As several Category III highlights are reissued, James Balmont takes a look at Hong Kong’s exploitation boom of the 90s

There’s nothing quite like the allure of controversy. And with Prano Bailey-Bond transporting audiences back to the height of Thatcherite paranoia with new British horror film Censor last month, it feels like video nasties are all the rage again.

The Video Recordings Act of 1984, for those uninformed, had made banned Italian exploitation classics Cannibal Holocaust, Zombie Flesh Eaters and Tenebrae – as well as British and American works like Norman J. Warren’s Inseminoid and Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead – notorious in 80s Britain. But by the end of the decade, these territories would find themselves out-nastied as Hong Kong filmmakers took advantage of their own new film classification system.

The Hong Kong motion picture rating system of 1988 had introduced three levels of age restrictions for film materials, with the strictest being Category III – which deemed a film unsuitable for anyone younger than 18 to view. The intention was to protect young people from being exposed to dangerous or unsuitable material. But in practice, the categorisation became a coveted brand signifying sex, violence and sordid thrills.

The wildest texts of the early 90s Category III heyday are intensely vivid in their depictions of brutality, borderline pornographic and, on occasions, outright offensive by modern standards. And yet even actors as esteemed as Hou Hsiao-hsien muse Shu Qi (Millennium Mambo, The Assassin) and Wong Kar-wai favourite Leslie Cheung (Days of Being Wild, Happy Together) made names for themselves with raunchy comedies like Viva Erotica. Either way, with the Hong Kong Handover looming on the horizon as 1997 approached, sparking fears of greater censorship under the authority of Mainland China, exploitation cinema boomed to the extent that up to 25 per cent of all films produced in Hong Kong in the 90s were branded Category III.

The Hong Kong film industry’s fears are now fully realised in 2021, with restrictive new legislation in the name of “national security” effectively requiring filmmakers to self-censor their works for fear of running afoul of the Mainland. But with UK distributors 88 Films reissuing three of the below Category III highlights in August and September 2021, Hong Kong’s exploitation boom of the 90s, at least, remains immortalised.

Viewer discretion is advised. But as a uniquely bizarre and consistently outrageous filmmaking movement – the likes that may never be witnessed again in Hong Kong – Category III exploitation movies remain the apex of east Asian extreme cinema. In 2021, this treasure trove of midnight movie madness remains ripe for latent discovery – for the strong-stomached, at least.

Erotic Ghost Story, 1990

This mystical, magical tale riffs on the plot of fantasy-comedy The Witches of Eastwick. Only instead of the idylls of Rhode Island, the three meddlesome maidens of Erotic Ghost Story roam a rural, and rather more sordid village in pre-modern China.

Colourfully dressed and romantically inclined, the sisterly trio spends much of the film pursuing a handsome young scholar who hides a fearsome secret. But first, a band of thugs are deceived as punishment for their wicked ways: an early highlight finds the women canoodling in the forest, only for the lucky men to suddenly realise that the women they are fornicating with are not beautiful young vixens, they’re decrepit, rotting corpses! From that moment onwards, Erotic Ghost Story offers a plethora of sexy delirium involving camp superpowers, acrobatic beat-downs, and naked flesh.

The film’s HK$10m box office success helped actress Amy Yip to become a Hong Kong sex symbol, with her raunchy reputation further cemented by exploitation flicks Robotrix and Sex and Zen (the highest-grossing Category III movie in Hong Kong box office history). Yip’s presence in the industry would be underlined by a distinctive legacy: the method of revealing the side of a woman’s breast in a camera shot becoming known henceforth as the “Yip tease.” In Singapore, meanwhile, countless fast-food restaurants still sell “Amy Yip bao”, named for their voluptuous size and soft, round shape.

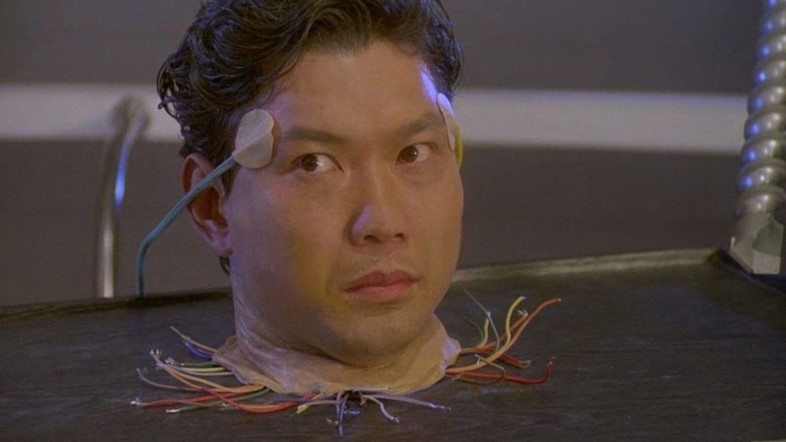

Robotrix, 1991

Ever watched Robocop and thought “this film needs much more sex”? Well, here’s the answer.

A blatant and brilliant imitation of the Paul Verhoeven classic that also liberally borrows set-pieces, characters and costumes from The Terminator, Robotrix concerns the rescue of a rich oil tycoon’s playboy son, who is kidnapped by a murderous cyborg. His only hope? Former minder and policewoman Selina Lin – who was herself murdered by the evil scientist-robot Ryuichi Yamamoto, only to have her consciousness transferred to a combat robot in the service of the police force.

This erotic Hong Kong sci-fi thriller is a pinnacle of cult Category III filmmaking. It’s frequently shoddy, relentlessly silly, and needlessly packed with sex. The raunchier scenes range from the disturbing (at one point, Ryuichi Yamamoto-bot is observed to shag his victims to death) to the hilarious – such as when a cop at a stakeout becomes so horny he disguises himself as a brothel client in order to sleep with a robot call girl. But for all titillating fodder, Robotrix is also a mindlessly enjoyable romp – full of insane fight scenes, imaginatively kooky set design, loopy performances and explosions.

Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky, 1991

Perhaps the greatest Hong Kong exploitation movie of all time, Riki-Oh, was nonetheless a disappointment at the box office upon release. But despite only grossing around one-fifth of what director Lam had accrued for Erotic Ghost Story, this brutal prison dystopia would go on to achieve cult status in the west, courtesy of word-of-mouth reputation for its ludicrously gory violence, over-the-top villains and atrocious dubbing into English.

In 2001 AD, as is revealed in the film’s opening exposition, everything from car parks to prisons have become franchised businesses. The bare-bones, concrete monolith that houses the film’s titular Ricky – sentenced to ten years for the killing of a crime lord – has subsequently become split into four factions, with each prison unit violently keeping the others in check. What ensues across the film’s 91 minutes of mayhem, then, is a fever dream of violent chaos: skull crushings, booby traps and gut-rupturing punches included.

The midnight movie appeal is best embodied by the character of Cyclops Dan, a hook-handed assistant prison warden whose office is lined with adult videos, and who keeps medicine to treat his obesity (or, in the English dub, mints) inside his glass eye. His bow-tied superior, simply named “the Warden”, on the other hand, resembles a manic, Hong Kong version of Roger Rabbit’s Judge Doom.

The film’s creative and overblown fatalities, meanwhile, have a legacy of their own – as a noted influence on the Mortal Kombat video game series, with the titular Ricky also closely resembling the fighter Liu Kang.

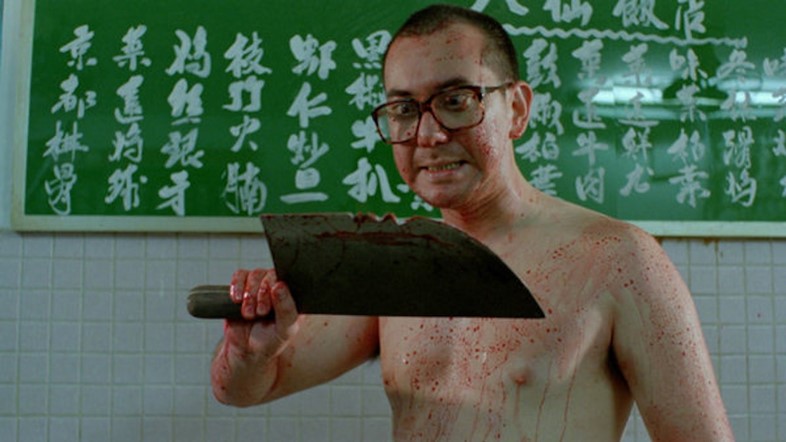

The Eight Immortals Restaurant: The Untold Story, 1993

A team of police are led to a restaurant after a bag of dismembered limbs washes up on a beach shore. Here, they learn that the former owner and his family have all mysteriously left the country without a trace – while new owner Wong Chi-hang (Anthony Wong) is accused of cheating at mah-jong to swindle his competitors out of cash. Could the two events be linked? Yes, they could. Because, as is revealed in a series of disturbing flashbacks, Chi-hang butchered the lot of them, and baked their cadavers into delicious char siu bao.

Incredibly, this morally depraved tale was not fiction, but a real-life murder case. And while the cannibalistic plot was taken from sensationalist rumours rather than fact, much of the narrative elsewhere remains remarkably true to the real-life monstrosities committed upon a family of ten in the Eight Immortals Restaurant in Macau, 1985.

The psychotic lead role is played by Anthony Wong –“the king of Category III films” (who, rather surprisingly, walked away from the Hong Kong Film Awards in 1994 with the Best Actor prize in hand). It would be the first of many for the actor, who subsequently became a staple of Hong Kong cinema after appearing opposite Chow Yun-Fat in John Woo’s Hard Boiled, and in Infernal Affairs (later remade in the US by Martin Scorsese as The Departed, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jack Nicholson).

Ebola Syndrome, 1996

After a rabid sex scene at the opening ends in a woman’s tongue being snipped off with scissors, serial rapist and murderer Kai San (Anthony Wong), flees to South Africa, where he encounters an indigenous tribe after being threatened by a cheetah. An attack on one of the tribal women results in Kai San contracting Ebola – a virus that “will gradually dissolve internal organs within 72 hours” of infection (though Kai San, for some reason, is immune). He then proceeds to murder his employer at a restaurant, packaging the remains as “African pork buns” as he becomes both viral super-spreader and Hong Kong Sweeney Todd.

Full of mindless sex, misogyny, violence, and negative racial stereotypes, Ebola Syndrome makes for horrific viewing in more ways than one. Accordingly, when the film was released on DVD in America, over 130 seconds of footage had to be cut – including 21 seconds of human autopsy and an extended take of Kai San being urinated on.

But the film remains a testament to director Herman Yau’s inexorable ambitions as a filmmaker. 24 years and 60-odd films later, Yau’s action thriller sequel Shock Wave 2 grossed a staggering US$226.4 million worldwide, ending 2020 as one of the ten highest-grossing films worldwide alongside the likes of Christopher Nolan’s Tenet.