you will know, not whether or not the country is just, but whether or not it has any love for justice, or any concept of it. It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.”

Further reading:

- Go Tell It on the Mountain

- Another Country

- Giovanni’s Room

- Notes of a Native Son

- The Fire Next Time

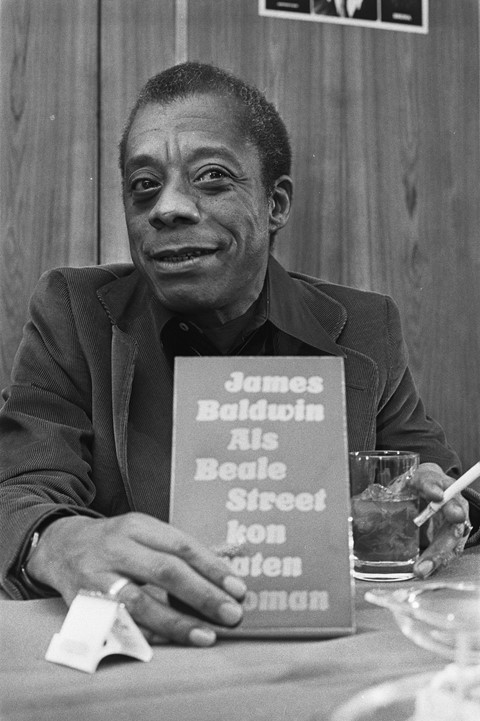

- If Beale Street Could Talk

- Letter from a Region in My Mind in the New Yorker (1962)

- How to Cool It, an interview with Esquire (1968)

- James Baldwin, His Life Remembered by Toni Morrison from the New York Times

- Watch I Am Not Your Negro, a 2016 documentary based on his unfinished manuscript, Remember This House