James Balmont unpacks five of the director’s early productions, which tell a story themselves of how South Korea’s film industry became global phenomenon

It’s been almost a year since Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite staked its claim in the history books as the first South Korean film to win an Academy Award. And while no-one can deny that director Bong was deserving of the plaudits, many commentators were surprised it hadn’t happened sooner. This watershed moment marked the zenith of a film industry that had been on the rise for over two decades – but in the eyes of many, Park Chan-wook should have already put the cherry on the cake.

Heads were scratched in 2016 when The Handmaiden, Park’s erotic and Hitchcockian tale of deceit at the manor of a wealthy heiress in the 1930s, was snubbed by the Korean Film Council for submission to the Oscars. Despite winning a BAFTA for Best Film Not in the English Language in the UK, and being nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes, The Handmaiden was left wanting come January 2017.

It seemed like a major slight considering the work director Park had done prior in bringing South Korean cinema to the international stage. Who can forget the titanic global impact of stylish revenge thriller Oldboy – itself a Grand Jury Prize winner at Cannes in 2004? Or Korean vampire thriller Thirst, another Palme d’Or nominee? Park even found himself directing actors like Florence Pugh and Michael Shannon in the BBC TV series The Little Drummer Girl, in 2018; his influence and legacy around “Hallyuwood” is undeniable.

As South Korean cinema completes its lap of honour in 2020, and with production for Park’s forthcoming murder mystery Decision to Leave now underway, AnOther goes back to the early days of the director who arguably defined its ascendency better than anyone. Before global smashes like the ‘Vengeance trilogy’, The Handmaiden, and even the mid-00s hits of a certain Bong Joon-ho had captured the imaginations across the world, these early productions tell a story themselves of how South Korea’s film industry became a global phenomenon.

If you want to know how a story like Parasite came to unfold, there’s no better place to look.

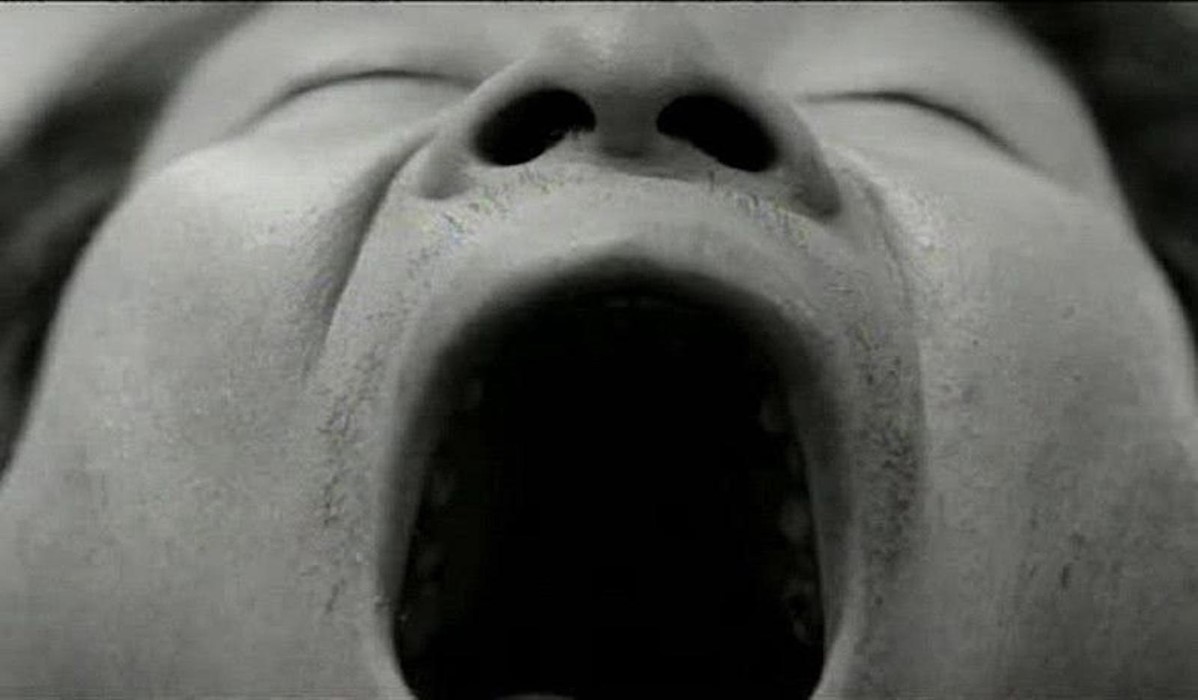

The Moon Is … The Sun’s Dream, 1992 (lead image)

Park Chan-wook’s career didn’t start with a bang. But it’s also fair to say that South Korea of the early 90s was quite a different place to the home of BTS and ‘Best Picture’ today.

With the country’s revised Motion Picture Law lifting heavy restrictions on the consumption of foreign films from 1988 onwards, the 90s was marked by a new generation brought up on Hollywood imports. These were formative years for the key directors of the Hallyu wave – Bong Joon-ho included – but long before tantalisingly stylish films like Oldboy, Park Chan-wook was guilty of wearing his influences a little too clearly on his sleeve.

The Moon Is … The Sun’s Dream is a gangster melodrama that tries hard to pass as a moody film noir. All the key references points are in check: jazzy saxophone music; contemplative voice-over; photographers, gangsters and femme fatales. But despite a promising genre framing and a story about forbidden romance (and stolen gangland cash), the film trips over its own sentimentality. It doesn’t help that it looks like it was shot on the set of an American sitcom.

Park claims the film was made as a result of “blind ambition” in his twenties, but the movie’s commercial and critical failure almost convinced him to abandon filmmaking entirely. He’s even claimed that he’d like to burn every copy still out there – and has worked hard to keep it out of the public eye in recent years. But as a historical document, The Moon Is … The Sun’s Dream offers an illuminating starting point. It offers few hints of the emphatic style Park would cultivate in later years, and yet it does highlight a stubborn desire shared by many of his peers: to be better than Hollywood.

Judgement, 1999

In 1995, the collapse of the Sampoong Department Store in Seoul caused the deaths of 502 people – it was the deadliest structural disaster in history up until the September 11 attacks on New York. Attributed to criminal negligence on the part of the Sampoong corporation, who had removed vital support columns against the advice of the building’s contractors, the collapse resulted in a series of prison sentences, and huge payouts for the families of the victims.

But the compensation programme was flawed. Allegedly, some immoral members of society made falsified claims that they had lost loved ones in the incident in order to capitalise on the much-publicised payouts. This moral indecency serves as the backdrop to Park Chan-wook’s 1999 film Judgement, a 25-minute short about two different families claiming ownership of an anonymous body in a morgue.

Filmed in black-and-white, and interspersed with real documentary footage, this overlooked work feels like a contemporary take on the classic courtroom drama 12 Angry Men. And while evidently inspired by Hollywood, Park is, nonetheless, far more successful in crafting an engaging piece of work on this attempt. Innovative camerawork, complex shot framing and expressionistic use of colour establish a stylistic groundwork for much of the director’s later projects. Park’s winning streak started here.

Joint Security Area, 2000

While now somewhat overshadowed by the global successes of his later hits, Joint Security Area was the dramatic breakthrough that cemented Park as a leader within the emerging Hallyu film movement. Nominated for the Golden Bear at Berlin off the back of a box office record-breaking release in South Korea, JSA marked a significant cultural shift by becoming one of the first South Korean films to paint North Korean characters in a relatively positive light.

It follows a military investigation into a shooting that has left two North Korean border guards dead in the Demilitarised Zone. Such an event could spark full-blown war – but the deposition finds that at the heart of the incident was a doomed friendship between soldiers on both sides of the border. Featuring some sensational turns from superstars Song Kang-ho (Parasite) and Lee Byung-hyun (A Bittersweet Life), JSA offered a hopeful dream for a generation who sought an end to the years of friction between two sides of a once united country.

Released three months after a historic summit between Presidents from both sides of the border, JSA truly captured the public zeitgeist by offering a fresh, liberal attitude in time for a new millennium.

Never Ending Peace and Love (from If You Were Me), 2003

Park’s contribution to this 2003 anthology film, funded by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, tackled the theme of discrimination by focusing on the real-life tale of Chandra Kumari Gurung. The Nepalese migrant labourer was working in South Korea in 1993 when she was arrested for failing to pay for a bowl of ramen. Due to police negligence and professional misconduct, the woman – who spoke only Nepali, and wore ragged clothes – was institutionalised under the belief that she was mentally challenged.

In Park’s retelling of the events, the camera occupies Chandra’s point of view – forcing the viewer to identify with the maligned immigrant as she attempts to communicate with a series of oppressive figures; restaurant owners, police, and even doctors. At one point, when they begin to suspect she might be a foreigner rather than a “mental patient”, those in charge bring in a Pakistani interpreter to parlay. “Koreans think Pakistani and Nepali are the same,” the man explains, upon failing to establish a linguistic common ground. “We’re both a little black.”

The black and white film eventually bursts into vivid colour at the climax, as Chandra finally returns to Nepal. She had spent over six years incarcerated against her will, and the seriousness is not lost on Park.

Cut (from Three … Extremes), 2004

US production and distribution studio Lionsgate attempted to capitalise on a trend kick-started by Japanese horror movie Ring, in 2004, by funding an anthology of three shocking short films by directors from across East Asia. Joining Hong Kong’s Fruit Chan and Japan’s Takashi Miike in the director’s seat was Park Chan-wook, who would hit the big time that same year as Oldboy became a global phenomenon upon it’s screening at Cannes Film Festival.

Park’s contribution was a 40-minute staging titled Cut. Starring JSA's Lee Byung-hun, and largely-confined to a single set, it follows a wealthy film director who wakes up bound by a crazed fan, who has transformed his lavish home into an elaborate torture device. The filmmaker is given a choice: either kill an innocent child, or to let your wife suffer a slow death on the opposite side of the room, where she sits glued to a grand piano, held in place by a series of wires. The title bears a dual meaning: it refers to both the act of stopping the cameras from rolling during a film shoot, as well as the violent nature of the aggressor’s torture methods.

Released at the tail end of the “extreme” Asian cinema boom (effectively replaced by a more nuanced appreciation of South Korea’s Hallyu wave thereafter), this Saw-like slice of action evokes themes that would come to define Park’s career in later years: morality and class conflict. But it also shines a light on the now fully-formed style of South Korea’s then-leading filmmaker, with a rich set design, bold use of colour and experimental camerawork defining a production that is as elegant as it is scandalous.

Arrow Video just released Joint Security Area on Blu-ray in January to celebrate its 20th anniversary.