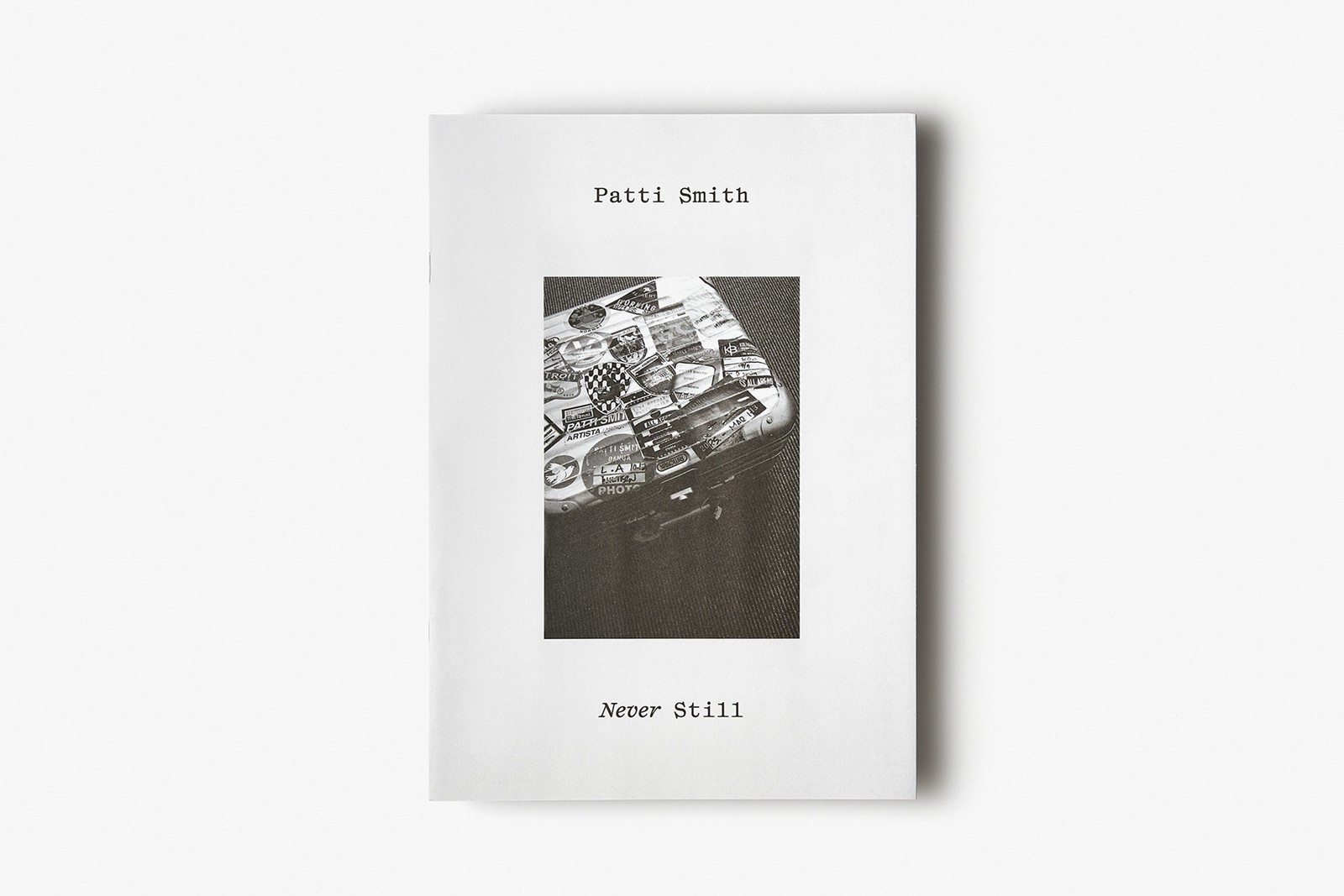

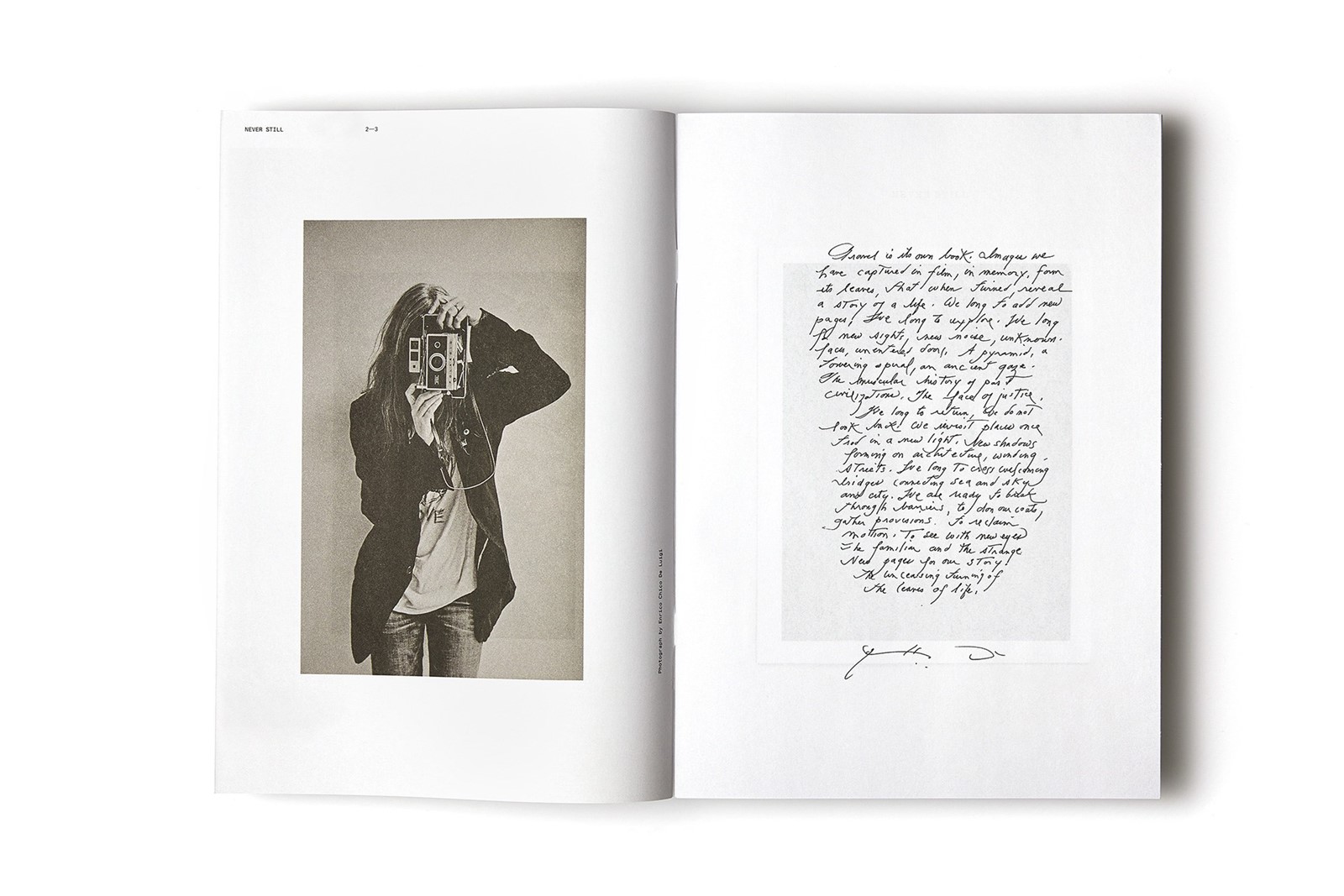

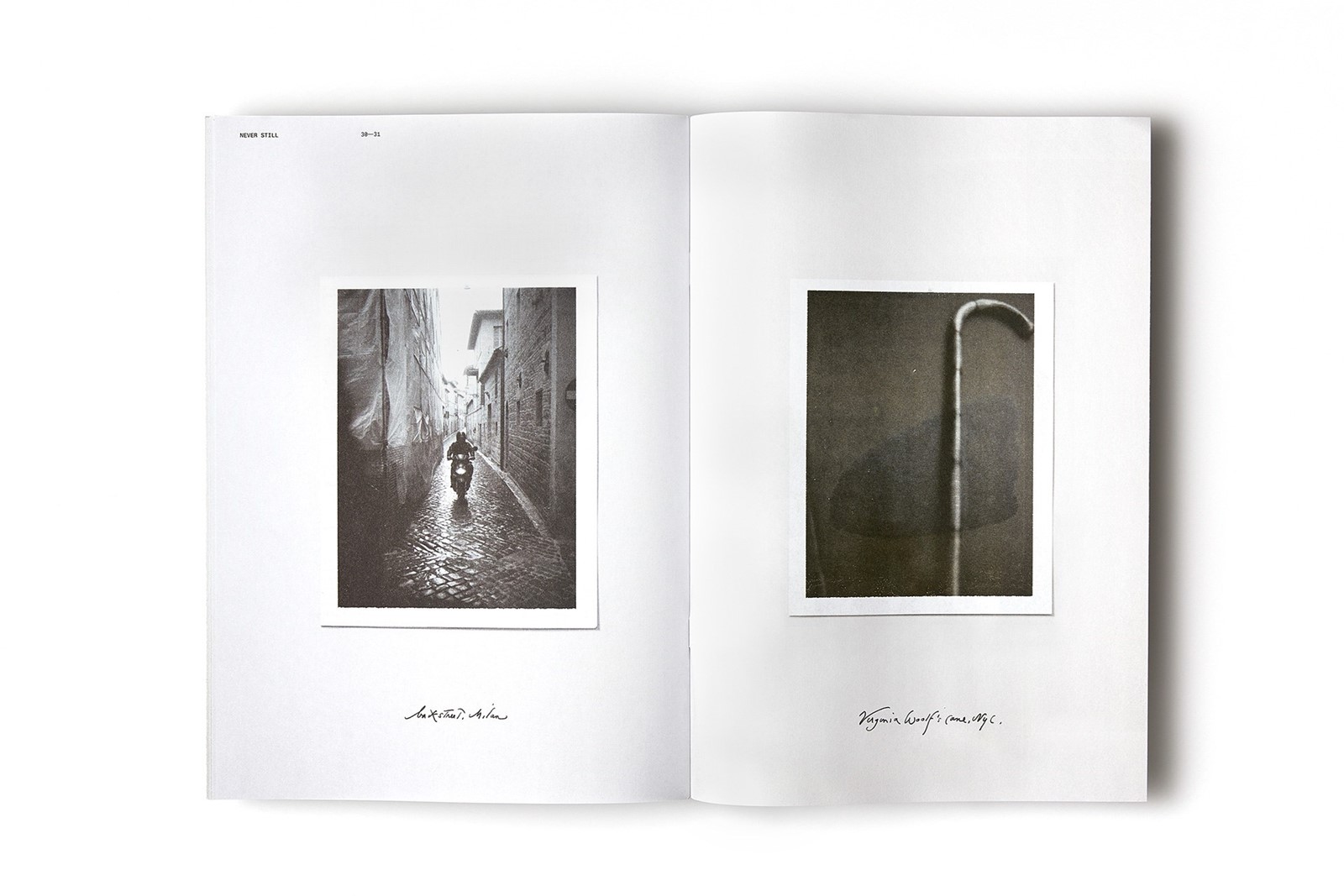

Enclosed within the pages of the latest issue of AnOther Magazine is a very special object: a unique artist’s booklet created with Patti Smith. This publication-within-a-publication features Never Still, a poem written by the preternaturally gifted polymath for RIMOWA in 2021 during a period of forced isolation and published here for the first time. Furthermore, this poem is illustrated with images selected and captured by Smith and accompanied by an intimate conversation with this magazine’s founder, Jefferson Hack, which expands on the themes and ideas held within the poem – themes such as travel: physical travel but also travel of the mind. This booklet is made possible by the support of RIMOWA, celebrating its new Never Still campaign in collaboration with Smith, who has been using RIMOWA luggage since 1995.

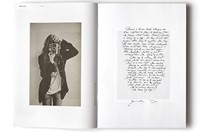

Here, alongside an extract from Smith’s conversation with Hack, we share an exclusive look inside this publication.

Jefferson Hack: I remember seeing a diary entry you posted on Instagram about all the plans you had for 2020 and it listed Vienna, London, Berlin, São Paulo. What did it feel like when all of that was cancelled?

Patti Smith: I had packed my little RIMOWA suitcase and the band was set to do a few dates on the west coast to ready ourselves for a world tour. I seem to have two very different sides of my personality. I’m quite reclusive, not very social. I like my solitude – that is probably the writer side of me. I am very adept at being by myself, working and travelling on my own. But when it comes to public life, I must project outward. I have to prepare myself for a lot of interaction, collaboration, sociability, being more open to people. I prepared myself like a boxer prepares and was about to enter a strong year of public life. I had packed my suitcase and was ready to go.

In early March we played two nights at the Fillmore West [in San Francisco], an historic venue that I love – everyone has played there from Jimi Hendrix to the Grateful Dead, the Doors, Big Brother and the Holding Co, Jefferson Airplane, all the great San Francisco bands. It’s a privilege to play there. Then we had a job in Seattle, and off to Australia. But when I woke up in Seattle and put the television on, the mayor was announcing, among several other sports events, that Patti Smith and her band at the State Theatre was cancelled. It’s so strange to turn on the television and see that your work is cancelled. And the phones started ringing and we had to pack immediately to go back home and quarantine for 14 days.

But afterwards, like everyone else, we unexpectedly went into full lockdown and I was suddenly alone in my room in New York City with my little suitcase, geared to greet the world, and had to completely turn everything around. Well, I accepted that. I know the history of pandemics and what’s expected of us. In the Fifties I went through serious quarantines as a child. I know how to take care of myself, how to cook and clean. I’m a writer and I know how to deal with solitude. But my big problem was that I had set my mind and blood for travelling, intense travelling, for almost a year.

Very quickly I felt like a caged animal. I love being alone in a hotel, alone in a cafe, but within motion. I love going from cafe to cafe, from country to country, from hotel to hotel. I don’t mind that kind of solitude, but this was rooted solitude that I hadn’t experienced since my children were young, and it was very challenging to dwell in this enforced rooted isolation. And believe me, I know that I’m very, very fortunate. I know that there are people all over the world who don’t have a solid roof over their heads, don’t have the safety or the options that I have. I’m not talking about it in any kind of complaining way. I’m just saying it’s a fact of my nature. You can take a wolf and put him in a luxurious palace and lock all the doors and windows and he’s not going to be a happy wolf. I just don’t like being confined.

JH: I wanted to talk to you about that idea of motion. Your poem Never Still is about movement, both physically and spiritually. You talked about the duality of your private and public selves but there is an energy in you that bridges both of those personalities, which is this idea of never being still – physically or spiritually. This idea of your mind, if not your body, constantly being on the move.

PS: For sure. I’m not an unrelaxed person, I just always have to be engaged in something. It’s true, I have an extremely active mind.

JH: You value time a lot – you make the most of every day, it seems, or you try to.

PS: That’s because I have enthusiasm, not only for my own work, which of course is paramount, but for the work of others. When I was a child, I loved books before I could read them. I loved them as objects. With each book we’re given world upon world, thanks to the imagination and labours of other people. I’m always reading or writing, thinking or plotting. I’m not a good meditator. I’m not the kind of person who empties out easily. I’m always filling in spaces because I’m writing or entertaining myself by imagining little stories or scenarios.

JH: What is your earliest memory of packing for a trip? And where was it to? Was it inspired by a literary journey?

PS: Funnily enough, we rarely travelled. My parents were very hard workers. My father worked in a factory, my mother was a waitress. They had four children after the second world war. We lived on shoestring means and we rarely went anywhere. I never went to camp. I didn’t see a museum until I was 12. And that was a short journey from New Jersey to Philadelphia – my father didn’t have a car, so to take six of us on a bus was a big expense. But that trip, seeing art in person, discovering Picasso, was life-changing. In terms of packing, the first time I really packed up was at 20, when I left home.

JH: Can you recollect leaving the factory job, leaving the town you lived in and heading to New York City to fulfil your mission?

PS: I can remember it exactly. I always wanted to travel, since I was a little girl, seeing pictures in libraries of foreign places. Images of pagodas, the Taj Mahal, palm trees, pyramids. I wanted to see all these things. And where I came from, a very rural area of South Jersey, people really didn’t travel. No one had passports. No one thought of going to Europe. They didn’t even go to New York City, which was only two hours away. When I grew up in the Fifties and Sixties, people didn’t crave travel, they craved stability. But it was after the second world war – people wanted to be home. They wanted to start a new life. They weren’t interested in travel. And all I used to think about was seeing the world. I wanted to go to Tibet. I wanted to go to Paris.

In the summer of 1967 my options in South Jersey were spent. I got laid off from the factory, I couldn’t find another job. I went to New York City first of all to find a job, preferably in a bookstore. I had a little plaid suitcase – brown and yellow. And I just packed a few belongings and my copy of Illuminations [by Arthur Rimbaud] and a few talismans, and pictures of my siblings. I had about seven or eight dollars and I said goodbye.

I didn’t know where I was going to stay. I didn’t have money for a hotel. I got a one-way ticket, but when I hit the street with my little suitcase I didn’t feel a shred of fear. I felt freedom. I felt the same freedom as a ten-year-old racing through a field or falling asleep in the woods. I just felt free. I felt that sense of going to a new place, not just to see what the new place will give you, but to get a sense of possibilities. People often say, “Well, weren’t you afraid? Weren’t you afraid to sleep in a graveyard? Or in the subway?” But I really wasn’t.

JH: Where did you sleep that first night?

PS: It was summer. I went in search of some friends who I hoped would put me up for a night, but because they didn’t have telephones, I just showed up and knocked on their door. My friends had moved out of that apartment, some other fellow had it. He told me to go ask his roommate and see if he could tell me where my friends had moved to. That’s when I first saw Robert Mapplethorpe. He was sleeping and woke up and smiled at me. I asked him if he knew my friends. He walked with me for a couple of blocks, showed me where they lived and then said goodbye. But my friends weren’t there either. I had forgotten it was a holiday and thought I’d just wait for them. They lived in an old brownstone with a wide stoop and a big entrance, almost like a little hallway. I just sat there with my suitcase and eventually I fell asleep.

I was woken the next morning by little explosions at the bottom of the steps. Some kids were throwing firecrackers because it was the Fourth of July. I woke up on Independence Day, having slept all night on somebody’s stoop, and that was my first night alone in New York City.

JH: What was it like for you, walking in an almost-empty New York City during the past year? You were wandering the streets and taking pictures and rediscovering the city without all of that life and energy.

PS: Well, at first there was an eeriness that I liked – there was very little traffic and the city was quite empty. It reminded me of the New York I knew when I was young. Like in 1967, when I first came to the city, when New York was almost bankrupt. During the pandemic, the streets were empty, sometimes the trash wasn’t picked up and there were more rats than there had been in a long time. And a lot of homeless people. It was very reminiscent of the past.

JH: There was this sense that people were rediscovering their own neighbourhoods. Perhaps travel can be as much about the local experience, looking at our immediate surroundings with fresh eyes and a fresh perspective, as it is about going to far-flung lands ... But I’d love to talk to you about dreams. Have you had any recent poignant dreams? Maybe of travel?

PS: My dreams this past year haven’t been so much about places, but other places in time. Because I’ve been rooted, I’ve been much more conscious of the people who aren’t here. Having lost my husband, Robert, Sam Shepard, my parents – an endless amount of people who were my world – I can invent new worlds as I travel. But as I was here, I felt the renewed melancholy of the loss of all these people. And especially Sam, because in recent years I could really count on him. He was so accessible, and I knew him for 50 years, and I expected that we would know each other for ever.

This booklet is featured in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which is on sale now. Head here to purchase a copy.