The author discusses her debut novel, Nightbitch – a surreal, beastly and searingly honest depiction of new motherhood

In the opening chapter of Rachel Yoder’s debut novel, Nightbitch, the unnamed protagonist is asked how she’s enjoying her life as a new mother. We witness her frenzied internal thought process as she debates her response. Her brain whirs through a series of desperate emotions: she is angry all the time; she is bingeing on fig rolls at midnight to “stop herself from crying”; she is afraid that she will never be “smart or happy or thin” again; her brain “no longer functions as it did before the baby” and she is “really dumb now”. She is also worried that she might be turning into a dog.

Nightbitch is a surreal and beastly book. The protagonist is a woman who has left behind a career as an artist for a new life in suburbia, where she is now a full-time mother to her sweet (but annoying) toddler. As she adapts, she notices strange changes start to occur in her body: her teeth grow sharper, a tail-esque bump appears on her back, and thick hairs begin sprouting in unusual places. She is also overcome by sudden, violent compulsions – to snarl at strangers, to gorge, even to kill. “I noticed that, in all the reviews, the word most used to describe the book was ‘weird’,” says the author. “I guess I can go with that.”

Yoder is speaking to me from New York, in the middle of a busy publicity tour, though she is normally based in Iowa City. Nightbitch is partly based on her own emotional experience of motherhood; on the isolation, hopelessness and rage she felt in the first few months of her son’s life. Although she is something of a literary expert – she has two masters degrees in creative writing, and has worked as an agent, festival programmer and editor – Nightbitch is her debut novel. We caught up with her to find out more about the experiences that inspired it.

Dominique Sisley: When did you realise that this story, this experience of motherhood, was going to be your first novel?

Rachel Yoder: After I had my son I stopped writing for two years. It’s not even that I didn’t want to write, it was that there was nothing I had to write. All of a sudden, I just had nothing to say; there was nothing to put on the page. So I found those two years at home – after I quit my job and became estranged from my creative self – to be incredibly challenging and incredibly lonely and isolating. But after those two years, something happened. It was right after Trump was elected, which sent me over the edge. It was a horrible time to be a woman and a mother in America, under a Trump presidency. I needed something to be playful and fun for me to get back into writing, but then it was also a vehicle for this, like, intense expression of anger and frustration. And I just ran with that – I sat down and realised I had so much to say, and I let myself rant in a way that I had never really let myself do in my writing. That voice had a lot to say, so I just followed it.

DS: I feel like there is not a lot that is communicated about motherhood – a lot of women seem to go into it fairly blind, especially if they’ve not seen close friends and family go through it beforehand. Did you feel shocked by how much it changed your life?

RY: I had watched my best friend have three kids, so I saw her as this [ideal] vision of motherhood: she was a very happy mother, and wanted to be at home with her kids. But the logistics of my life were very different. I didn't have a community; there were no friends or moms or family nearby. I didn’t think it would be a problem, but the isolation was really surprising to me, how hard it was to connect with other women. And then there’s also all this stuff that happens to your body. I knew about some of it from having a friend who had gone through it but, like, I didn’t know my hair would fall out. I didn’t know my feet would get bigger. I didn’t know that my periods would get weird when they came back. There’s this whole mysterious world of knowledge that just isn’t talked about and I don’t know why. I think it’s because we’re supposed to think that motherhood is sweet, nice, fun and easy, and that you’re just gonna have a great time with your kid. But it's not. It’s feral and dirty and intense. Or at least that was my experience of it.

DS: The Momfluencer Complex, and social media, doesn’t seem to help with that. There seem to be all these novel new ways to make mothers feel bad about themselves.

RY: Yeah. Not only are you supposed to be a mom, and do that perfectly, you’re also supposed to look good and be able to package it and put it out there for public consumption. Which is baffling, and feels very dishonest.

“Motherhood is an inherently creative act: you’ve made this beautiful thing and you want to devote your life to it ... But then, where are you in that equation at the end?” – Rachel Yoder

DS: In Nightbitch, you confront the more complex feelings about motherhood, including all the boredom, rage, resentment and regret that can come with it. Why do you think it still feels taboo to talk about this side of it?

RY: I think it’s becoming less taboo. Something both me and my husband really had to deal with after the birth of our child is that your life cannot function as it used to. It doesn’t operate in the same way, and all of your priorities are rearranged. Even my ambition got rearranged. I was working, but I was thinking that I would rather be home with my kid. I never thought I would have that urge, and I was sort of feeling betrayed by that. I was feeling betrayed by this profound biological change – this deep, visceral physical desire to hold your child and be with your child – playing against all this ambition I thought I had, all these career goals. I felt betrayed by biology. But it was just so undeniable, I couldn’t turn away from it. And that’s something I think I’m playing with in the book; this idea that our body has these new desires. What happens if we start to listen and embrace them?

DS: Are you comfortable with that biology now?

RY: Absolutely. I take a lot of like joy in it, it brings a lot of fulfilment to my life. Perhaps one of the lessons of Nightbitch is that, despite all of the beautiful biological mandates of your body, you still must attend to your dreams. You still must attend to the part of you that makes you you, whether that’s making art, or long-distance running, or whatever it is. For me, parenthood was this negotiation of giving part of myself away, while at the same time holding fast to the piece that I most needed, which was my creativity and my writing.

DS: Do you think that a lot of people – particularly mothers – end up losing themselves completely?

RY: Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s the struggle, not losing yourself. Because there is something very alluring about just giving yourself over to fully over to these beautiful things you’ve made – I mean, you kind of want to. It’s an inherently creative act: you’ve made this beautiful thing and you want to devote your life to it. And you do in many ways. But then, where are you in that equation at the end? I don’t know if dads do it better or if they have a similar struggle. I’d be interested to read that book, or to have that conversation.

“I think women are just desperate to be seen. They’re desperate to connect with other women. They’re desperate to be in community with each other”

DS: The protagonist of Nightbitch starts to turn into a dog. What does the dog – that wildness – represent to you?

RY: I think the wildness of Nightbitch is, in a sense, her wisdom. It’s the energy that can no longer be contained or looked away from and is trying to wake her up. The animal is this primal, fundamental wisdom that I think she’s lost touch with. I think that’s what Nightbitch is dealing with; all the messages [the protagonist] got from watching her parents’ marriage, and the legacy that we inherit as mothers of what’s good and what’s right and how a mom should be. In this book, I’m asking why. Why does a mom have to be that way? Why can’t a mom be crazy and play like a dog with her kid? Why do we just have this sanitised, singular image of motherhood? I was trying to explore if there was another way to be.

DS: How have you felt about the response to the book so far? Are you nervous about how it will be received?

RY: It’s really startling and overwhelming. I think women are just desperate to be seen. They’re desperate to connect with other women. They’re desperate to be in community with each other. And I think especially after the pandemic that’s really been clarified for a lot of people, just how much we are pack animals and we need each other to survive. We need each other to raise our young, and I didn’t realise how many women felt so isolated in motherhood. I think that’s a real crisis, and I hope that we’ll start talking about that: how we can how we can come closer together, and also how we can use this anger and frustration to activate ourselves toward changing things.

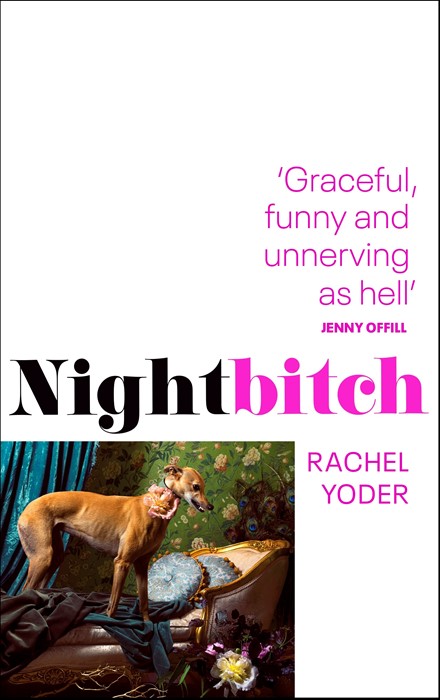

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder is published by Vintage Books.