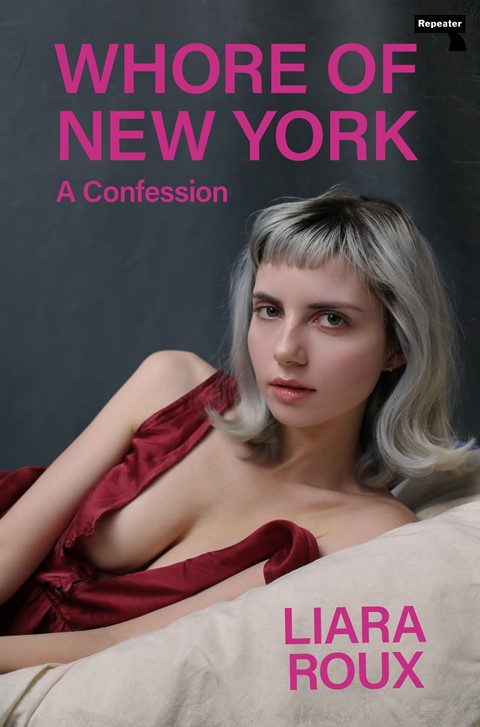

The author, sex worker and activist reflects on her first book, Whore Of New York – a sprawling study of capitalism, trauma and the contemporary sex industry

“Sometimes I feel guilty for how much I enjoy my work,” writes author and sex worker Liara Roux in the opening pages of her debut memoir, Whore Of New York. Likening herself to a “first-class pampered pet”, she then starts to reel off the perks of her chosen career. There’s the “diet full of Michelin stars”, the wardrobe of cashmere and silk, and the cross-continental trips on private jets. In later chapters, there are mentions of lavish shopping sprees and luxury hotels, as well as liaisons with bestselling novelists and kinky celebrity chefs. It’s the glamour you’ve come to expect from stories of the high-class, “happy hooker” archetype. Until it isn’t.

In reality, Roux’s debut is much more than just an enthusiastic defence of sex work. There are moments of enchantment, of course, but also despair: the clients who turn dangerous, the vomit-inducing exhaustion, and some viscerally repulsive descriptions of poor penile hygiene. There’s also the political context, which looms like a menacing shadow over all its pages. Roux may occasionally have difficult clients, but the stigma around sex work, and the restrictions placed on her by the state, are perhaps the things that wear her down the most.

Beyond all the sex work, there’s also the story of Roux herself. Whore Of New York is a memoir, above all else, and she is determined to paint as varied and profound a portrait as she can. She talks in detail about her upbringing; her troubled experiences with abuse, chronic illness, neurodivergence, misogyny, and frenzied back-and-forths to the psychiatrists. At times the book can be tangential – an outpouring of righteous frustration – with intermittent blasts of cultural criticism (Roux is staunchly anti-capitalist, with an anarchic love of pleasure, philosophy and psilocybin). On the week of the book‘s release, we caught up with Roux to find out more about why these digressions were so vital, and what she hopes readers will take away.

Dominique Sisley: This book straddles a lot of genres: it’s part memoir, part anti-capitalist critique, part defence of sex work, part philosophy treatise. When you first started writing it, what did you want it to be?

Liara Roux: I wanted it to be a really cohesive, full explanation of what drew me to sex work, and why I made the choice to do it so that people could really make their own judgments. I wanted to provide as honest a telling as possible because I think it can be really hard to find a story about sex work that doesn’t glamorise or demonise it in some way. And I hoped that, by providing my random thoughts about cultural criticism, and stories from my childhood that were very formative, it would provide a larger context for people to understand my choice.

DS: How does it feel to release something so personal?

LR: It’s definitely very intense. The idea of accidentally hurting or harming anyone mentioned in the book was like my greatest nightmare, so I tried to do my best to obscure everyone’s identities, as well as all the details and locations.

DS: Early on in the book, you refer to yourself as a “self-indulgent whore” and say that you feel guilty about how much you enjoy your work. Can we unpick that? Why do you feel guilty?

LR: That was hyperbole. I don’t feel too guilty. I thought that if I put it that way it would piss off all the right people.

“I think that most wealthy people are hoarders, but because they have so much power and influence, it’s not categorised as an extreme mental illness” – Liara Roux

DS: But you write about being exposed to a lot of bourgeois luxury, and a lot of very wealthy, hyper-capitalist people. I know we shouldn’t conflate capitalism with luxury, but did the extremity of all that wealth ever make you feel uncomfortable?

LR: I’ve spent certain periods of my life not having access to money, but still having access to very nice things. I never had a “rags to riches” story: I had a period where I didn’t have much money, but there were never any rags. I was always dressed in designer clothes – I would just thrift them. But I think there is, unfortunately, an uneven distribution of beautiful things. I think that most wealthy people are hoarders, but because they have so much power and influence, it’s not categorised as an extreme mental illness. I think it often stems from childhood trauma: if you look at a lot of people who are extraordinarily wealthy, they often have daddy issues, you know? With a lot of these men, their fathers were quite mean to them in some way. And I think capitalism was an interesting experiment, but I think it’s proven to be a remarkably inefficient system for distributing food and shelter to all the people who need and deserve it. I think we all deserve food, shelter and beautiful, fun things. Like, who doesn’t? Who shouldn’t have a nice life?

I do think we are facing interesting challenges, grappling with the ecological effects of consumerism and unbridled capitalism. But I’m foolishly optimistic, and have faith that humanity will figure out a better way of distributing all the wealth that we have. Because having seen just how much certain wealthy people have, it’s hard for me to believe that there isn’t enough.

DS: Oh yeah, you must really see it.

LR: Sometimes it’s just so absurd and obscene. I see [my client’s property portfolios] and I’m like, oh my god, you could house so many people in just one of your vacation homes. There are so many empty homes in America – especially in New York, where there are all these beautiful, luxury apartments clad in marble, with no one living in them. It just feels so inefficient. Like, why do you need to have all these beautiful works of art in your storage unit that you never even look at? Why do you need to have 12 houses that you never visit and you’re just holding for value, or think that you’ll visit one day but you’re a workaholic so you never do? I think it’s really a tragedy.

DS: You write a lot about the misogyny you’ve experienced and some of it is really shocking. How has sex work affected your relationship with men, or however you want to categorize that kind of toxic, patriarchal masculine energy?

LR: At the height of my sex work, when I was really burnt out, it was so hard for me to interact with men at all. I was working so much, and so often having frustrating, boundary-pushing experiences, that it was really hard for me to not feel triggered by any older white man, regardless of their intentions. But I think sex work also forced me to confront just how many men are traumatised by the patriarchy, and what society expects of them. There was a lot of fear about being vulnerable. For example, a shocking amount of my older clients had experiences of being hit every time they cried. It really would break my heart, because it‘s such an intense trauma to go through. It teaches people not to open up about their feelings, not to share things with women. But I think hopefully men are well on their way to being able to talk about their feelings in a more smart and adjusted way. I was actually talking with a friend recently about how so many of the men we know are more hysterical, in the whole sense of the term, than most of the women we know, because they’re finally un-repressing.

“I think sex work forced me to confront just how many men are traumatised by what society expects of them. There was a lot of fear about being vulnerable”

DS: You say in the book that, while the sex itself is not emotional, the work itself can be very emotionally draining. What do you mean by that?

LR: The sex itself feels very much like physical labour to me. But I think the emotional work of talking and dealing with clients, as well as the judgments from society, all make the work a lot more emotional than it would be otherwise. I think the type of work I do, especially, where it’s often longer bookings and I spend a lot of time talking to people, becomes a very intimate thing that can either feel emotionally intense or very therapeutic.

DS: Would you call it a healing profession? Do you see yourself as a care worker?

LR: Sometimes, yeah. Sometimes I definitely feel like an entertainment worker. And then sometimes I feel like a therapist, or it feels like really intense spiritual work. It’s really about how the clients approach me, it’s always such an individual thing … I write in the book, too, that everyone’s experience doing sex work is unique. I have a lot of friends who had a much better time doing sex work than me, and also friends who had a much worse time. I don’t think my experience is typical, but I do hope that it provides some light.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Whore Of New York: A Confession is published by Repeater Books, and available now.