Lynne Tillman talks to Holly Connolly about her book Men and Apparitions, which explores the effect of the women’s movement on men, as well as how she came to be a writer and the value of fiction

There are two qualities, I think, that are important to mention straightaway about Lynne Tillman, in part because they are so disarming in a distinguished cultural critic, novelist and New York institution. The first is that Tillman is very funny, with a self-deprecating wit that she aptly calls “gallows humour”. She is also uncommonly inquisitive, especially by the standards of an interview subject, with a habit of turning your question back over to you.

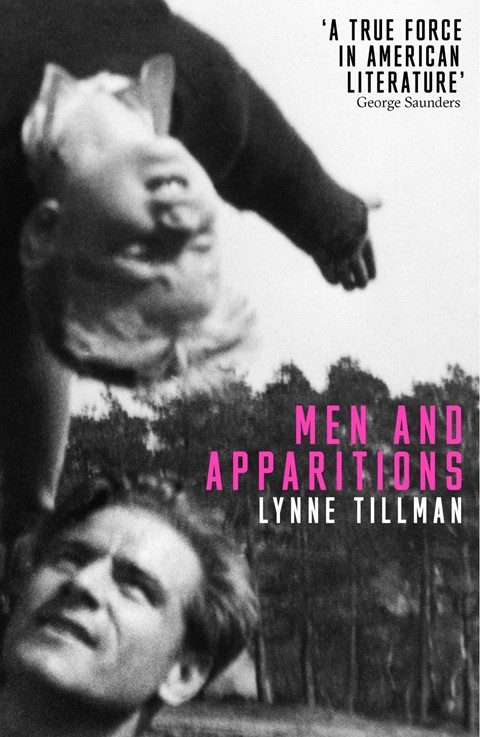

We speak over the phone on the day of the US election, to discuss Tillman’s novel Men and Apparitions. Published in the US in 2018, and brought out in the UK this month by Peninsula Press, it’s the first of her books to be published here since the early 2000s, and her first novel in 12 years. (Though she brought out several books and taught too, in the interim. “Was it 12 years?” she says. “Well believe me, I wasn’t idle.”) The author of 15 books in total, since the late 80s Tillman has been a prolific and original writer of both fiction and criticism. Her 2014 collection of essays What Would Lynne Tillman Do, 2006 novel American Genius: A Comedy, and recent work for Frieze in particular have brought her work to the attention of new generations of readers.

Initially conceived as a story about living in a glut of images, Men and Apparitions centres around 38-year-old visual culture anthropologist Ezekiel ‘Zeke’ Hooper Stark as he interrogates his history, practice, and the breakdown of his marriage. “He’s self-conscious, and like many self-conscious people he doesn’t know himself,” says Tillman. “In America people are teenagers when they’re 38 still.” Interwoven with meditations, or mini-essays, on the meaning of photography and images, the novel is a deft consideration of intimacy, self and gender, in particular contemporary masculinity. Arguably ethnographic in parts itself, Men and Apparitions concludes with a field study, ‘Men in Quotes’, with answers lifted directly from a real survey that Tillman sent out to roughly 40 of her male acquaintances.

Holly Connolly: When I spoke to your publisher he pointed out how much affection there is for you in the States. He said something that I loved, which was that one American bookseller had told him, “Everyone has a Lynne Tillman story.”

Lynne Tillman: Everyone has a story? Well I’d like to hear them! You should ask him if he remembers any of the stories, I hope they’re salacious!

HC: Part of the novel is set in London, and it’s a section that reads very authentically. You lived in London and Europe for a time, right?

L: London is very important to me. I was there in my twenties for quite a while and it’s where I began to kind of take myself apart and put myself back together differently. Amsterdam also, I was going back and forth between the two and coming to terms with the fact that if I thought I could be this ‘great writer’ then I’d better get started. And I couldn’t do it in Europe, somehow, it was a language issue in part. I was hearing English spoken by the English, and it’s a very different language in a way. So I was really not getting it together in Europe, while so many other American writers found it to be the place that they could write, I found it to be the place I couldn’t write. I needed to come back and take very seriously what I had to do. So that’s what I did.

HC: What did taking it seriously look like?

LT: When I would have an idea to do something, I finished it. I didn’t just start something and let it fizzle away. I sat down, said, “I’m going to write this,” and I did it. The difference between wanting to be a writer and actually writing is a world apart, and the determination to do it, and then executing that, took everything I had in me. Part of me, psychologically, was so terrified, so insecure, and it’s odd, because at the same time I had this other idea that I could be a great writer. Talk about a contradictory psyche! But one of them was stronger than the other, so it won out; the idea that I had to write.

HC: I thought a male protagonist was an interesting way of exploring how feminism has affected men; how it’s shaped them and how the male role fits around feminism too. There’s a kind of question mark hanging over a lot of Zeke’s identity.

LT: As far as I knew, writers hadn’t really taken up this idea of the effect of the women’s movement on men. And I think it’s been enormous, and in a funny way it may have been more enormous in some ways than on women. The changes that you see, and I’m not saying across the board and that there aren’t some neanderthals walking around, but I was very interested in all my younger male friends, gay and straight, who had very different ideas and were struggling with how to make these changes, and how to deal with their sexuality. And I think that the movement against gender conformity is very, very important, and it comes out of what feminism and the women’s movement set up.

HC: This might seem very specific to you, but it’s interesting to me from a UK perspective as feminism here has seen this very strange turn, with a very small but vocal minority of ‘feminists’ adopting a trans-exclusionary stance. Given that this hasn’t been the case in the US, I wanted to know if you had any thoughts on this, as an American who is engaging with the impact of feminism.

LT: I think it was a friend of mine, Tom Keenan, who is a brilliant theorist, who said that people don’t want to give up. In order for somebody else’s rights to be furthered, in a way you have to give up your own position. And I understand their resistance, because I think they’re hanging on to something; it’s been very painful for many feminists, or for women who call themselves feminists, to be able to speak about their oppression as women. But I don’t agree with this position, because I’m not an essentialist, and I do think that what we call a woman is a constructed thing. People are afraid of change. But I think history is on the side of the trans community, because I think they’re part of a wave coming out of feminism that is challenging the meaning of the body, what the body stands for, and because you’re in this body how it’s supposed to act and what it’s supposed to look like. It’s this great challenge to the idea that the body is the foundation of everything.

HC: You’re as much a writer of cultural criticism as you are of fiction. In this case, did you feel the novel gave you the freedom to explore certain ideas and concepts that a medium like journalism might not allow for?

LT: I think fiction is as true as any other form of art. I can use characters to be and do and show the consciousness of a period, and have them completely involved in the world outside them, and it affects them of course, both consciously and unconsciously. Writing a character gives me a chance to explore things that I think about, or don’t think about, or think that others think about. I don’t have to agree with everything, I’m creating something other than myself. I think fiction is incredibly important, because without it we can’t think our way through or past a present that may be awful.

The problem with journalism, sometimes, is that it wants to speak about groups of people, and the notion that there are individuals inside, who make up all of these groups, and they have differences from each other, gets lost. I mean I don’t want to speak of the best journalism, but I think that’s a problem in most journalism.

Men and Apparitions by Lynne Tillman is published by Peninsula Press.