In April 1977, Playgirl was at the height of its powers. It had been launched just four years earlier and was reportedly selling around 1.5 million copies per issue to its largely female (and gay male) readership. It had cemented itself as a publication of the sexual revolution, complicatedly helmed by male publishers and welcomed by some – not all – feminist thinkers. The cover that month prominently featured a woman’s cherry-lipped, sunglasses-obscured face, as well as the reflection in her lenses: caught in her line of sight was the naked torso of a prone man, magnified and doubled in her oversized frames.

The magazine is, for the first time in a while, getting the relaunch treatment. The first issue of its new iteration hit newsstands last month, under the guidance of editor-in-chief Skye Parrott (formerly of Dossier). Parrott sought to revitalise some of what the magazine was aiming for in its heyday: to be a feminist response to Playboy (the magazines have no relationship. According to the New York Times, Playboy actually sued over trademark infringement in ’73, before settling). Early Playgirl was unapologetically sexual – is still, perhaps, best remembered for its pensises – and was, simultaneously, less editorially extreme, interested in mixing lifestyle, culture, and politics right in with the sex. Take that April ’77 cover, which promises both an interview with Nick Nolte about his sex life and a reported feature on how terror cells become armed.

Playgirl changed hands a bunch of times; it eventually devolved into porn without the benefit of politics, before fading altogether. But in those early days, Margaret Atwood and Maya Angelou were writing for Playgirl. There were essays on reproductive choice appearing in its pages. It wasn’t perfect – it may, as Parrott suggested to me, have subscribed to a framework that simply placed women in male roles, essentially flipping which side of the sunglasses they were on – but there was a fascinating prospect underlying the enterprise. Perhaps a women’s magazine could encapsulate radical balance, could provide content that was both fearlessly steamy and smart. Maybe that’s a suggestion about what women’s lives are allowed to consist of.

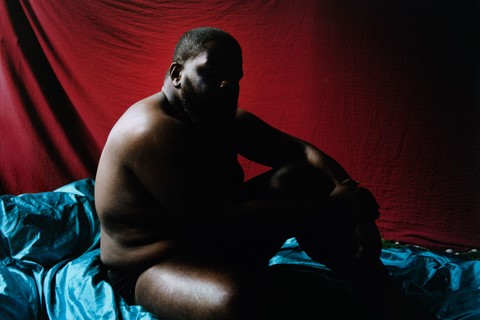

So relaunching Playgirl was, for Parrott, an opportunity to get in touch with these initial intentions, and to push them further. The new issue is bright, sleek, and bookish; at 270 pages, it feels more akin to coffee table décor than to slim monthlies. Its coverage includes the diversity of bodies now populating the modeling industry; indigineous women artisans in Chiapas, Mexico; Chloë Sevigny’s pregnancy at age 45. It has personal essays and a ‘Playgirl’s Heroes’ portfolio – ten mini-profiles of women making radical change in their communities. And it has a centrefold, an artful multi-page spread of posed, nude male bodies. It’s still Playgirl.

I called Parrott to talk about Playgirl’s uneven history, its revivication, and what reimagining this magazine means in 2020. Our conversation is condensed below.

Amanda Feinman: I want to start by asking about your own personal history with Playgirl. What were your interactions with the brand before you came on board?

Skye Parrott: Before coming on board, I didn’t have any interactions with the brand! My ideas of what the brand were were really formed around what it was in its last incarnation – which was a gay porn mag. I went into my first meeting with the publisher [without] an understanding that what we would turn it into was actually a reimagining of the original DNA.

When it launched in ’73 it was really pushing the envelope, in terms of the content it was doing. It was quite smart, and had a really high level of contributors. And then it was sold, and became a lite version of that – like a typical women’s magazine, with naked guys added in. And then it was sold again. And that started this long, slow decline into something really different, where it really was just a porn magazine.

AF: There’s this interesting parallel between the history of Playgirl you’ve just outlined and the history of late 20th-century feminism. The magazine came about in the height of the second wave, and then encountered serious second-wave backlash.

SP: I think that’s such an astute point of view. When you think about how much time has passed ... the place that women still occupy in the world and the relationships between men and women ... when they launched this in the 70s, I really, really doubt that they thought that almost 50 years later, we’d be here having these conversations.

A thing that felt like it really deserved a reimagining ... in the ’70s, it felt like they had taken Playboy and just, like, shifted the paradigm. They had just stuck naked dudes in, instead of naked women. It was exciting to think about, well, what is a feminist publication actually here to do? Not just stick women in men’s roles, but really think about things through a feminine lens, right? Hopefully, you can look at this relaunch – if you want to line it up with the conversation around feminism – as a moment when that conversation is coming to the forefront again.

AF: To jump into the relaunch: how would you describe your editorial vision for Playgirl in 2020?

SP: Even though this is a magazine – historically, and in name – I really wanted to approach it more like a book or an object ... something [with] a life beyond the typical magazine cycle. The vision for it has to be broad. What are the conversations that are timely in this moment, that might help us move constructively beyond this moment? My team and I settled on the idea that Playgirl could offer all of that, through a feminine lens.

What that meant, practically speaking, was looking at what the strengths of femininity are, and how to weave those through the publication in a way that celebrates them. The ‘Heroes’ portfolio – which, for me, is really the heart of the issue – is looking at these women who are doing this incredible activism work using very feminine strengths, like community organising. The piece that we did about Chiapas, Mexico ... that’s really a celebration of how traditionally feminine crafts and skills can be used to lift up communities, in a way that’s sustainable. For me, that kind of thinking is spot-on.

“The magazine is about the layers of human lives, through this lens that’s feminine” – Skye Parrott

AF: You’re talking about highlighting the strengths of femininity ... something I think of, when I think of the strengths of femininity, is balance. And that feels like it’s happening on a meta level in the issue. There’s personal lives, politics, sex – which some people may think of as the bread-and-butter of the brand – but it’s all being held with equal weight.

SP: I think that’s exactly right. You know, I can’t tell you how many pitches I got that were just sex and vibrators. Those are absolutely things that have a place in the magazine, but for me, the magazine is not about that. The magazine is about the layers of human lives, through this lens that’s feminine.

AF: I do feel like, even as we talk about balance, we should also talk about sex and nudity! Probably the most iconic thing from Playgirls’s history is its centrefolds. I’m curious about your approach.

SP: Sex and nudity were always going to be a piece of this publication. The human body is a huge piece of the human experience – so looking at the body, for a magazine like Playgirl, there was no question. And the centrefold was too iconic not to reimagine! [We worked] with a female artist who is looking at the male body a lot in her work right now. She looked at male bodies of different shapes and kinds, different races ... some of [the images] look like they could come from an earlier Playgirl, but there are very different kinds of bodies in there, [with] an approach of the female gaze. In our actual fold-out, there’s two erect penises, and I think there’s a real humor in that. We had to nod to the history. And that’s also why the centrefold comes quite early in the magazine – it’s like, people are here for this. Okay, here you go! Here’s your penises! Now that that’s out of the way, here’s all the rest.

Also, from the beginning, it was clear that we were not just going to feature male nudity, because that really does not feel like a modern take on looking at the body. There’s probably more female nudity in the magazine than male nudity, ultimately.

AF: There’s also female nudity on the cover – which is not something, to my knowledge, that was done in the early days of Playgirl.

SP: No! From the beginning, we were clear that we wanted the cover to be a woman, and that we wanted it to look at female strength. In early conversations, we were thinking, maybe that’s an athlete. Then the opportunity to photograph Chloë [Sevigny] pregnant presented itself, and it seemed like such an incredible fit. First of all, she’s 45 years old, eight months pregnant. She’s photographed there in a way that you’re not used to seeing her – quite pared down. There’s this vulnerability of being a pregnant woman naked, and that also has this feminine power. I think there’s a subversion in that, power rather than sexuality.

AF: I want to ask about target audience, because Playgirl has historically mattered deeply to gay men and others who are non-women. I’m curious how you’ve thought about readership?

SP: Ultimately, the focus of the magazine is feminine, but the space is for anyone who’s interested in a different point of view on the world. I think that there are a lot of people who don’t identify as female who may be very interested in shifting the paradigm – how we talk about gender and power.

“Politics are not just one thing to throw in, among astrology and how to make your bedroom look cute. This conversation is a political conversation” – Skye Parrott

AF: It’s striking me that there’s something unique about a publication with a feminine lens, as you’ve put it. It’s not necessarily engaging explicitly or only with feminist politics.

SP: That’s an exact distinction that we settled on. And one of the huge differences between Playgirl as it started and Playgirl as it is now is that “the political” is [now] central ... to quote T Cole Rachel, politics are not just one thing to throw in, among astrology and how to make your bedroom look cute. This conversation is a political conversation, because you’re talking about who has power, who has a voice, who is being celebrated and elevated – in everything, from the essays to the pictures to who’s naked.

AF: Finally, I want to ask about your editor’s letter at the front of the issue. In it, you write that your goal “is not to put women in the same playing field as men,” – in contrast to Playgirl in the ’70s – “but to stake a claim for a new playing field.” Can you expand? What do you hope that editorial playing field will look like?

SP: I think it’s fair to say there’s a lot of exhaustion in the world – with the way the world is functioning, has functioned. And I think there’s a real hunger, right now, for reexamining questions of power and dynamic. What kinds of people are photographed in magazines? What do they look like, what do their bodies look like? Is there diversity in the kinds of people we’re celebrating or considering beautiful? And to circle back around that ‘Heroes’ portfolio – what are people doing with their lives to make them deserving of this kind of attention? I hope the magazine provides a different perspective on what deserves to be elevated ... at its very best, what Playgirl might offer is a different template, a different lens that you could look at the world through, if you’re interested.

Buy a copy of Playgirl here.