The Forgotten Women author reflects on love, family and the nostalgic power of nature

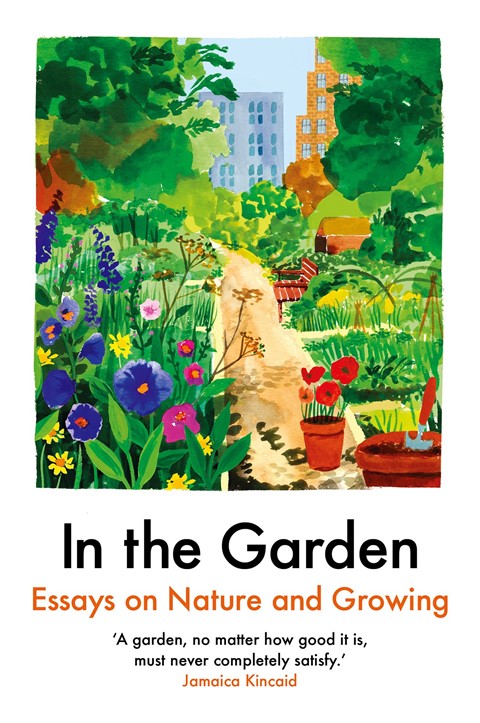

This excerpt is taken from the essay A Ghost Story published in the collection In the Garden: Essays on Nature and Growing – a new book that sees 14 contemporary writers explore what is most engaging and urgent about gardening today – published by Daunt Books.

According to my mother, if your plant needs flowering, you should steep banana peel in water over the course of a week and then dilute this liquid one part to five parts water, and then water your plants with the mixture. This always works for her orchids. If you have a barbecue, you should keep the charcoal ash and then mix it with soil around the base of your plants to fertilise them. And my mother’s motto for gardening?

What’s the worst that can happen? It’ll grow back.

I never cared about gardening until my mum’s almost-heart attack. I had pot plants, but they were meek, docile things; funky-shaped succulents and tiny cacti, plants that needed no love and thrived on neglect.

When I moved into a house in London with a garden, my mum was the one who came over on holiday and pruned it all back, revealing a small Japanese maple tree, rambling roses with teacup-sized yellow flowers and a malnourished olive tree.

The Japanese maple was her favourite – the Acer tree came to about her chest and had drooping, red leaves that looked like they were weeping rusty blood. She tended it religiously, clipping off the spindlier branches and packing it with fertiliser. Objects appeared in my garden – a toolbox, a bubblegum-pink gardening stool, a pop-up bin for foliage. Then birds: tiny wrens, sparrows, occasionally blue tits – and animals: squirrels, the neighbourhood ginger cat, purring on the top of our fence and begging us to let her in. Bags of compost were hauled into the garden – despite being in her sixties, my mother is still the strongest person I know – and once I came home to find my six-foot-high monstera plant repotted into something big enough for me to sit in, its roots gently exhaling after its release from the plastic enclosure I’d bought it in.

She took me to a garden centre – all this time I’d lived in London, and I didn’t even know where my nearest garden centre was – and we pushed an enormous trolley and stacked it with plants I didn’t know the names of. There was an entire courtyard dedicated to herbs, where the scent of apple mint and lavender perfumed the air. Sometimes we walked through the gentle mist from a garden centre employee hosing down the plants. The air smelled of loam and earth, that after-the-storm dampness that makes everything smell so fresh, like God had just turned you out of the Garden of Eden. It reminded me of Singapore, where the humidity builds in a sweaty, sour cloak and finally tears out of the sky to wash everything away, all rain-kissed and new.

Selfishly, I let her get on with my garden on her own. A nice holiday activity, I told myself. A retirement hobby for old people. Then she left for Singapore and her almost-heart attack followed, and so did I, flying back for her operation. When I returned to London, I found myself crying in front of that Japanese maple. I’d left it alone too long during my Christmas in Singapore and that night in the hospital; hadn’t given it the right amount of water, or coddled it with fertiliser, or simply hadn’t talked to it enough, in that low tender voice my mum always used with plants, half talking to herself and half talking to whatever was in her gloved hands, so raw and green. Either way, it was dying. Its leaves were almost burnt away to a pale crisp, drooping in an unnatural way. Half the branches were bare.

Obviously, I knew exactly what was happening here – after all, I’d had therapy; even if I was in an ‘unhealthy’ psychiatric arrangement, I could tell I was projecting.

A mother isn’t a tree, and a tree isn’t a mother. It wasn’t even the right colour or shape to be my mother, who was sturdy and brown in a way that an Acer isn’t. But the brain works in clichés – you can try to fight it, but no matter how much European cinema you watch, it’ll always be the Hollywood rom-com that makes you cry.

In the Garden: Essays on Nature and Growing, published by Daunt Books, is out now.