For many, to read the works of André Aciman, is to feel seen. To feel understood. The author’s books – which include Eight White Nights, Out of Egypt, False Papers, Alibis, Harvard Square, and perhaps most famously, Call Me By Your Name – are centred around inner life; the thoughts behind our words and deeds, more than our words and deeds themselves. In beautiful and highly polished prose, his writing articulates things that many of us have experienced but never been able to articulate ourselves, exploring themes such as attraction, obsession, fascination, desire, passion, and intimacy. His words often cut to the heart, speaking universal truths which transcend both time and place.

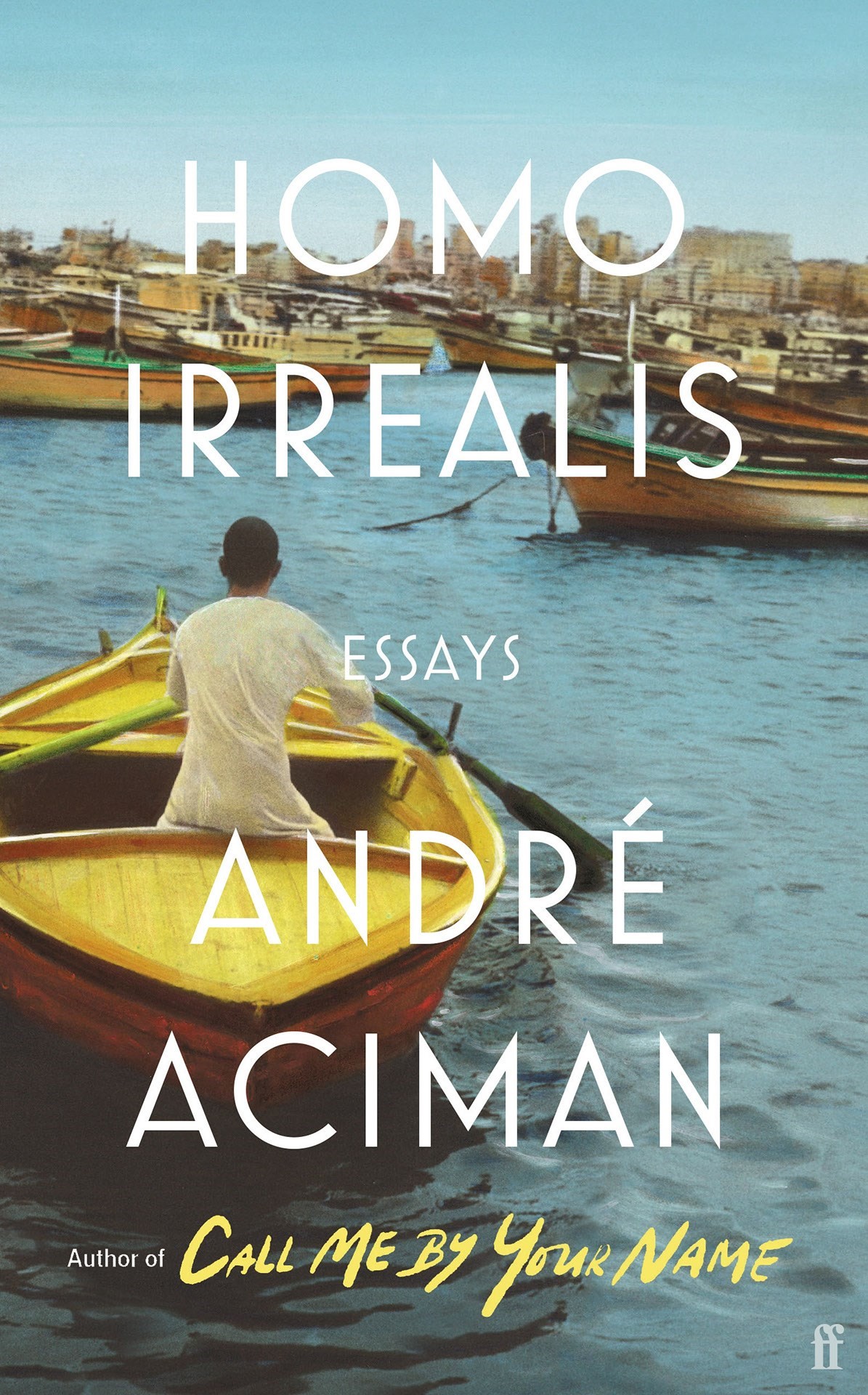

Aciman’s new book Homo Irrealis, published by Faber, is no exception. A collection of essays as opposed to a novel, the publication explores the ways in which the imagination can shape our memories or, as Aciman explains, “the ‘might have been’ that should have occurred in the past but never did, but continues to exist in us as if it had happened and we live with that”. Looking at the lives and work of figures such as Sigmund Freud, Constantine Cavafy, W. G. Sebald, John Sloan, Éric Rohmer, Marcel Proust, and Fernando Pessoa, Aciman mediates on time and the creative mind. But the goal is just the same as his other books: for readers to take his words and apply them to themselves.

Here, Aciman discusses this publication, the concept of homo irrealis and the reason he writes, as well as sharing some advice for aspiring authors.

TS: Could you explain to us the concept of Homo Irrealis and how you would introduce that to your readers?

AA: In French, there’s something called the imperfect tense, which is something that happened in the past but is ongoing. Then there’s something called the conditional mode which is something that might occur in the future. What is ironic is that both have almost the same exact spelling. There is a subliminal relationship between the two and I was always interested in that until I realised what really interested me is this moment in life when we are thinking not just of what might be or what we want to be or might have been but the might have been that should have occurred in the past but never did, but continues to exist in us as if it had happened and we live with that … This is true of everybody … [It’s] a domain in which we all live. I wanted to give it my best shot and the only way to do that was to use other people and to misread them in order to [bring] out this particular dimension.

TS: The book feels very personal, in the way that you open up about your thoughts and about your memories and your reflections on your memories. Do you feel like this is your most personal book yet? And how did you feel about opening up about these things, did you have any reservations?

AA: No, I try not to have reservations, among other reasons because I’m old enough not to have reservations. But also particularly when you write about desire, fugitive desire, you want to be as honest as you can be. I tend to have a very polished style but that doesn’t mean that I’m florid, I’m extremely bold. People write to me all the time telling me that I have written their lives, outed their inner selves. The reason [for this] is very simple: when I write about myself, I do so thinking that what I’m saying is true for everyone else. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have the boldness to do it. Call Me By Your Name, Find Me and even this book have moments that are extremely personal and it’s ironic that people identify with them but that’s the way I write. I share what I think you need to hear.

“Call Me By Your Name, Find Me and even this book have moments that are extremely personal and it’s ironic that people identify with them but that’s the way I write. I share what I think you need to hear – André Aciman

TS: That’s my favourite thing about your writing, and something I wanted to say to you, that in Call Me By Your Name, Find Me, and this book, you articulate things that I have thought and felt but never been able to articulate myself. In reading your books, I have felt amazingly understood and somehow less alone.

AA: People write to me every single day and confide things to me that they haven’t confided to their friends or relatives, or even to the people they are in bed with, partners with or married to. They tell me things about themselves and basically I am doing the thinking for the things that you have always considered but never quite focused on. I say nothing that is new to you, except that you’ve never quite focused on them. That’s my job, to say things that I know you’ve experienced. I get mail from women who are in their 80s and girls who are 13, 14 years old about Call Me By Your Name, telling me that I’ve written about their lives. Now clearly that’s not quite possible. All that I want to do is to help you ... the way I write is basically an invitation for you to borrow my words and steal them if you need to and apply them to yourself.

TS: One of the things you open up about in this book is your childhood in Alexandria and Paris. How has your upbringing has shaped you, and your writing?

AA: It has taught me one thing in particular, because I was being displaced, I felt that I was never in the here and now. I was never in one place, I was never a citizen of the place where I was. I lived in Italy, Egypt, France, I live in the US and I never quite felt that they were really my home. In other words, I always feel rootless. This rootlessness also has affected my writing in the sense that I’m not writing as a person writing in 2021, I’m writing like someone who could have been living in 1859 or in 2022, I’m sort of all over the place. I don’t want to root myself in the here and now. I watched the inauguration and they had all these contemporary singers and people that I’ve never heard of and frankly I would have appreciated some classical music too, because that’s where my heart is. But classical in the sense that it’s out of time, not rooted in any spot, any country, any moment, it’s just beyond time. That’s where I feel comfortable and that’s how I write.

TS: Perhaps that’s why your stories resonate with so many different kinds of people, because they transcend a specific time and place.

AA: I try, I mean it’s what interests me. I invent a house in Italy, I invent a profession that I know something about but not much, and I want to focus on what happens on the balcony between two bedrooms. Those two bedrooms could be in Guam, New York or Italy, it doesn’t matter. And people always say that I provide postcard views of the world, of Italy, that Italy is always in my heart. In Call Me By Your Name, I hardly describe anything Italian. I give you the smell of coffee, the smell of rosemary and the smell of lavender and I tell you there’s a beach nearby. It’s hot, so when you sit down on a chair, your thighs are burning, OK? That’s all I give you, I don’t give you much. But people feel that they bring their image of Italy to my prose which is a luxury to me, because I have no patience to describe it, I never describe a face, I don’t even give you their names until I really have to. All these things are incidentals to me because I’m really writing about what goes on in your head, in your heart and I love that.

TS: You also talk about your nostalgia for Alexandria in this book, and the idea of nostalgia for what never happened – which feels really relevant to this moment in history. Particularly in the US and the UK, where people seem to be longing to return to a time and version of their countries that never existed – a feeling that has fueled political events of the last five years. What are your thoughts on this?

AA: I stopped watching a lot of English shows for many years because I always had a feeling that it was more or less a Laura Ashley universe. It’s like Downton Abbey, did that ever exist? It’s a whole universe of nostalgia. It gives you a picture of an England that we all think existed but never did, which is fine. That’s what art does, it basically camouflages reality but on the other hand, it has also provided us with an escapist vision. In many respects, nostalgia is embedded in us, we want the past. We don’t necessarily want the real past, we want the one that has been arranged for us and lifted up.

TS: What do you hope people take away from this book?

AA: I hope they understand their own lives. I hope they’re honest enough to understand that this is about their lives not about mine. I want them to borrow everything I’ve touched on and say, ‘My god, the Irrealis mood is something I’ve been living with but never knew what to call it.’ When you speak about the might have been, what never was but could still be, though we fear it might happen but long it could – I say the sentence very fast because by now I know it by heart – but basically if everybody applied it to themselves they’d see oh my god, that’s true for me, that’s where I’ve been all my life and I hope they take away that. At the same time, it’s not for everybody. There are people who are staunch believers in living in the present and I envy them because I’m not that way and wouldn’t want to be either.

“ ... I’m really writing about what goes on in your head, in your heart and I love that” – André Aciman

TS: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers, especially those who may be struggling with writer’s block at the moment?

AA: Many people are blocked because they don’t know where to go with the story. That’s because the story is not about them. I always tell people, look into yourself and look into the person you were at the age of seven. You haven’t changed since the age of seven, none of us have. That’s where you will find all the material that you will need for the rest of your life. In the child of seven who is usually hurting in one way or another because he’s been bullied, abused, this or that. And he has insights into people, himself that we’ve chosen to ignore but they are there and very important.

One of the things I also tell people is to stop reading modern prose, stop reading contemporary writers, because you’ll end up sounding like them. Read the greats of the English language, the really great stylists, and learn what their trick was. Sometimes I even tell people to walk in their shoes, in other words, to parody them. Use their styles, try to imitate them, get out of yourself and out of your 2021 personality and adopt someone else’s.

TS: Who are those writers for you?

AA: One of them of course has been Proust. In the English language, I’ve always had a passion for Jane Austen. I thought she was brilliant. Edith Wharton is also brilliant. I’ve always liked women writers better actually. Katherine Mansfield was a particular person that influenced me enormously and I would never have been able to have written Out of Egypt if I hadn’t read Natalia Ginsburg. My favourite is Dostoevsky, but above all it’s Thucydides. The Peloponnesian War is a book that exposes human stupidity in the most ruthless manner. I love that, I love people who write about motives as opposed to actions. I encourage my students to familiarise themselves with what goes on in their heads, as opposed to what happens in their plots.

TS: That’s what I thought was so amazing about Call Me By Your Name because it’s almost about what goes on in Elio’s head, as opposed to what actually happens.

AA: This is where we live. When you think about a passion you’ve had for someone, which was obsessive and maybe even forbidden or shameful – I think desire is always a shameful proposition – we are always embarrassed about what we feel and when there is no way to communicate it, you are like a bottle of champagne that’s corked and building tension. I love that tension because I know it very well, I’ve experienced it many times in my life. I think most people have. As I always say, everything I write is written under the assumption that it is true for you as well.

Homo Irrealis by André Aciman is published by Faber.