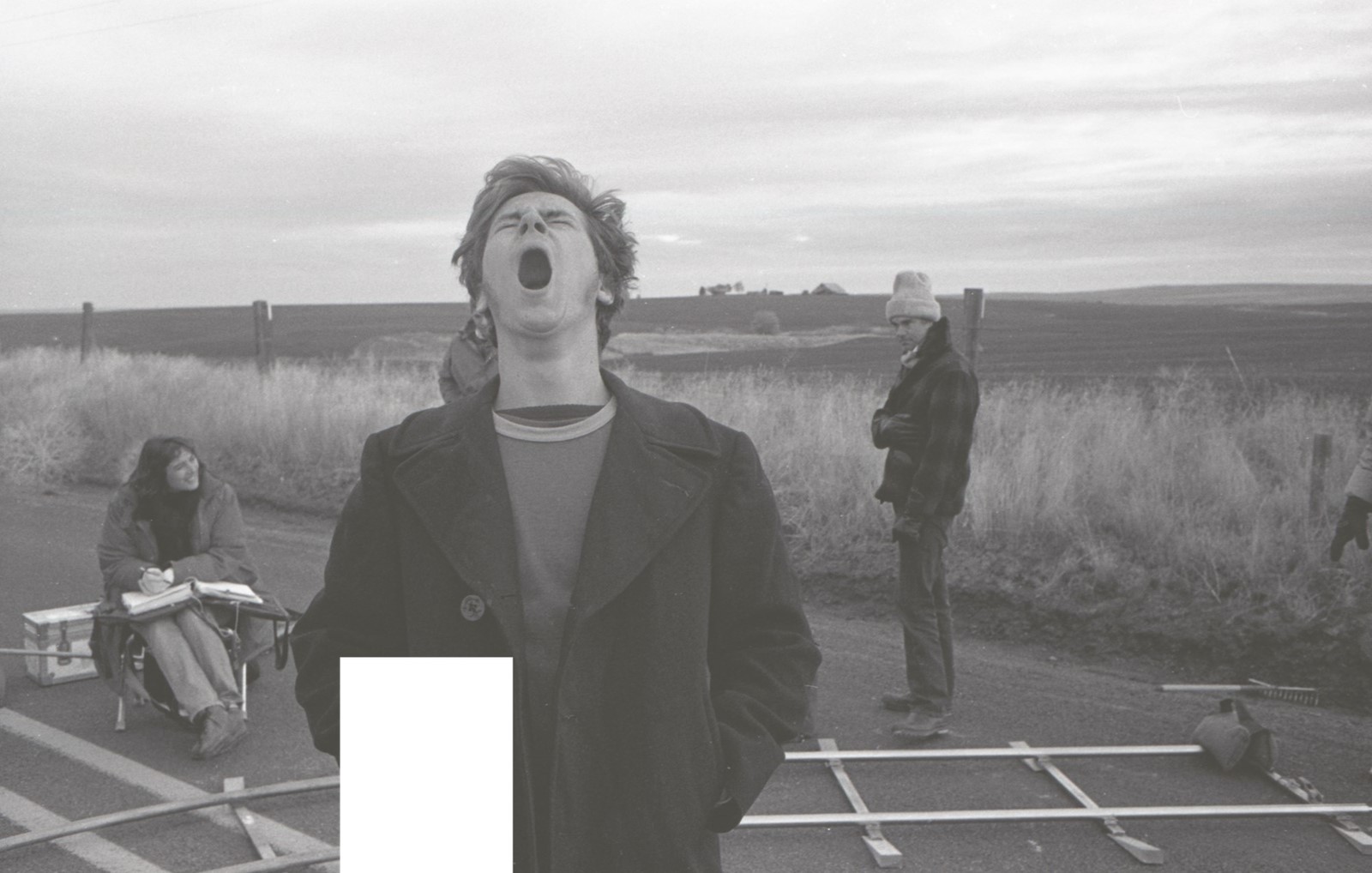

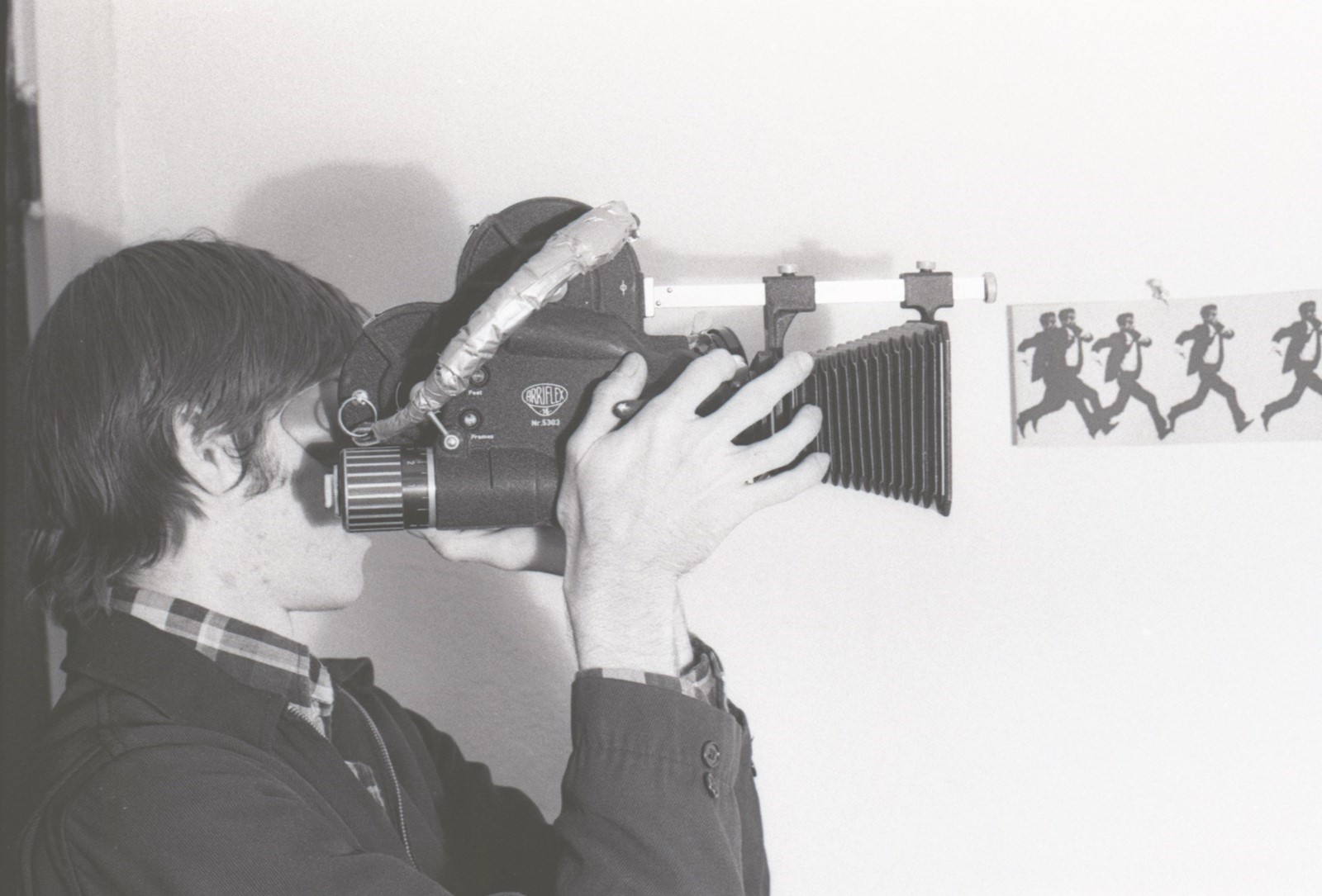

Gus Van Sant is a director who has never forgotten his independent roots. When not helming multi-awarding winning studio pictures such as Good Will Hunting (1997) and Milk (2008), he spends his time working with the wholly amateur casts of Elephant (2003) and Paranoid Park (2007). Preferring to rely on rough outlines of scenes and the natural improvisational talents of his actors, Van Sant’s films are characterised by a certain verisimilitude exuded by his characters’ actions and dialogue that no screenplay could truly replicate.

In a new book by art writer Katya Tylevich – titled Gus Van Sant: The Art of Making Movies – fans get a chance to glance back over Van Sant’s vast oeuvre and hear about the creation of each film from the perspective of the man himself. To coincide with the release, we caught up with Van Sant over the phone to discuss the new book, his influences, and the risks he takes as one of the most essential directors of the past 40 years.

Barry Pierce: The book is essentially a retrospective of your career up to the present day. What enticed you to such a project?

Gus Van Sant: Well, I had a call from Katya and I had seen one of the other pieces she did, a book about a few artists which I liked a lot, so I was like, yeah sure! [Laughs.] I’ll be the subject of a book.

BP: It’s quite an interesting book because it covers not only your filmography but also your artistic output, your paintings and your photography.

GVS: I was allowing [Katya] to go wherever she wanted to go, I wasn’t trying to guide her in the creation. I think because she was, in her past writings, doing things about art that it would naturally include my art.

“When you don’t have a script, all of a sudden your speech patterns become natural. You’re going forward without a flashlight” – Gus Van Sant

BP: There is a part in the book where you mention that one of your earliest influences in film was John Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972). What was it about that film that opened your eyes to filmmaking?

GVS: Well, at the time Pink Flamingos came out I was in the middle of art school as a film major. At that school I knew a couple of students who had been at the Maryland Institute College of Art where John Waters and a lot of the people in Pink Flamingos had also been. My attraction to Pink Flamingos was mostly because I had heard it was done just by a small group in Baltimore – the budget was something like $10,000 – but it was attracting so much attention. It was living proof that you could operate outside the system. So I went down to New York and saw it at the Quad cinema near 8th Street, near the Village. It was like Rocky Horror Picture Show; a lot of people in the audience seemed like they had all seen it before. When things happened – like when Edie the Egg Lady appears in the crib in the living room – the audience just lost it, but they obviously knew what was coming. It was very inspirational, the wild abandon with which John Waters was creating his film and the storyline and the mixture of characters were as extreme as you could get. It went off the charts.

BP: You had quite a difficult journey into filmmaking, you made your first feature out of your own money and it failed. How do you look back at that time now?

GVS: Yeah, I made a feature in Hollywood in 1978, I think, and it didn’t really fit together – the story, the writing, the execution and the concepts. It was called Alice in Hollywood and it was shot on Hollywood Boulevard with a group of different characters that I knew. It didn’t get into any festivals and I put it aside eventually and started working on the next thing. I wanted to keep going and not just stall out because of the performance of that film. I remember showing it in New York, it was on a videotape cartridge, and we had a little party for the movie but it was in a location where one room was the screen, and then there was a room next door where all the drinks were. Slowly everybody migrated to the room with the drinks while the movie kept showing on its own [Laughs.].

BP: You cast William S. Burroughs in both Drugstore Cowboy (1989) and Even Cowgirls Get The Blues (1993). What was it like working with such an influential, countercultural figure?

GVS: Well, Burroughs had been away and then he came back to New York in the mid-70s and he was seeing something of a revival. There was a lot of interest in Naked Lunch at the time. Some friends of mine were talking about it, and that was when I first learned about him and how he appeared in a number of the Kerouac books. So, I was in New York at one point and I looked in the phonebook in 1975, and he was there. His address was there as well. William S. Burroughs. I was like, holy shit! So I called him and he said to come over after Christmas. We spent like an hour and a half talking about all kinds of things and he gave me numbers of people to call up in LA, because I had just moved there, and was really helpful. Then, 15 years later, when I was doing Drugstore Cowboy, there was a character called Old Tom in it and he was perfect for it. So I called him up and he wanted to do it. But he made us promise that we shoot everything in one day, which we did. We did it all in one day.

BP: In Drugstore Cowboy and in My Own Private Idaho (1991) you broke from the convention of the traditional screenplay and instead used these barebones outlines of scripts – often just minimalist descriptions of scenes, with very little concrete dialogue. What attracted you to such a risky way of filmmaking?

GVS: I think it’s just something that happens on the set naturally. I think it started with Drugstore Cowboy. Kelly Lynch and James LeGros were in communication with the real people who appeared in the original book, so they were getting all of this information that wasn’t in the original screenplay or the book. We tried to incorporate these things into the film, and I liked that a lot better. When you don’t have a script, all of a sudden your speech patterns become natural. You’re going forward without a flashlight. When you have a script, there’s a lot of energy that goes into remembering what the script is. A lot of My Own Private Idaho was very loose, by then I didn’t care if the characters did the script or not. Gerry (2002) was the first film where I didn’t have a script at all, and we didn’t have much dialogue in that film either. Elephant (2003) was done in a similar way where the script was maybe about 15 pages of descriptions of what the scene was supposed to be and then everything else, if there was dialogue, became an addition to it.

“At this point in our cinema history, a documentary has as much fake stuff as a dramatic film, and a dramatic film has as much real stuff as a documentary” – Gus Van Sant

BP: Elephant, which was the film that won you the Palme d’Or, is described in the book as your most constantly relevant film. Why do you think that is?

GVS: Well, I’m sure because of all the shootings. Columbine happened before we shot Gerry and that became one of these mega-journalist stories, much like the death of Kurt Cobain, which was the film I did after Elephant. In both Columbine and Kurt’s news cycles there was this element of psychological investigation. What happened to Kurt? What happened in Columbine? And because of protocol around taste, there was no room for a dramatic representation or a dramatic investigation. And I thought at this point in our cinema history, a documentary has as much fake stuff as a dramatic film and a dramatic film has as much real stuff as a documentary. I had a problem with the vibe that you weren’t allowed to make a dramatic film about this subject at this moment. We met Colin Callender who had worked at the BBC [when they aired] Alan Clarke’s movie Elephant, which was about the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and it was at the height of the actual problem and it was aired on the BBC. So he had seen a project like this happen, so he referred to our project as “Elephant”. He said he couldn’t call it Columbine, as it was too hot an issue, so we called it Elephant.

BP: I want to finish off by talking about something that’s been happening online recently, which is the resurrection of To Die For (1995), even though the film was critically lauded upon its release, it is going through this great rediscovery cycle at the moment.

GVS: Wow, I didn’t know that.

BP: Yeah it appears quite often on my Twitter timeline. What do you think about it flourishing like this, decades later?

GVS: Well I saw that happen with Idaho. But I didn’t know it was happening with To Die For. It’s great, it’s fantastic, you’re always worrying about your film disappearing into the past but if there’s a new audience, it’s fantastic. It’s a very cool thing that’s happening.

BP: It’s one of Nicole’s greatest performances.

GVS: Yeah I’ve always heard that and it’s true. She really put everything into it. She’s amazing in it.

Gus Van Sant: The Art of Making Movies by Katya Tylevich is out now from Laurence King Publishing.