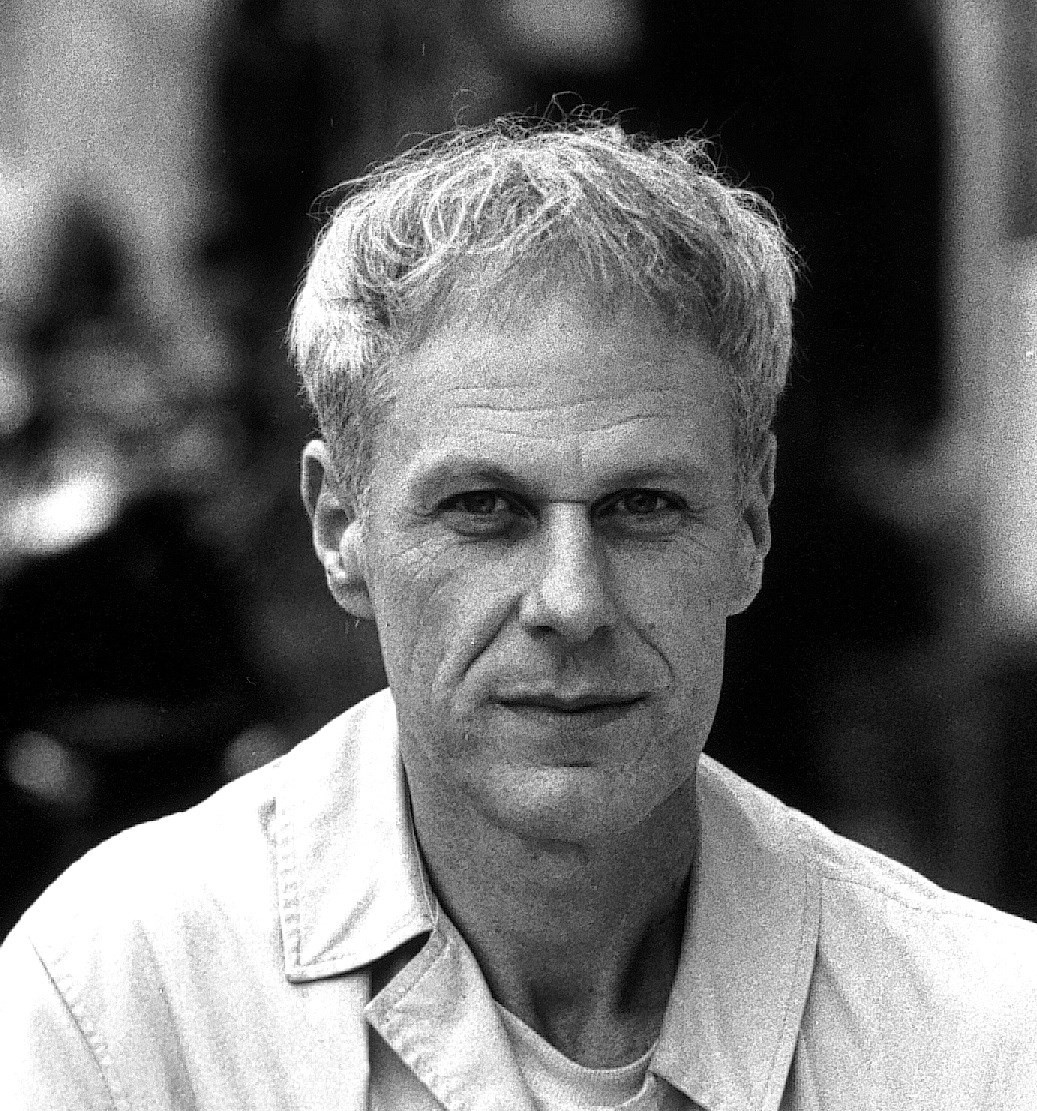

There are few writers like Dennis Cooper. To read his novels is to gaze into the bleakest depths of humanity and to come out the other side feeling utterly violated. What more could you want? Murder, rape, paedophilia, incest and castration are all constants throughout Cooper’s work and have led him to win praise from transgressive icons such as Kathy Acker and William Burroughs. The George Miles Cycle, his series of five interconnected novels published between 1989 and 2000, is a landmark of American literature and was inspired by his real-life friendship with a man named George Miles. Cooper has built a mythology around Miles in his work but with his latest novel, I Wished, it seems Cooper is finally ready to pull back the curtain on the legendary figure. I caught up with the author on a Monday afternoon as he sat and smoked in his Parisian apartment.

Barry Pierce: How would you describe I Wished?

Dennis Cooper: I guess it’s a novel by default, because it’s prose and it’s that length. It’s a novel because that allows me to not be factual all the time, because it’s not factual all the time. I don’t know what it is, people keep saying it’s autofiction but I have no relationship to whatever that is.

BP: It’s been over 20 years now since the George Miles Cycle ended, what made you want to revisit George?

DC: Well I had, for a really long time, wanted to write a novel that was about the real George Miles because the George Miles in the George Miles Cycle is not who he was. I used him as a template and [the novel] as a tribute to him and all that, but it didn’t really reflect who he really was as a person. I succeeded in making people very interested in George Miles, which is what I wanted, but at the same time I felt I should make clear who he really is. Also, he was just so important to me that I thought I should really force myself to deal with this because it’s a very difficult subject for me. I’ve never written a book that’s really, really personal like this before.

BP: I Wished is very much, by your own standards, a ‘tame’ narrative. It feels like you’ve pulled back a bit and shown your vulnerability because there have been Dennises in your previous novels but the Dennis in this one does truly feel like yourself.

DC: Well, I mean, it is me. Not everything in the book is completely factual, the novel keeps telling you that it’s not factual, but some of it is. I never talk about myself much, it’s not my natural inclination, I’m not driven to express myself in my work so I wanted to find a way where I could write a book where I could just explode my feelings and emotions out, but also be very aesthetically in control of it at the same time. I tried all kinds of different things and ended up with this strange sequence of tangential things that add up to being a tribute to George.

“[George Miles] was just so important to me that I thought I should really force myself to deal with this because it’s a very difficult subject for me” – Dennis Cooper

BP: When I was reading it, I don’t know if you agree or not, I found there was a sense of finality about it. As if the book were a coda to the Cycle, as if you were finally, truthfully, talking about George and saying “this is it.”

DC: I didn’t set out to do that, I understand that that’s how it reads and people keep saying that to me. I didn’t think of it really having an attachment to the Cycle. Obviously, I talk about the Cycle in it but I just wanted to write something about George and if you know the Cycle then that helps, but you don’t need to know the Cycle to understand the book. It’s a finale in the sense that I kinda wanted to ‘set the record straight’ or whatever they say. I understand why people say it’s a coda to the Cycle but I just wanted to write about George. And finality? I guess so, I don’t know. It’s not like finishing it made me not think about George anymore. George is somebody I’ll always think about and I’ll probably always write things that somehow came out of what I learned from him, but I don’t know, I think it’s too early to tell if there’s a finality or not.

BP: How do you view the Cycle now that it’s been 20 years since the final book was published?

DC: Well, I decided to write what ended up being the Cycle when I was a teenager. I wanted to write this big thing that would be multiple books. Everything I was doing up to the point where I started was kind of like trying to prepare myself to do it. You don’t think about your old work that much, people mention it but I’m more interested in what I’m doing now. But I’m proud of it, I think I’m a better writer now than I was when I wrote it, but I suppose people always say things like that. I spent ten years working on it but I don’t think of it as my crowning achievement or anything.

BP: So what was the initial reaction to the Cycle when it came out? I reread Frisk this week and it is kind of impossible to think of it coming out today. However, I feel that there is something about your work where you go so far, so deep into transgression, that you are practically untouchable. Uncancellable, even.

DC: Well, I was writing the Cycle in such a different context. It was a time when books like mine could be published by a major publisher, that wouldn’t happen now. I got really lucky because it was at a time when ‘gay fiction’ and ‘transgressive fiction’ were the big thing. Frisk, you mentioned, came out literally a month after American Psycho and a week after Jeffrey Dahmer got arrested, so it was in the middle of all this stuff. I got attacked, I got a death threat, [people] protested and all this stuff – it was quite intense. I always say this but there wasn’t openly queer films or openly queer television or openly queer music; people who were queer and who were cultural, they read novels. People were reading a lot more books then so you could write a book and it would have this ripple effect, because people actually cared about books. As much attention as Garth Greenwell or Ocean Vuong get, it’s not on the level it was back then.

BP: Do you think that truly transgressive literature still exists?

DC: There are people who are pushing the boundaries, there’s been a number of very out there, very explicit, violent, sexual books that have come out from small presses in the last few years and some of them are quite good.

BP: I think there’s a problem with a lot of contemporary queer literature. It’s all very sanitised and it’s all about quiet meditations and glances across the room. If there were a Dennis Cooper-type writer up and coming today you’d struggle to see where their writing would fit in the current queer literary landscape. It, realistically, could not exist in the way that it absolutely should.

DC: Well, there are people doing it but you really have to hunt them down. It’s just not getting very far and not reaching beyond a small group of people. You’d never even get buzz on the internet about it because for promoting that work you’d be attacked for promoting it. It’s not an easy time to be daring.

BP: Do you see our current time ending? Do you see everyone getting fed up with it and then we’ll see a great renaissance of degradation?

DC: [Laughs.]. I mean it’s definitely temporary, everything is. I don’t know whether to agree but I’m sure there’ll come a time when people will not become hysterical every time someone writes something that, like, triggers their childhood memories. People will become less tolerant of that and more like, “well, deal with your shit, this is literature.” Right now that’s tricky but of course it’ll change.

“Frisk ... came out literally a month after American Psycho and a week after Jeffrey Dahmer got arrested ... I got attacked, I got a death threat, [people] protested and all this stuff – it was quite intense” – Dennis Cooper

BP: Yeah, for that reason I think your books are currently more important than ever. I mean, to me at least, I have always felt that in degradation there is a great catharsis that I feel is good to explore. When I was reading through Frisk it sort of felt like taking a cold bath because I spend all day on Twitter and it’s absolutely manic and everything’s happening at once, so when I read everything that happens in Frisk, it almost feels good for you. Do you feel the same? I feel this might just be me, I may be deranged.

DC: My books are good for people, I like that. I mean it’s much the same as escaping into a movie theatre, isn’t it? I love reading and it’s for the reasons that you said. I do think it’s good for you, especially right now because there’s so much fucking noise. All these people who think everybody needs to hear what they think about everything, it’s so weird. So yeah, I guess I’m agreeing with you.

BP: I’ve been thinking about something a lot recently and it’s something that I thought, I really must get Dennis Cooper’s opinion on this, and it’s the fact that eating ass has now entirely replaced the term rimming.

DC: [Laughs.]. It’s true!

BP: What happened there? What happened to good old-fashioned rimming?

DC: Rimming seems too wussy now, I think. Rimming now is like, “oh you just licked the hole on the outside you didn’t shove your tongue in there and suck?” Eating ass sounds more violent and passionate. I have this blog and I collect these escort and slave posts and the language they use, they’d never say they want to be fucked; they want to be pounded, they want to get their ass destroyed. Destroy my hole! They say things like that. It just sounds better, it sounds more exciting, it’s like “ooh it would be fun to destroy a hole.”

I Wished by Dennis Cooper is published by Soho Press, and out on 14 September 2021.