As a new documentary about Ailey is released, director Jamila Wignot sheds light on the visionary American dancer and choreographer, and the filmmaking process

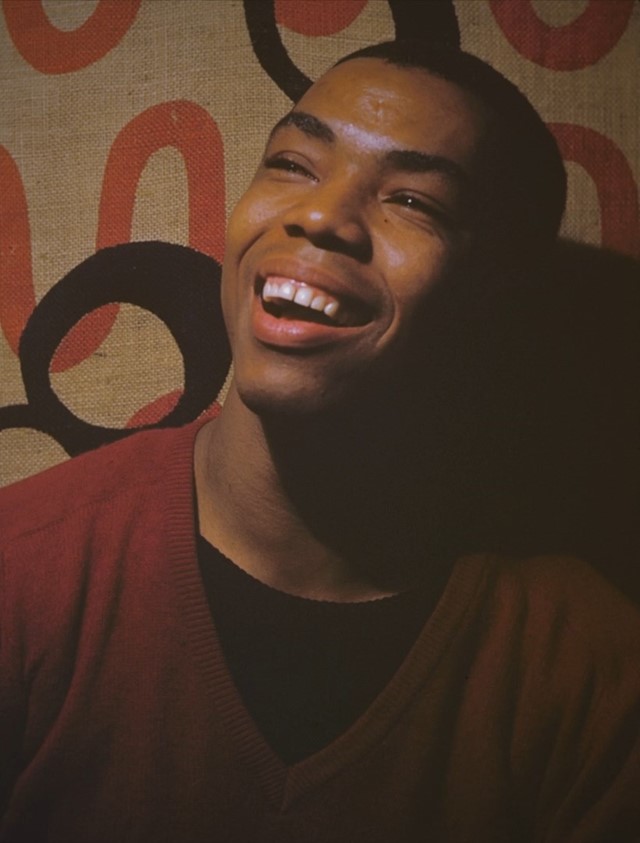

“I feel like I fell in love with him,” says director Jamila Wignot of choreographer Alvin Ailey, the subject of her mesmerising new documentary, Ailey. “And I don’t know if that’s always the best mode to take as a documentarian but I see this film as really a portrait and a love letter to somebody.”

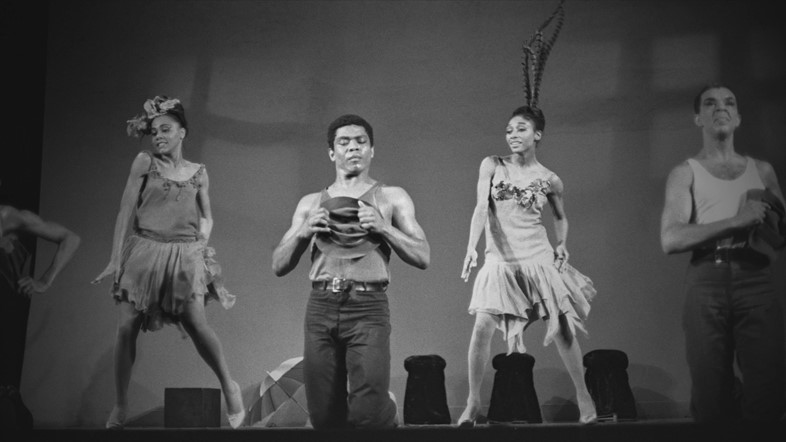

That love shines through the entire 82-minute running time – through Wignot’s sensitive, artful direction as much as in the voices of everyone who worked with and knew the visionary choreographer. It also infuses the euphoric footage of Ailey dancing, and in the rehearsal scenes of Rennie Harris’s 2018 ballet homage to him, Lazarus.

Ailey’s enormous contribution to contemporary dance, and his marriage of dance with civil rights activism, made him a star and an inspiration both in the US and abroad. Yet as Wignot’s beautiful film shows, Ailey himself was a profoundly elusive subject, one whose body and soul were in constant movement – a performer used to being centre stage but whose interior life was veiled even to those closest to him. There was a part of him, says Wignot, that “remained a mystery”.

Composed of numerous public interviews and gorgeous archive footage – in particular of Revelations, Ailey’s exquisite 1960 celebration of African-American heritage – Wignot’s film is underscored by previously unaired recordings of Ailey speaking to writer A. Peter Bailey in the last year of his life (Ailey died of Aids-related illness at just 58, screening his diagnosis from the public and even from his mother). Those tapes brought home to Wignot Ailey’s “incredible poetry”. It also provided her with deeper access to her intensely private subject.

“We had a good amount of his public speaking, interviews he had done on radio and television. And he’s wonderful and charismatic, but there’s a kind of performance in them,” she says. The audio, on the other hand, has the feel of an intimate conversation, especially where Ailey discusses his bipolar disorder, which he was diagnosed with only in his late 40s after suffering a breakdown, and two important relationships. His words gave Wignot a route into understanding the origins and meaning of his dance work, “because there’s a real kind of sensuality in his language, and a real sense of his surroundings, a kind of earthiness that’s there. And then at the same time, this incredible vulnerability, a deep insecurity, a sense of the real loneliness that was there.”

Born in Texas in 1931, Ailey had a hard-scrabble childhood, navigating the Depression and the violence and injustice of Jim Crow alongside his mother, who kept her and her son afloat by doing domestic work. Coming to dance in his late teens was a revelation, a joyful expression of self and a discovery of his innate talent.

His ballets – among them Revelations and Cry, dedicated to his beloved mother Lula Elizabeth – reflect and elevate Black experience and especially the experience of Black women. The film foregrounds the importance of women to Ailey throughout his life, whether it was his mother, early dance inspiration Katherine Dunham or Joyce Trisler, to whom he composed the ballet Memoria after her death. “He was very much formed by a kind of glamorous and domineering mother,” says Wignot, and that in life he seemed to have been drawn to women who replicated that dynamic.

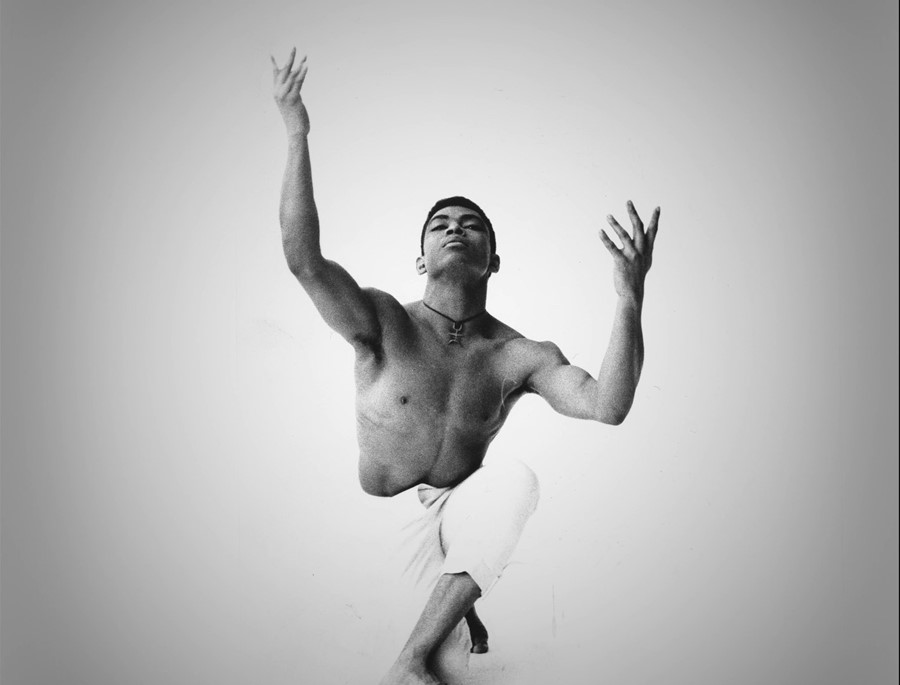

The film is also notable for its virtuosic handling of dance footage. For research, Wignot watched a lot of musicals, from West Side Story, to Fiddler on the Roof and Singin’ in the Rain. Some of the most magical moments in the film are those of Ailey or his dancers in motion. Repeated throughout is a sequence from Revelations of the dancers bowing their heads in formation and slowly raising their arms, a breathtaking image that feels as if they are about to take flight.

Some of Wignot’s favourite footage is of Ailey dancing as a young man clearly in love with his artistic medium. “I really think it was a salvation because everything (could come) pouring through his body in ways that I think he couldn’t access in everyday life.”

Though Ailey was beset by struggles – with his mental health, forming intimate relationships and keeping his sexuality private from the public, as well as the demands of fame and feeling the pressure as a Black man to be a paragon of the community – his evident joy in movement is infectious. The film’s emotional end is a testament not just to Ailey’s enduring influence but to the powerful effect he had on people in his lifetime and since. “We allowed (dancer) Judith Jamison to take the lead in on it in the film, but every person I interviewed had that story about (how), ‘Oh, God, he looked at me, and he found this thing in me, and he made the dance that unlocked who I was,’” says Wignot. Among the many beautiful experiences she had while working on the project was screening the film at the Lincoln Center in New York with Sylvia Waters, former principal dancer and now artistic director emerita of the company Ailey II. When the lights came up, Wignot recalls that Waters was in tears. “She said, ‘I’ve seen the film before on my laptop, but now seeing it (as a) theatrical experience – it’s just really overwhelming to be back with him.’”

Ailey is in cinemas now.