Adam Curtis’ new six-part marathon Can’t Get You Out Of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World opens in typically Curtis-ian style, with the 65-year-old softly spoken Brit announcing over footage of an eerily still, skyscraper-laden business district that “we are living through strange days”. His 2016 film Hypernormalization starts the same way, with the pronouncement that “we live in strange times”. There is perhaps a case to be made that life is inherently peculiar (I’m sure the Middle Ages was weird) but Curtis is right about our current predicament – society is breaking, people feel helpless, and despite the emotional and social closeness theoretically made possible by technology, there is an unshakeable aura of disconnect lingering like smoke on the walls. This uncertainty was certainly present pre-pandemic, long before times became unprecedented too.

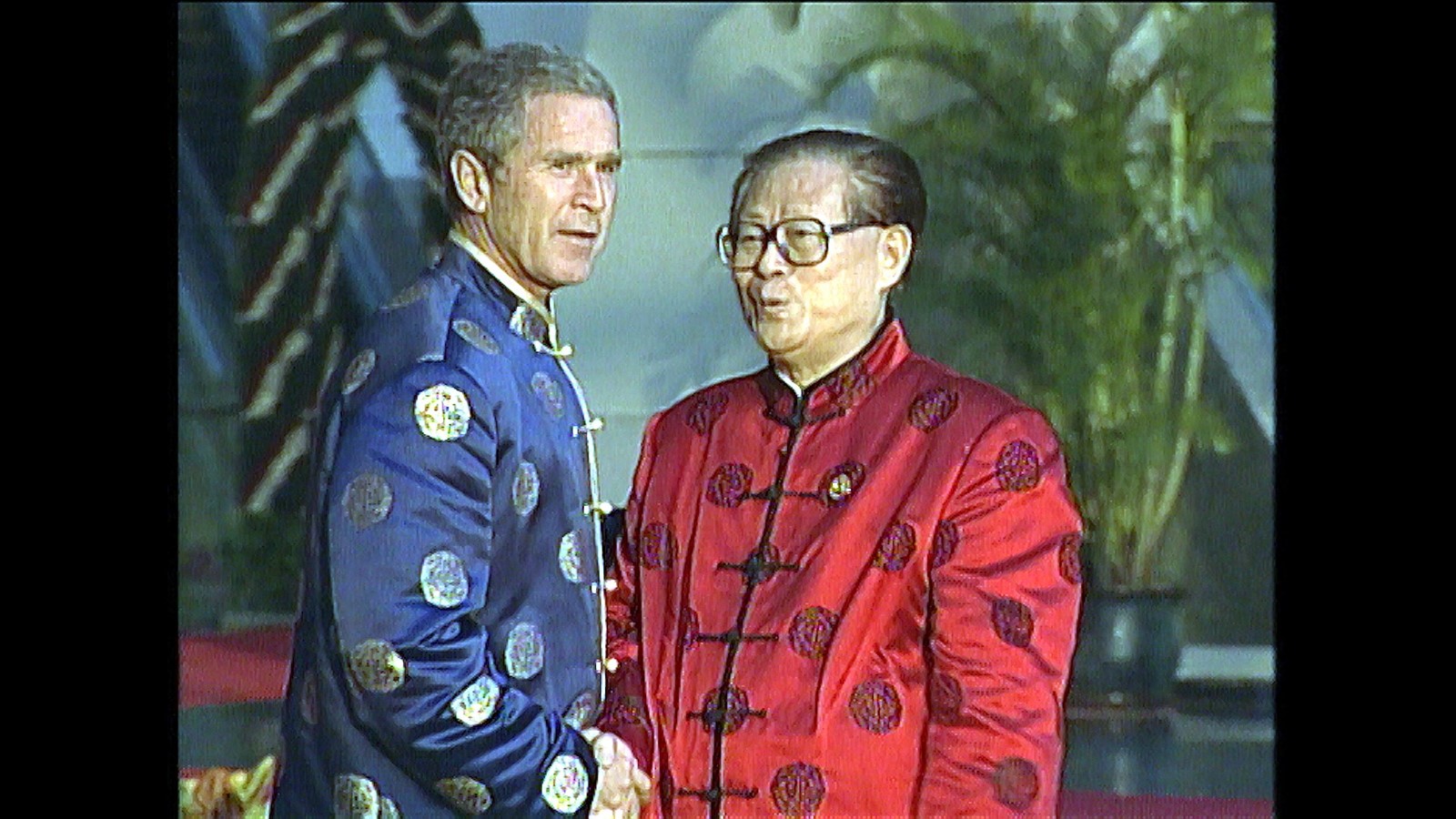

Can’t Get You Out Of My Head, launched on BBC iPlayer, is an enchanting exploration of how we got here, analysing our modern world through events of the past and the people that defined them, with a rotating cast appearing multiple times throughout the labyrinthine, eight-hour series. Jiang Qing, actress, wife of Chairman Mao, and communist revolutionary is a key component. Tupac Shakur and the Black Panthers feature, along with the Sackler family, who many believe to be solely responsible for America’s opioid crisis. Curtis joins the dots between these seemingly unrelated people to present a vision of now and the reasons for it, interrogating power structures, the rise of individualism, and the consequences of what he describes as how politicians gave up on having big ideas.

True to Curtis’ style, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head encourages the viewer to dream, drawing on his idiosyncratic style of stitched together archive footage soundtracked by post-punk, Aphex Twin, and hauntological synth experiments. “People don’t understand this about what I do,” he says. “I don’t look at what’s called the cut stories, I find them depressing and boring. I go for raw material, the unedited ‘rushes’. It’s camera people waiting for the reporter to turn up so they just film stuff. It’s really odd, it’s dreamy. I’ve actually got hundreds of thousands of hours of it, because I was collecting it. I have no idea what to do with it because it has no story to it, it’s halfway between raw experience and news items. It’s quite weird, it’s another kind of reality. That’s what I spend my time doing.”

I spoke to Curtis about his love for TikTok, conspiracy theory, and why he couldn’t have used Kylie as sound design in Can’t Get You Out Of My Head. “It’s one of the great pop songs of all time,” he says. “I can’t use it in the film, it wouldn’t be right. It would be too obvious.”

Thomas Gorton: Paranoia is a recurring theme throughout your films. How have you seen this grow over the past year?

Adam Curtis: Our society is rooted in the sense that when things are good, it’s great to be an individual and great to be able to go shopping and buy something that you can express yourself with. But when things go bad, it gets quite scary and lonely. And in that space, you start to invent all kinds of stories. This is what I’m trying to point out in these films, especially when those in charge of society no longer have a big story to tell you. Those who are close to or in power, they have no other vision than just keeping this stable. With the pandemic, paranoia has accelerated but I don’t think it just came from that. People were so shocked by Brexit and Trump, that they started imagining all kinds of dark theories about Vladimir Putin, rather than facing the reality of politics in power – which is that actually you’ve got a shitty society at the moment and you should do something about it, if you think you are radical. Everyone gets affected by it, even those who would never think of themselves as prey to paranoia.

“It’s in the interest of these companies to push things that just keep you online, anxious and angry” – Adam Curtis

TG: I think now we feel so far away from power that a sense of distrust has encouraged people to turn on each other, particularly online. How do you see a way out of that?

AC: You take back power and control of the internet, from the venture capital firms and large advertising firms who seized control of it. There are two ways of brutally running this world that have little to do with democracy. One is the Chinese model where you just don’t give a fuck about what people feel like inside. You observe their behaviour, give them treats to make them behave the way you want them to and if they don’t respond to the treats, you reprogram them like Uighurs in large camps. The opposite is to do what is emerging in the West, where you actually increase people’s emotions to keep them online more. I do think the thing that’s really fascinating about our time is the rise of higher aroused emotions created in viral internet factories. Anger, suspicion, distrust, outrage all keep you online longer, engaged. Therefore, it’s in the interest of these companies to push things that just keep you online, anxious and angry. That’s a decayed idea of what was a utopian idea of the internet. A lot of what you feel inside you doesn’t come from inside you, it comes from the society that’s around you.

TG: You’ve long been outspoken about the ills of social media, but you seem to know a lot about the mechanisms of it. Have you ever had a presence on social media?

AC: I have a Facebook account which I use for research. That’s all I do, I don’t post things on it. I tried Instagram for three and a half days and got so bored. The only thing I love is TikTok – I don’t do TikTok videos but I love TikTok. It has a scrappiness to it that I like. Instagram is a bunch of buttoned-up design Nazis as far as I can see, very uptight and very over-designed. What I also like about TikTok is I’ve discovered what’s called alt TikTok. There’s a really big discussion in politics done in really imaginative ways. I’ve made a TikTok but they won’t let me release it. It’s all about the CIA, China and an influencer I’ve made friends with who I think is incredible. I use her image at the end of the trailer I’ve just put out. She does that flash warning thing which is very big on TikTok at the moment. I’ll send you it and you can have a watch.

“I don’t want to be on social media because I don’t like being watched. In the age of individualism, one of the things that lurks in the back of people’s minds is the sense that they’re being watched” – Adam Curtis

TG: Thank you very much.

AC: I don’t want to be on social media because I don’t like being watched. In the age of individualism, one of the things that lurks in the back of people’s minds is the sense that they’re being watched. They’re very self-conscious and it is one of the things we haven’t really got to grips with. There’s a self-consciousness of our age. We always behave as though we are being watched, when we’re not. It’s just there and it’s a thing. It’s very inhibiting.

TG: Do you think there’s self-consciousness in art and culture at the moment?

AC: Yes and that’s led to a culture that’s constantly self-referential. I think there’s a thing that’s coming our way which is that actually culture may not be the radical thing we thought it was. One of the problems of our age is the whole idea that culture is the centre of everything and actually can be a radical force. It may be a very conservative force that constantly reinforces that self-consciousness that we’re talking about. Me being a sci-fi fan, where the new things are going to come from is something we don’t recognise yet. What I read at the moment is science fiction, Chinese sci-fi, African sci-fi. People like Octavia Butler, that’s the sort of thing I like. That sense that they’re trying to imagine something beyond the dimensions of the rigidity of now. I thought I May Destroy You was good. Every episode I had no idea where it was going and I loved that. I’d never seen anything like it. I liked that trilogy The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin.

At the moment though, I think a lot of culture is very self-conscious like the people. It constantly reinforces the world of its way. I blame people like Quentin Tarantino, and that early self-consciousness that came up in the 90s, post-acid house. There’s that moment from about 1992 through to 1996 when you started to get things that constantly referred to other things. Reality and the idea of changing reality began to disappear. To be honest, I’m part of the problem too because that’s pretty much when I started taking on bits of archive and slapping them together, in a knowing way.

“I thought I May Destroy You was good. Every episode I had no idea where it was going and I loved that. I’d never seen anything like it” – Adam Curtis

TG: Aphex Twin is all over the soundtrack in these films. Would you say he is an artist that imagines new worlds?

AC: What I think is brilliant about Aphex Twin is that he does two things. He combines in his lyrical work a wonderful expression of that yearning for something beyond. But then also expresses in other pieces the fractured and uneasy mood of the present moment. And to combine the two together is really what art should do I think. Showing you in a heightened way the mood of now – and the feeling of what might be beyond that. I think that that is also what SOPHIE did beautifully as well, jumping back and forth between the two without having to bother with the old idea of transitions. You see it in some modern films as well, the Safdie brothers for instance. Uncut Gems does that amazingly. And so does Michaela Coel. I find that really exciting.

TG: In Can’t Get You Out Of My Head you talk about how suburban Americans were easily hooked on Oxycontin in the 60s, because they were disenchanted, sold a vision of happiness that never arrived. What do you think we’re sold today?

AC: I think that’s a really interesting question. We are the drug. We are being used against ourselves. Those emotions have just been churned up in us and they have no meaning – we’ve become raw material for a new kind of industry. We’re the things being mined.

TG: The films talk about a flip in ideologies, and the idea that at some point people decided it was better to believe in nothing. It feels to me that actually people do have very strong ideologies now, people seem determined to believe in things that appear more patently untrue than ever before, like QAnon or The Illuminati. These are fringe ideas with relatively mainstream appeal. How did we get here?

AC: It’s partly the history I’m charting in the films. After the Second World War, people were absolutely horrified by what big ideas had led to; what Nazism, communism, fascism had led to. They led to horror. The alternative to that was individualism. It was rising up anyway, the idea that you don’t have big stories any longer, that they’re dangerous. People run away with themselves and turn hysterical, which leads you into that idea of being on your own. When it goes bad, all sorts of bad things crowd in and I do think that’s what I’m trying to get at in the final film. Everyone fell into strange, weird, dark stories built out of fragments that have no real logical meaning to them at all. It’s not just QAnon, it’s a belief that Vladimir Putin gave you Donald Trump. Everyone fell into a rabbit hole because there was no explanation given to them by the society of why strange things like Donald Trump or Brexit were happening. They just came out of the blue. Those in power have no explanation for it. So you have working class, middle class and upper class people who feel completely lost. They search for explanations and God bless the internet, it gives it to them.

Can’t Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World will premiere exclusively on BBC iPlayer on 11 February 2021.