In the first instalment of a new column on PJ Harvey, tied to the re-release of her entire back catalogue, Jehnny Beth muses on the musician’s 1995 album To Bring You My Love

For this new, year-long series to mark the re-release of PJ Harvey’s entire back catalogue, AnOther invites friends and famous fans to write a column in response to a particular record. Edited by Claire Marie Healy, PJ Harvey: On the Record is a testament to the artist’s profound influence not just on music but on visual art, film, fashion and activism.

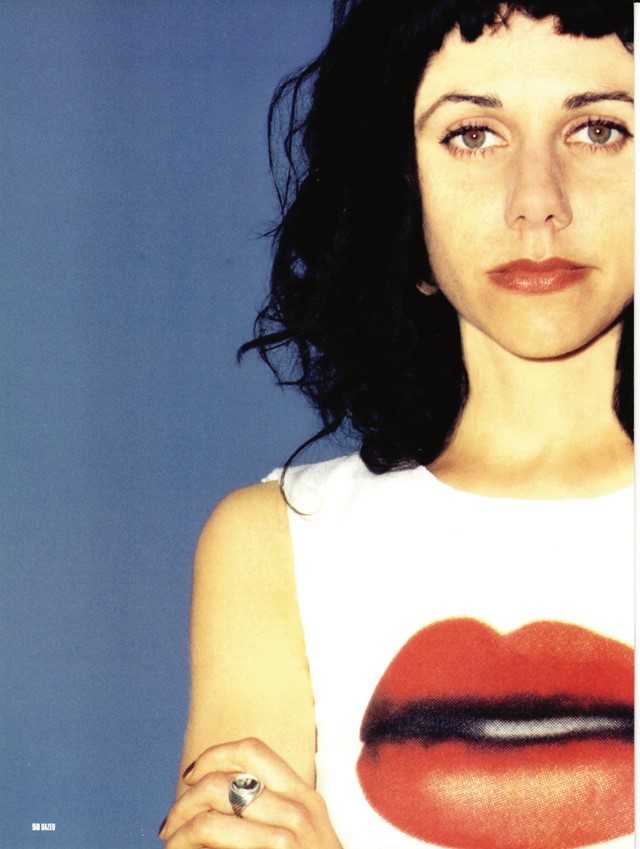

The first time I saw Polly was in 1998. She performed A Perfect Day Elise on prime-time French TV. She sat with her iconic black-and-white big lips T-shirt and shyly answered questions about her relationship with Nick Cave from an indelicate French journalist. The same week I bought Is This Desire?, quickly succeeded by To Bring You My Love, with its sleeve depicting Harvey drowning like Ophelia.

That’s when I heard the first lines: “I was born in the desert”. I was 15.

Everything she sung, I believed. As a teenager, heartbreaks were a kind of self-inflicted permanent condition and the album perfectly painted that agony in baroque red. The vibrato of her voice on the word ‘love’ at the end of the opening track is probably one of the artefacts of modern music that has influenced me the most – less because I failed to recreate its technique, more because I tried to relive its urgency. Furious and bereft, each song of TBYML reached inside of me to make its mark, like an enchantment. They seemed not only to understand the emergency of life but to be fuelled by it: making their way safely between the extremes, they became my war cry.

Fast forward years later in London, Polly shares her phone number after my performance with Savages at Ministry of Sound and invites me to give her a call at my convenience. From there sprang a friendship which the young teenager in me could have never anticipated. She relates her past experiences openly as well as her current research. As I get to know her better, I realise that her willingness to talk about herself is matched by the genuine humility with which she talks about her records. She wishes above all to be simple, absolutely simple (she still takes the bus everywhere she travels in London), and it is not the least of Polly’s contradictions that she is so profoundly simple and deeply complicated. She makes an effort to be clear and direct. Her manners are like her style of music – straightforward, channelling all kinds of hidden energies. She never talks about her work with self-importance, yet whether or not she wishes it, there is still, after years of knowing her, a tenacious and subtle mystery to ‘PJ Harvey’.

“One can expect at any point the most tremendous things from this dangerous character, that she will run amok and destroy the world, that she will drive mankind to frenzy and desperation, that she will never stop until she is reunited with her flesh-and-blood lover”

Any work of art begins in mystery, in the inexplicable. So much about TBYML still can’t be explained, which is probably one of its biggest legacies. At the time, the enigmatic aspect of the album worked perfectly against that part of me who wanted to explain and understand everything, the famous ‘French mentality’ which I had inherited, the legacy of Descartes and Voltaire, which thinks it can reduce the world to something that is completely intelligible. With TBYML, I enjoyed giving myself over to the irrational images that Polly was offering. André Breton once said about somebody, “He’s a jackass, he never dreams”. Polly made me dream: a pleasant dream, a soothing and dangerous dream.

From the self-metamorphosis characterised in her voice and her lyrics emanates the darkest aspects of the record. Already after three songs one has been in the presence of excessive madness and various lunatic and surreal states of being. One can expect at any point the most tremendous things from this dangerous character, that she will run amok and destroy the world, that she will drive mankind to frenzy and desperation, that she will never stop until she is reunited with her flesh-and-blood lover. Every lyric on the album comes with that same mythic weight, from a character who begs to God and gets no answer but keeps begging.

Because there is an underlying tension in this record: universal unrequited love, erupting as if from an ancient volcano. While Polly’s voice is free by nature, the character she sings about still sounds imprisoned like an animal in the zoo. Here is perhaps its biggest tragedy: that in the kingdom of TBYML there seems to be no room for any positive form of freedom – except in romantic death. Freedom isn’t palpable yet for it is only after man cries “God is dead” that he will be able to exclaim: “I can see”.

If Polly has evolved as an artist since TBYML, and if the records she has made after did not attempt to reflect its dark and mysterious style faithfully (she never stays long with one sound or persona), this same passionate taste for the irrational is still very much a part of her. I have never understood – and hopefully I shall be lucky enough never to understand – why her childish voice in Let England Shake, or her shout in This is Love move me so deeply. However, her ability to adopt a new character at each record is not to say that Polly isn’t conscious of her own power and doesn’t know how to recreate it. Above all, beyond all her many successes, commercial and artistic, she has always stood aloof from the fashion of the day, and firmly insisted on being herself – this, the final mark of artistic originality.

Jehnny Beth is a musician who released her debut solo album in June

PJ Harvey’s reissue of To Bring You My Love and To Bring You My Love – Demos is out today