Apichatpong Weerasethakul shares about the new table book that accompanies his Cannes Jury Prize-winning film Memoria, starring Tilda Swinton

For his latest spellbinding work, revered Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul took to Colombia with Tilda Swinton in tow – a meditative journey through which to process his experiences with a strange ailment that disrupted his sleep for years. The ensuing project would be titled Memoria, and after premiering as a film (his first in the English language) at Cannes, it took home the festival’s coveted Jury Prize in July 2021.

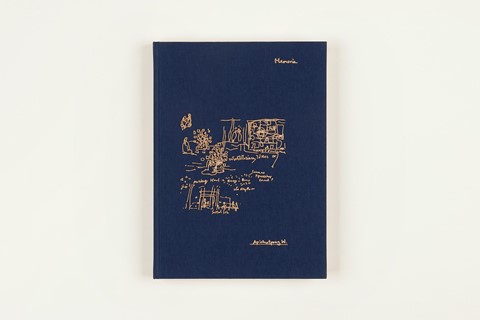

But the boundaries between cinema, art, philosophy and reality have always been blurred for Weerasethakul – and the captivating table book that accompanies Memoria (published by Fireflies Press this week in the UK) too, feels like something of a waking fantasy. “As I travelled, I have had many imaginary films in my head,” Weerasethakul tells AnOther via email, cryptically. “They are in this book.”

Weerasethakul is no stranger to the mysterious. Having grown up in the lush, humid environs of north-east Thailand – a country where 95 per cent of the population practices Buddhism – it’s no surprise that his delirious and visually resplendent work is steeped in introspection; a kind of lucid, slow cinema reminiscent of auteurs like Andrei Tarkovsky (Solaris) or Tsai Ming-liang (Goodbye, Dragon Inn). Built on elliptical structures, cinema verité photography and a rejection of traditional notions of genre and narrative form, his strange and complex films are weaved with elusive stories that are rarely confined to the images we see on the screen.

The languid and scorching Tropical Malady (2004), the Venice Golden Lion-nominated Syndromes and a Century (2006), and the Cannes Palme d’Or-winning Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) are defined by split characters, spiritual encounters and dual narratives that hint at subliminal meanings beyond the tangible. As such, it is fitting that Weerasethakul’s latest cinematic feat is supplanted by an extra-filmic entity itself. “The book is an expansion,” as he describes it, “to pinpoint the core of emotion I had of Colombia, and maybe of my world in general, at a time.”

In a letter to Tilda Swinton, recreated in the Memoria book, the director lays out the film’s brisk plot: “Jessica is troubled by the mysterious explosion in her head which makes her insomniac. She found a source of the sound [described as “like a rumble from the core of the Earth” by Swinton in the film’s trailer] in a small town in the middle of the country, through a man from outer space. Eventually, she manages to fall asleep. The End.”

But of course, there is more to Memoria than what can be revealed in a simple narrative. Weerasethakul reveals further layers to the project in the book’s introduction: “I was startled by the sound of an explosion. It was a bomb, at dawn, not from elsewhere but within my head … It feels like someone snapping a rubber band inside your skull.”

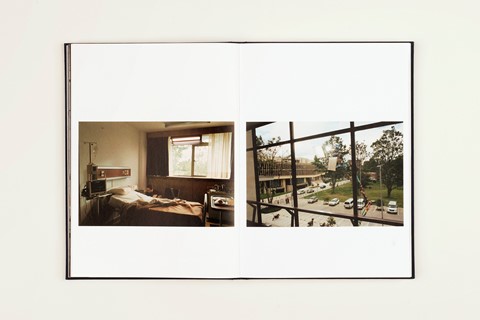

He is describing his experience of the strange condition known as Exploding Head Syndrome – a rare kind of parasomnia that can deprive the sufferer of sleep. “For years I usually woke up after three hours of sleep, fresh,” Weerasethakul continues. “Then I entered a ‘drifting’ stage in which scenarios came and went … The images were dim, as if they were in a stage of decay. Logic was not clearly understood. Time decelerated.”

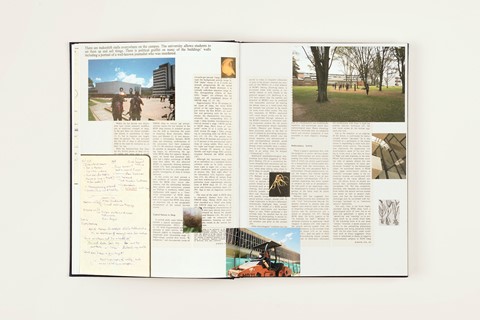

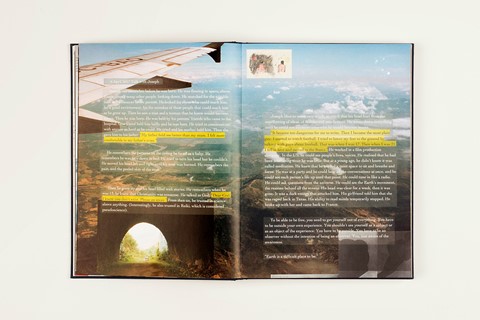

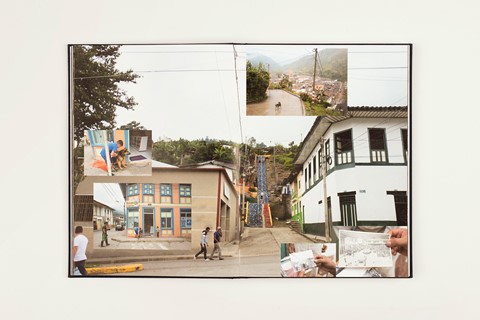

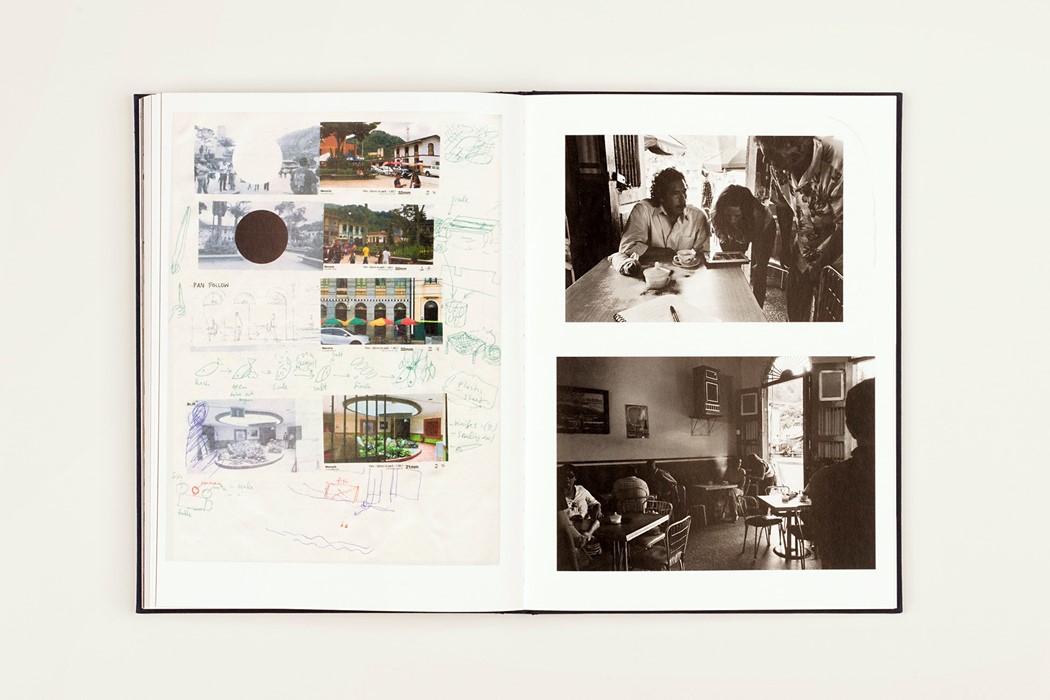

This waking dream-state mimics the nature and form of the Memoria book. A structureless montage of script notes, diary entries, hand-drawn illustrations and rich research photography that traverses archaeological sites in Bogotá and the verdant jungles of the South American countryside, it feels itself like a fractured stream of consciousness. Weerasethakul explains the book as “like a film in itself, with its [own] wealth of memory.”

The characters sporadically referenced within – via newspaper clippings and personal reflections – are strange. There’s “the woman who can’t forget”; Eduardo the “derelict cinema owner”; and Gustavo, the farmer turned treasure hunter who “saw a ghost in the forest at night … its footsteps like that of a very strong horse’s gallops”. They fill the rich landscapes of Colombia with mystery and intrigue.

Cryptic quotes and research notes, meanwhile, demand further speculation. “Is Mt Mantap Suffering from ‘Tired Mountain Syndrome?’” reads one headline – as text elsewhere on the page refers to underground nuclear tests in North Korea. A few pages later, over a vista of a mountainside village square, something more lyrical: “There is a large river and a small one that pass through the town. The river has a nice, soothing sound.”

Most striking, of course, are the glimpses of the country’s sumptuous tropical environments, vibrant towns, and cavernous underground caves (“I love the archaeology,” says Weerasethakul, “the research on the remains”). They almost look like a mirror for the director’s own country, 11,000 miles away on the opposite side of the planet. “The change of environment seems to be revitalising,” reads a diary entry that forms part of a lengthy bookend – as another duality reveals itself.

And revitalising this project clearly was. At the climax of Weerasethakul’s written introduction, the director reveals that “In Bogotá, and 300km away in Pijao, as I was making Memoria, the morning ‘bang’ [inside his head] disappeared. With it, the precious, murky, drifting realm was gone. For better or for worse, I could sleep for seven hours a night.”

In some ways then, the mystery of Memoria was vanquished without ever having revealed itself. But the meaning of the journey goes beyond such simple truths.

Memoria is published by Fireflies Press, and is available now.