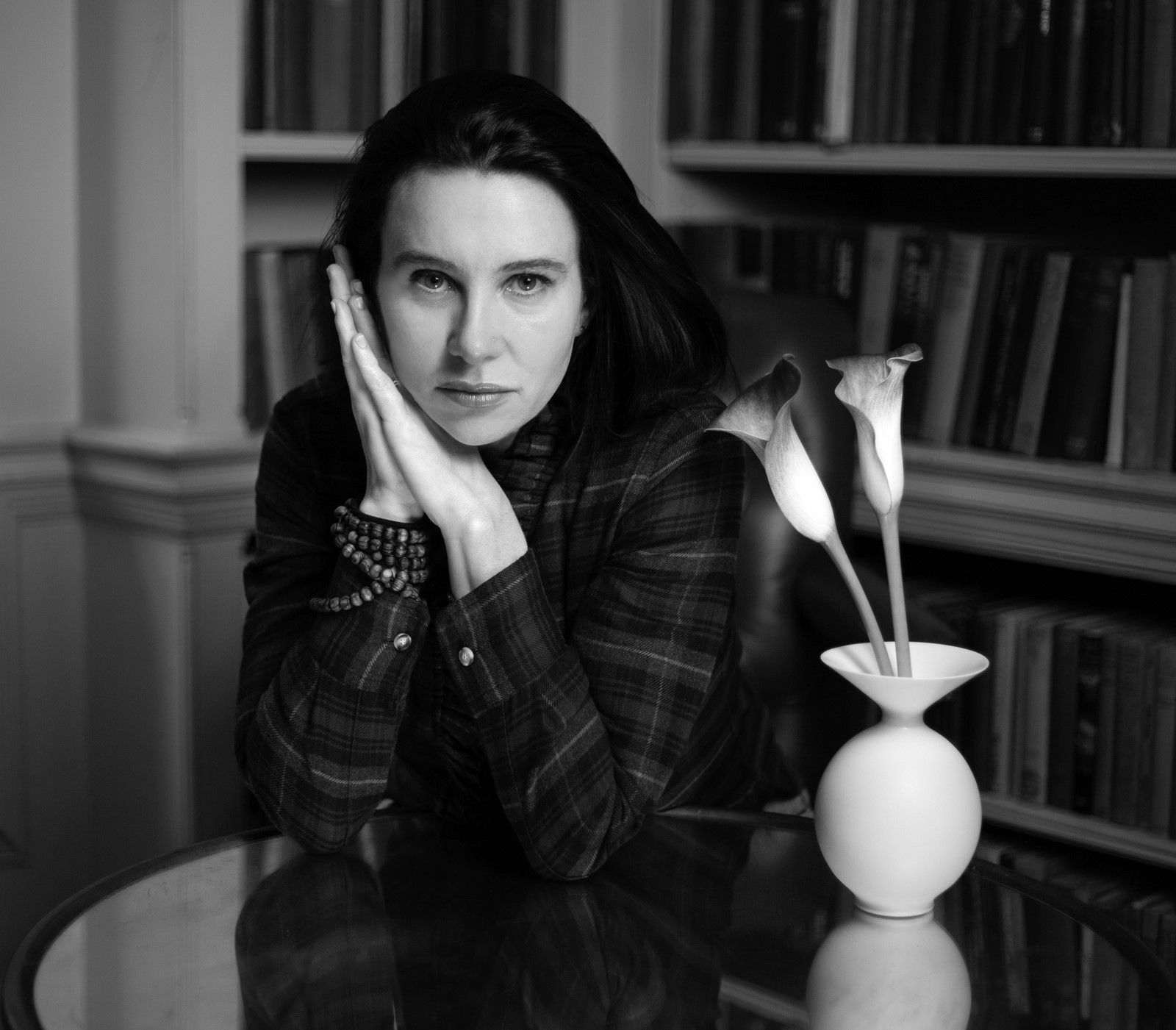

Lisa Taddeo is angry. A few days ago, she opened her front door and unleashed a single, blood-curdling scream into the wind. The howl was directed at a group of internet technicians who had been ignoring her repeated, polite pleas not to touch her phone line. They blanked her, and in the middle of a frantically busy work week, cut off her internet connection. The scream was for them, but also for every man who has dismissed her over the last few months (there have apparently been many). “I wanted everybody out there to know that I was fucking pissed, so I literally just opened the door, screamed, and closed it,” she recalls. “My husband was like, why did you have to do that? Now everyone’s scared of you.”

I am talking to Taddeo over Zoom from her home in rural Connecticut. There are some signs of residual stress – her cropped hair is tousled, her voice is tired and husky – but otherwise she is in good spirits. After all, despite the rage-fuelled screams, there is plenty for the author to look forward to: her bestselling 2019 non-fiction book, Three Women, is currently being turned into a television show (they are casting actors now), and Taddeo is taking on the role of screenwriter and executive producer. As well as working on two other books, she is also about to release her first-ever fiction novel: the hotly anticipated thriller Animal. “It’s been a lot,” Taddeo says, when asked how she’s coping. “Every moment is like, a moment.”

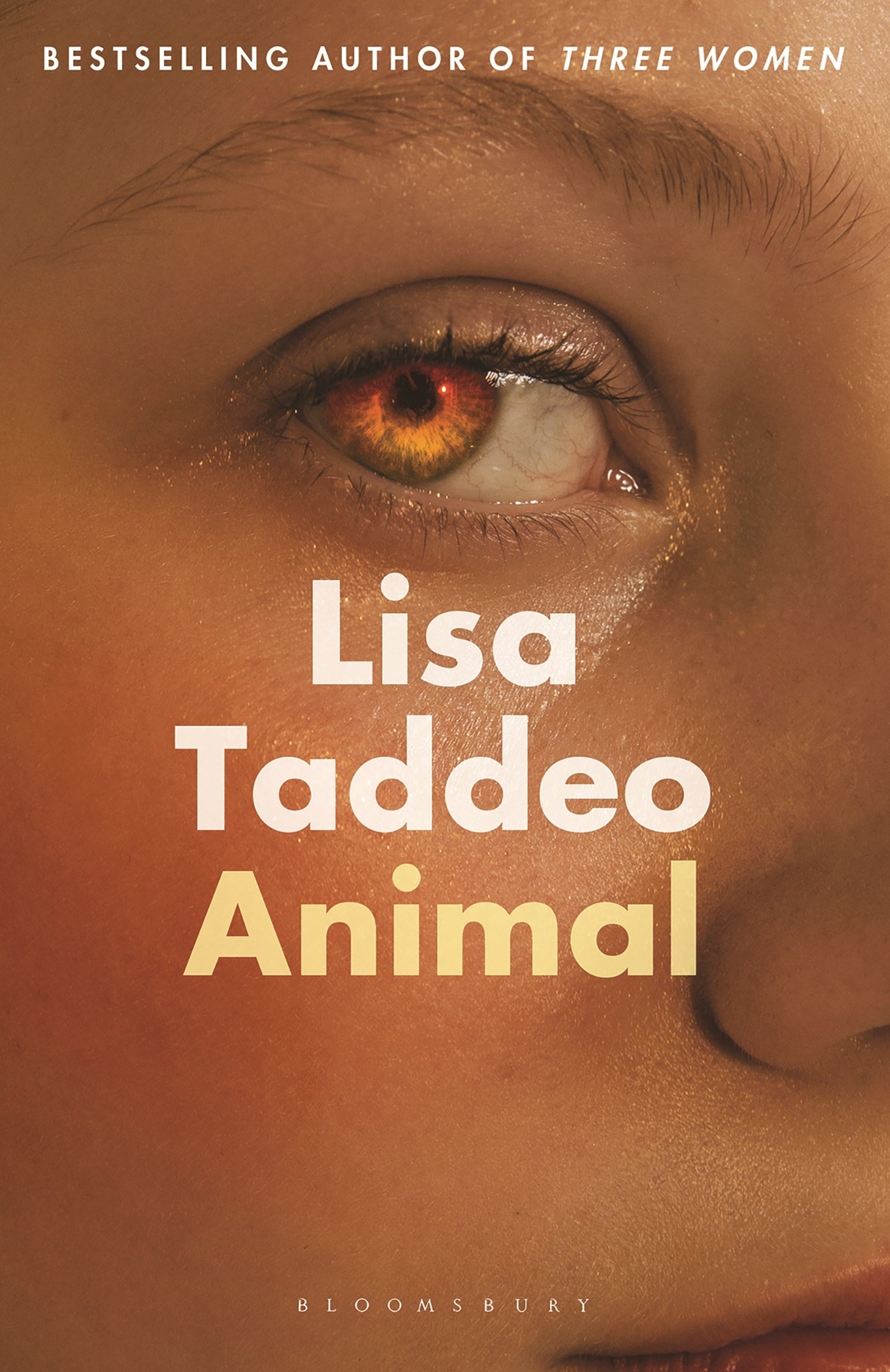

It is hard to talk about Animal without giving too much of the plot away, but fans of Three Women may be surprised. While the latter was a study of feminine desire, her new novel ventures into much murkier depths of the psyche, with equally emotive results. Told from the perspective of charismatic anti-heroine Joan, Animal is an unflinching exploration of grief, repressed rage, and the slippery, metamorphic nature of trauma. Here, Taddeo tells us more about the issues that inspired it.

Dominique Sisley: Three Women was a colossal success. Most of the women I know loved it passionately, but a lot of others rejected it or got quite angry about it. Why do you think it was so polarising?

Lisa Taddeo: My goal with it was to get an interior of women’s minds. I wanted to show how we love. We’re not all the same in who and what we love, but in wanting to be seen and loved for who we are, we are so very similar. It was really important to me for the reading experience to be an immersive one and to try to show empathy, wherever possible, so that people can see themselves in the women.

I didn’t think it was going to inspire strong reactions, but I think that it sometimes felt a little too close to home. Some people don’t like to look in a mirror, or they’re not ready to. I’m not saying that to be like, “oh well you didn’t like the book because you weren’t ready to look at yourself” – I don't mean that. But with the character Lina, [a housewife who has an obsessive affair with an apparently indifferent man], I noticed certain people were calling her pathetic. Often, that was because they had experienced the same things that Lina had, and didn’t like to be reminded of it. They didn’t want to see that obsession in themselves. When you’re put off by something, I think it’s easy to try to distance yourself from it.

DS: Your new book, Animal, shifts the focus from feminine desire to rage. Why did you want to write about that emotion? Is it something that you’ve seen or experienced a lot in your life?

LT: It is as much a story about rage as it is a story about grief. I’ve had a lot of grief and seen a lot of grief. And I think that when I’ve seen people get really angry or upset, I’ve understood it implicitly because of my own experiences. I think grief is one of the biggest sources of rage. Like, why did I have to suffer this? Why did this person, who was a bright shining star, have to leave? Why not that person over there who is a disgusting monster? It’s that kind of feeling. And women are not really able to get upset or angry without getting called crazy or bitchy or annoying – I mean there are just so many words we have for women who are angry. Crazy bitch. That is what we have. But when men are angry, it’s this almost beautiful thing, you know? It’s noble.

“With women, there’s the big Madonna-whore construct. It’s like, do you want to be a good girl or do you want to be a bad girl? But I think that we live variously as one or the other throughout our lives” – Lisa Taddeo

DS: The main character, Joan, could be called all of those names. At times she’s angry, insecure, unkind, twisted and bitter. She’s also promiscuous, and frequently the “other woman” in her relationships. There’s never any judgement, though.

LT: With women, there’s the big Madonna-whore construct. It’s like, do you want to be a good girl or do you want to be a bad girl? But I think that we live variously as one or the other throughout our lives. But there’s no “other man” in the same way as there is the “other woman.” Men are often forgiven for their transgressions, as though if they don’t have this extramarital liaison they might shrivel up and die. But for women, she is committing a crime against femininity. I’m not saying being the other woman or the other man is OK and morally fine, but I do think it was important to me to see it as not being a gendered thing.

DS: Why are we so afraid, culturally, of that “dark” femininity? What do you think it stems from?

LT: There’s this desire to keep things as they are. It’s the same with race, too. There’s this desire to keep things the way they have always been, to keep things comfortable. It’s like, the other day someone was complaining to me about how we can’t say terms like “master bedroom” or “spirit animal” anymore. And it’s like, well, what are you losing? What’s so threatening to you about not being able to say these words anymore? You’re gonna find other words, that’s the beauty of language. And I think with gender, men – and even many women – are holding onto this construct they’ve become comfortable with. We’ve been living with it every day, it’s just what we know. People get really scared of change.

DS: Animal is dark. There’s betrayal, rape, murder, trauma, perverted sexual fantasies. What draws you to those depths?

LT: It wasn’t really planned. For me, a lot of stuff happened in my earlier life that foretold the way that I would live in the future. I’m interested in [these dark] stories because that’s the background of my own life, they’re what I feel closer to. I very much wish that my life were closer to a summer beach read, but it’s not. And so many of the people that I find compelling are people who have been to the depths and then come back to tell their story. I think that there’s just this sort of gothic darkness that is part and parcel of a lot of people’s lives. I don’t think it’s out of the ordinary; I just think a lot of those people aren’t telling those stories. They bury them.

“I am interested in [these dark] stories because that's the background of my own life ... I very much wish that my life were closer to a summer beach read, but it’s not” – Lisa Taddeo

DS: On the other side of that, there does seem to be a lot of people who don’t live those lives, or experience any kind of darkness at all.

LT: Yeah. It’s funny, as I get older, I find myself losing touch a lot with those friends of mine who don’t understand what I’ve been through and what other people have been through. I find myself gravitating more towards people who have been through a lot, or sort of courted darkness. It’s not even a matter of finding those people more interesting – I think it’s just a matter of finding a community of people that make you feel seen. And so for me, Animal is a book for those people: it’s a book for the people who have lived the same types of lives, and it’s also a book, hopefully, for people who haven’t, so that they may see what it’s like.

DS: Can you tell me a bit about those experiences? I know you’ve suffered a lot of grief.

LT: I was incredibly close to my parents, we had a very nuclear family, and my father died in a car accident when I was 23. And then my mom was sick with cancer a couple of years after that, and then my aunt and uncle, who we had lived with our whole lives, and then my dog and all of my grandparents. I lost them all in the space of six years. It was a lot. So I think that’s one of the things that put Animal into a certain darker zone, because I wanted people to understand that [this grief is] even worse than you can imagine. I wanted people to really understand.

DS: Do you feel optimistic for the future? Is there hope for women like Joan?

LT: I do, you know. I do. It’s hard because life is so cyclical and we go two steps forward and then two steps back. I think what is important is doing as much as we can in our own lives, and changing the script as much as possible. If you’re the parent of sons, educate them. We’re having a lot of conversations right now that are really, really great, and I hope that we keep having them. I think there’s hope for Joan, and I think there’s hope for all of us.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity

Animal by Lisa Taddeo is published on June 24 through Bloomsbury.