There’s more to Jack Guinness that meets the eye. And what meets the eye is a male model, who is as recognisable from his work for brands like Dolce & Gabbana and Dunhill as he is from the diary pages of newspapers and magazines, where he would – in normal, pre-Covid times – be pictured at the most fabulous parties, in the most fabulous clothes. For all intents and purposes, he appears like a man who has breezed through life without a care in the world. But that’s only part of the story. What you don’t see is the journey that Guinness has been on and the fact that there were times that he didn’t think he’d make it.

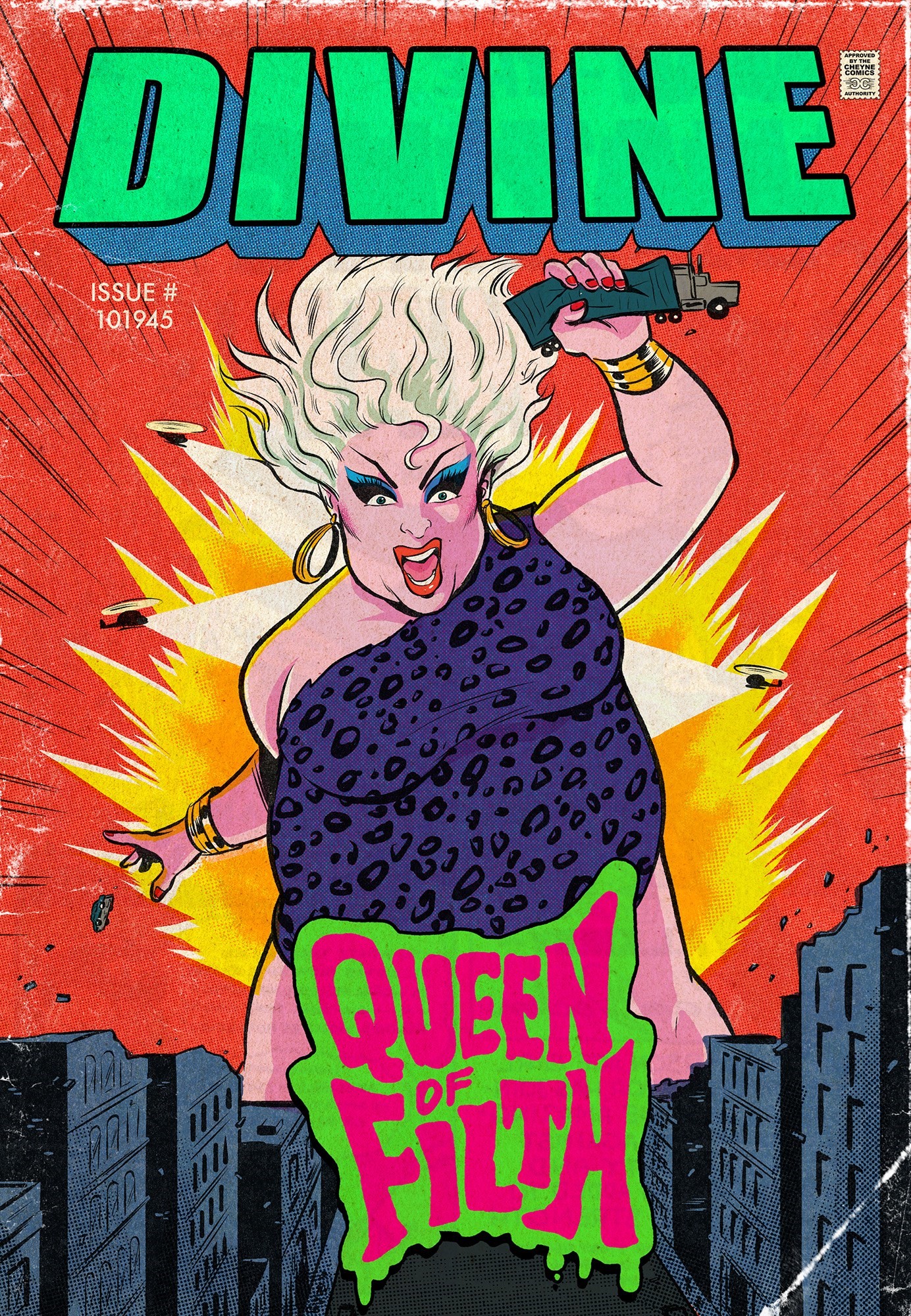

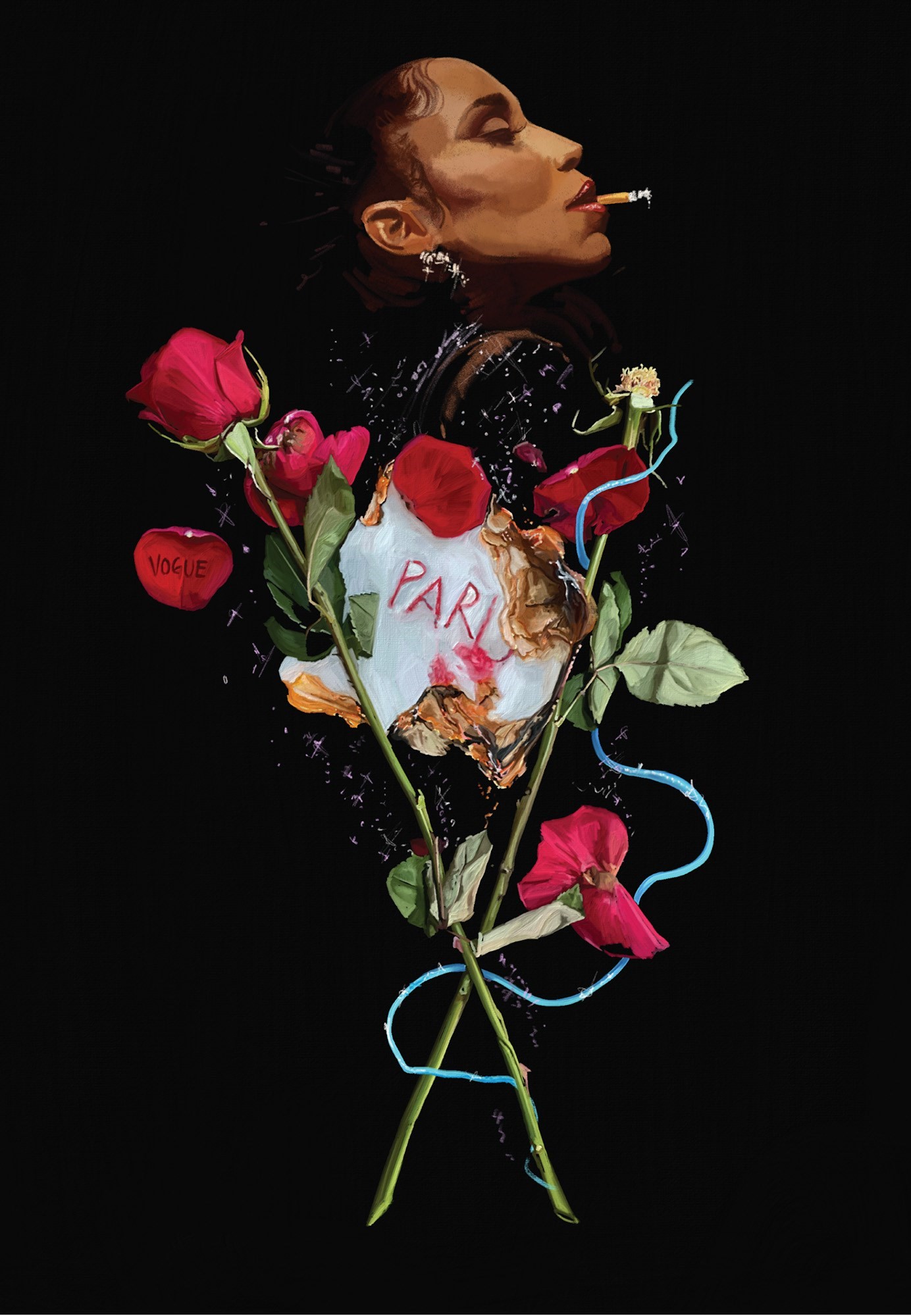

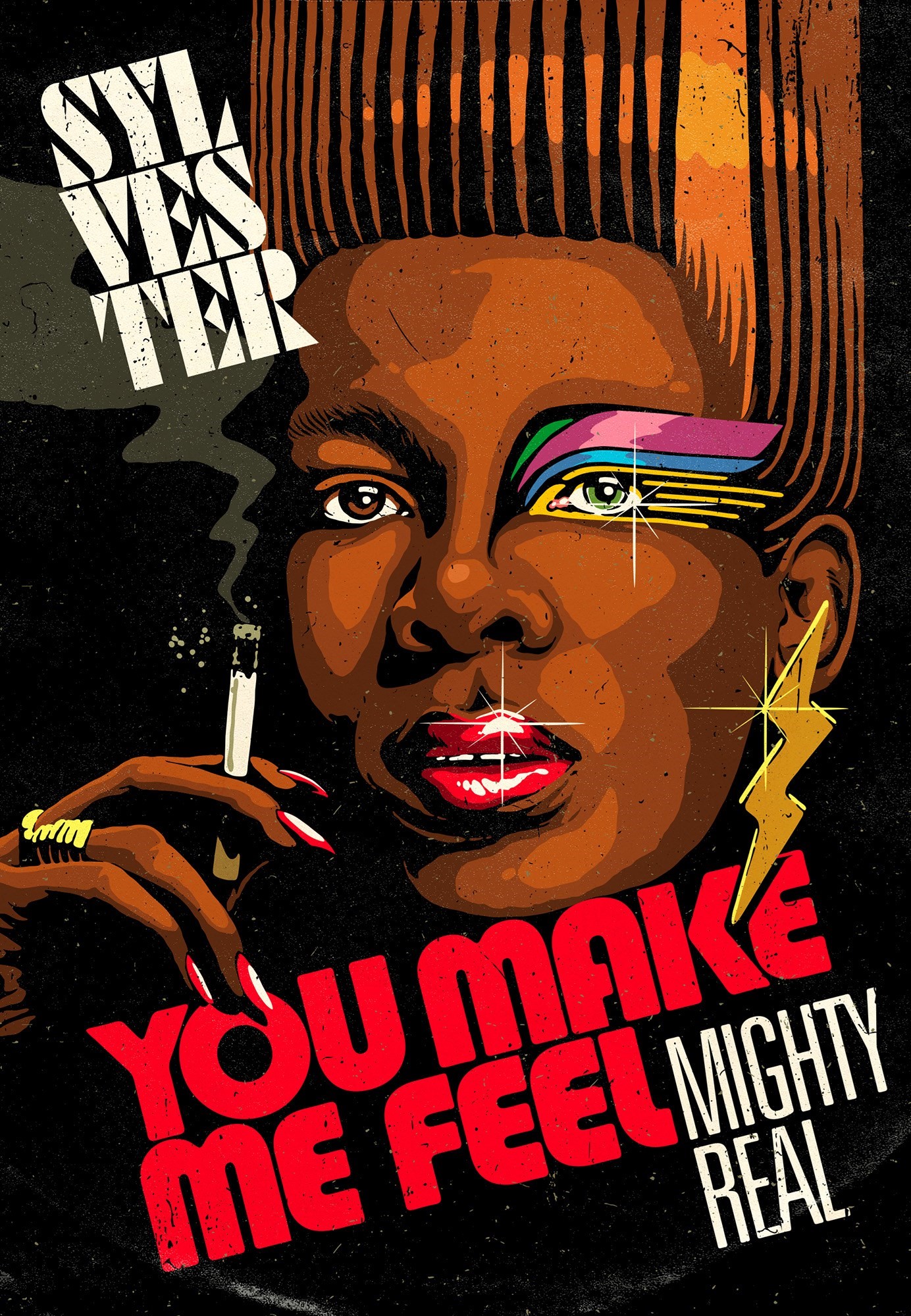

Born in London, Guinness was raised in a Christian family, the son of a vicar. The realisation that he was gay was, needless to say, less than convenient and his journey to self-acceptance – and perhaps most importantly, self-actualisation – has been fraught and often lonely. That’s what prompted him to launch The Queer Bible in 2017 – the guide to LGBTQ+ history and culture that he never had, where people write about their queer heroes. Fast-forward a couple of years and The Queer Bible is being released as a book, featuring essays by the likes of Elton John, Munroe Bergdorf, Paris Lees and Rainbow Milk author Paul Mendez – whose love letter to James Baldwin is excerpted on AnOthermag.com, alongside this interview.

Speaking the week before the book launch, Guinness admits that this project came at an opportune time – in the midst of lockdown – and that it was fundamental to maintaining his sanity over the past 12 months. “It saved my life,” he says, with only a hint of hyperbole. “My whole career has been about myself. But my book took me out of myself. And that was a really humbling but also mentally positive experience to go do. This is not about me, it’s about elevating other people’s narratives and stories.”

Guinness hopes that the book gives young LGBTQ+ people the roadmap that would have made life so much easier for him, as well as the knowledge that they are standing on the shoulders of giants and that they are not walking alone. Here, he opens up about the story behind The Queer Bible, and how he learned to exist in a grey, gay space in what can be a very black and white world.

Ted Stansfield: I want to rewind a bit. The Queer Bible was a website first. What’s the story behind that?

Jack Guinness: I had the idea for it about three or four years ago, when there wasn’t that much queer publishing going on. There was a lot of gay publishing going on, a lot of guys in speedos, but nothing that was speaking to a diverse, complex, politically aware, culturally cool group of people. I wanted a space where I could go and learn about LGBTQ+ history and so, I decided to make it myself, which was a mad thing to do because I was just going to parties and being a model.

I founded The Queer Bible and one of the first articles we published was by David Croland, Robert Mapplethorpe’s ex-boyfriend. He wrote about going to meet Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith at the Chelsea Hotel and stealing him off her. So you have this dual narrative: someone contemporary, who is alive now, and a story that pulls you into another time. I think there’s something powerful about this; about realising that queer lives mirror each other through time.

When I was realised I was gay, I felt instantly cut off from everyone around me – from my family, who were religious, from my friends … I felt really alone. That led me to have a lot of amazing experiences – I grew up in Zone 1 and could walk to Soho from my house, so I was going clubbing at 14, 15, and I had loads of great times. But I was also exposed to lots of predatory, horrible people and ended up in experiences I was a bit too young for. I think if I connected up to my queer history and my queer culture, or if it had been easier to do that, I would have saved a lot of time and heartache and [avoided] a lot of damaging behaviour that led to a lot of shame and pain in my life. So I really am quite evangelical about the power of connecting up to your history.

“I really am quite evangelical about the power of connecting up to your history” – Jack Guinness

TS: Pun intended?

JG: Absolutely, pun intended. I feel really positive about that. There’s so much information out there online, it’s overwhelming, so I kind of see my role as a curator, if that doesn’t sound too pretentious; of saying to kids, “these are interesting people.” What really works [about the book] is I didn’t tell people who to write about. That’s really important to me. It isn’t my book in a weird way, it’s my contributors’ book. I said to them, “who do you care about?” and there’s some really weird answers like Mae Martin, the comedian, picked Tim Curry from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. And then there’s Munroe Bergdorf who writes about Paris Is Burning and it’s just the most mind-blowing magic – and I mean that literally, it’s a magic essay, there’s power in her words. At the end she gets you to say the names of the children of the different houses from the Paris Is Burning ball scene and it’s like an incantation. It’s very moving and powerful.

It’s a learning experience for me and I come to the book as a student. I want to learn from other people and to share the knowledge that I’ve got, pass it on to the next generation, like an old queer drag mother.

TS: From the legendary house of Guinness.

JG: Fucking hell that’s probably trademarked, I’d get sued for that.

TS: I’m interested in the name and the use of “Bible” – I come from a religious background, and it’s quite contentious … ?

JG: I talked to my therapist a lot about it. I had the website ready to go for eight months and I didn’t release it because I was so scared of upsetting my family. But the idea of the name … there is something in it that is a bit ‘screw you’ to organised religion. There is something about co-opting the word and about the fact that, for so long, LGBTQ+ people have been oppressed and excluded by religion. It was like “let’s have our own holy text, let’s have our own sacred history, that’s ours.”

Paul Mendez, who wrote Rainbow Milk, writes a beautiful essay on James Baldwin, which is one of my favourite essays in the book. He comes from a religious background, and his work gets me thinking a lot about my own family and about how, in cancel culture, it’s really easy to say “no, I’m not gonna listen to your point of view, I want to get rid of you.” But you can’t do that if it’s your mum and dad. You have to find a way through. The Queer Bible is about trying to bring those two worlds together in a way that works for me.

Ruth Hunt, the ex head of Stonewall, did a book called Queer Prophets where she got people that have either come from religious backgrounds, or have a religion or spirituality, [to write about their personal journey with religion]. I wrote a lot about mine, and how damaging I’ve found trying to amalgamate faith and sexuality; how difficult that has been for my own identity, how traumatising that has been. For me the concept of greyness has been very helpful. Everyone wants things to be black and white: we want goodies, we want baddies, we want things to slot into these easy frameworks because it helps us. But we’re so much more complex than that. And to me the concept of greyness – of allowing this muddiness, this murkiness, this mix in myself and in others – is really freeing because it allows you to forgive and come from a place of love, without sounding too much like a shit Oprah Winfrey. This has taken years of therapy to get to …

“From the outside I have a huge amount of privilege ... People don’t see the family stuff, the huge pain and trauma it took to be who I am” – Jack Guinness

TS: Yeah, it’s tricky to cancel people if you’re related to them. You have to do the work, and be like ‘let’s talk about this, let’s wrestle with it,’ and come to some sort of resolution. I know some gay people who never even had to come out, who have never met any resistance. Whereas for others, it’s come at a real cost. It’s been a battle. There have been casualties. And they’re left with scars. Some people just bounced out the womb …

JG: Yeah! And that’s beautiful and I’m really happy for them, but I’m jealous too – it’s a privilege. From the outside I have a huge amount of privilege – I’m a white cis man who has been able to control his queerness so that I can work in quite heteronormative spaces, like male modelling. I’ve butched it up (which has been to my psychological detriment) and played it straight on certain jobs for money, which does make me feel a bit sick. I don’t do that anymore but that was my survival. People don’t see the family stuff, the huge pain and trauma it took to be who I am. And that’s something that I kind of carry around with me privately, a lot, that I nearly didn’t make it, like I nearly wasn’t here today. Yes I’m here now in a fabulous outfit, but it was hard! [Laughs.].

TS: I guess it shows the limitations of identity politics in a way – you’re a privileged cis white man, but you’ve also struggled. There’s stuff people don’t see.

JG: Yeah, I was talking to Paris Lees about this. I was talking to her about her book, and she was like, “I don’t know what it is in me that needs this to be public. I’m literally going through the most private, traumatic moments of my life and there is something in me that wants it heard.” I get that. You want people to know what you’ve gone through to get where you are, and I don’t know if that’s unhealthy or healthy – I don’t really judge it – but I have that in me. After this project, there are certain areas I want to speak about more, like religion, sexuality and gender, if I’m brave enough. I think it would be really healing, not just for the queer community, but for religious people as well because I grew up religious and I know where they’re coming from. I feel a weird responsibility to speak into that world, and it terrifies me, but I think that’s what I’m called to do, to use a religious phrase. Oh god, I’ve got a messiah complex.

TS: Or you’re a queer missionary.

JG: I’m a queer missionary. All my ancestors are missionaries, going back generations. So my dad is a vicar and growing up as the son of a vicar, it’s really weird, the pressure you feel to be the good kid. People were watching you to slip up. I very much had that thing of like you were either an angel or you were the devil. So when I went off to the queer world, I was like “right, well, I’m evil now.” But there’s a middle way, you don’t have to be completely self-destructive. It’s about that grey space.

TS: The Christian language we grew up around, it’s very “light versus darkness, good versus evil.”

JG: It’s very binary. The essays in the book really challenge that binary and are about sitting in that ambiguous space of identity of sexuality and gender, and to me that’s a really scary space, because it feels like I’m not on firm ground – you know if everything’s in nice, neat boxes, I can handle that. But I think a real sign of maturity is to sit in that mystery and be OK with it.

“When I came out to my parents, I prayed (I’m not sure who to) for the words to say it in a way that they could understand and the phrase, ‘I want to stand in truth with you’ came into my head” – Jack Guinness

TS: To exist in the mystery, that’s how I’ve come to articulate it.

JG: That sounds like a really shit band name, I love it. Shall we start a band? There’s a lot of money in that, the pink pound and the Christian pound.

TS: A winning formula. The world is too complex [for categories], which is actually kind of beautiful.

JG: But this is my point. It is more beautiful, if you’re brave enough to face it. When I came out to my parents, I prayed (I’m not sure who to) for the words to say it in a way that they could understand and the phrase, ‘I want to stand in truth with you’ came into my head. Which is the most un-me phrase. And I said that to them. That’s the one thing I can be sure of when we’re talking about the binary: that the truth is good. It can be painful, it can be messy, it can be scary to look at, but it’s good. I think that’s what my journey is and I think that’s the journey for a lot of the contributors, we’re all trying to get to a point of our personal truth – who we are, where we come from and that process of becoming (again to sound like Oprah, but it’s a really important one).

I’m definitely happier now – coming from a religious family, releasing a book called Queer Bible, these all quite scary things; things that little, positive Jack would have been terrified of; things I would have thought would have killed me. But I’m here and am genuinely the happiest I’ve ever been in my life. And I want to share that with young people – it’s a cliche and I hate the phrase, but it really does get better.

Pre-order a copy of The Queer Bible here.