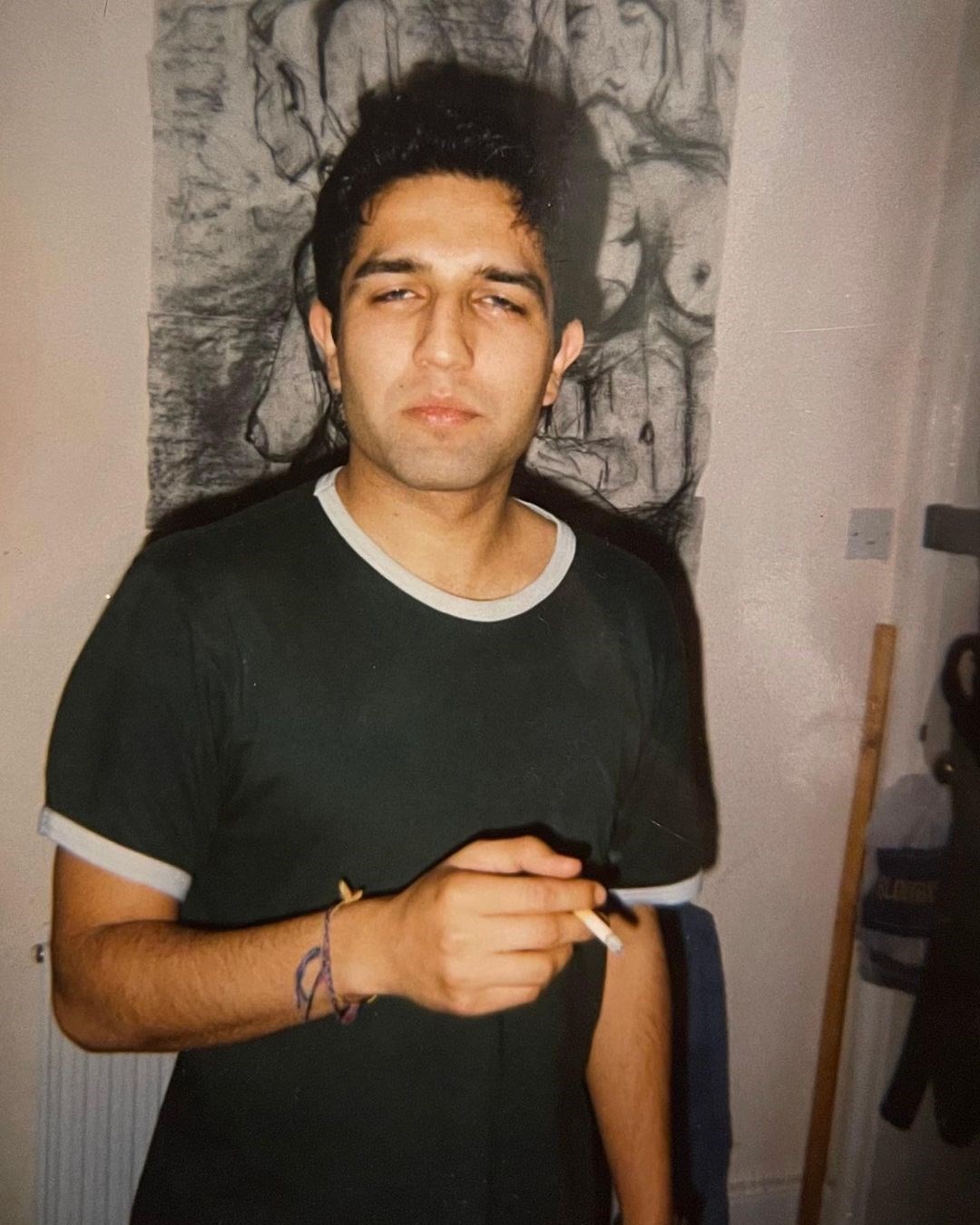

Many people will know Osman Yousefzada as a designer, who has shown for many years as part of London Fashion Week, or as an artist, who has created large-scale outdoor installations. But from now on, people will know him as a writer, too; as the author of the coming-of-age story titled The Go-Between: A Portrait of Growing Up Between Different Worlds, released last month.

Written from Yousefzada’s own perspective, the book details his memories growing up in a Pashtun community in the middle of a red-light district in Birmingham during the 80s and 90s. We follow him as he goes – as the title suggests – between different, hidden worlds; between the male and female spaces inside his own home, between the Pashtun and English spaces, and the Muslim and secular spaces outside of it.

Yousefzada paints a vivid, and beautiful picture – of the meals his mother would cook, the clothes she would make and wear for herself and for the women in the community (no doubt inspiring her son in the process), and of the different people he grew up around. It’s full of tender moments and tough ones, too – the recounts of domestic violence and abuse, and the way women and girls were denied education or even the freedom to go to the shops without a male chaperone, are particularly harrowing to read. But ultimately, it’s compassionate towards his family and community, who faced unimaginable challenges – not only as migrants but as people living under the dark, devastating shadow of Margaret Thatcher’s government.

In its own review, Dazed said, “What Elena Ferrante does for Italy, Yousefzada’s The Go-Between does for Immigrant Britain,” and it’s true: this book will change the way you look at Britain forever. The way it was – and continues to be – seen and experienced by migrants; the way it was seen and experienced by people still living in its former colonies. (Spoiler alert: it’s not as flattering as Britain’s own accounts.) The Go-Between will open you up to a world that you never knew existed, but did so on the next street.

Here, Yousefzada delves into the book, speaking on Britain, his community and what it was like translating these stories to paper.

Ted Stansfield: The title of the book is The Go-Between and that’s what you were – a go-between. Can you tell me a bit about how you understand your identity and experience as a go-between and why you chose this for the title?

Osman Yousefzada: A go-between is someone who has a pass to enter spaces, sometimes for a short period of time, sometimes for longer. However each space has its own sets of codes that you need to learn; its own rituals; its own rules of what is right and what is wrong, who is accepted and who isn’t. It’s these dimensions that I have tried to navigate, predominantly through the eyes of a child.

TS: Has the book stopped you being a go-between or helped you bridge the gap between these worlds?

OY: It has hopefully bridged gaps, rather than widening them. Hopefully it will help people understand the worlds that we do not see, with empathy. The racialised labour – the way migrants are discarded and are not embraced; the way they live in close proximity but are not included in our conversations or narratives. Hopefully this book opens up borders, rather than closes them down.

“I think the story of the women was particularly important ... A world behind a curtain in the centre of a red-light district”

TS: Your book – in the most rich, and beautiful way possible – reveals to us this hidden world, which many people, even or especially those who were living in the UK at this time, would not have been privy to. What parts of this hidden world were you particularly keen to reveal?

OY: I think the story of the women was particularly important. How they created parallel economies – they saved together, created saving societies, looked out for one another, swapped information. A world behind a curtain in the centre of a red-light district. The extremes are so interesting, the role of the sex worker outside, and the woman in purdah inside, and then the white lodger Mary, and the unspeakable bonds, where language wasn’t important between them. It was these relationships as pioneers, and women who were diasporic but in another frontier in the UK, rather the Frontier in Pakistan, and how they navigated this space.

TS: The book really changed the way I look at Britain and British multiculturalism, as well as Britain’s role in the world – particularly the Frontier. It was especially interesting in the way that you spoke of your collective perception of Britain. It’s often the other way around – British or western cultures observing ‘the other’ or ‘the Orient’. But you turn it back around on Britain. Can you tell us a bit about the perception of and relationship to the Britain that you grew up with?

OY: Our parents always thought they were going to be chucked out – it reminds me now of the citizen bill, which I feel insecure about. I was born here, however I still feel unstable about where I really belong. The search for identity is continuous for me, across the fashion space, the art space, the racial space, the class space, the sexual space … My first girlfriend called me a ‘paki’ and ran into her parents’ pub. Which is funny, but walking side by side with a white girl as a child in a predominately Asian school, was a novelty. Naturally we looked inwards for safety – our parents didn’t have the codes or skills to integrate, nor were they allowed to. But sometimes that ‘inwards identity’ can’t contain what you are searching for, especially for someone like me. I think personally, I always felt like an outsider, an observer.

TS: How has your community changed since your childhood and how is it the same?

OY: Yes, very much so, it has changed. There is a strong professional class of Muslims – girls going to university and boys in professional jobs, who are straddling a Muslim identity as well as British one, as well as a Pakistani one. It is very different from when I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, yet the community spirit is very strong. They band together for births, deaths and marriages, and the rituals of religion hold them together. It’s the other side, the afterlife, that is also a key focus: how we prepare for the here-after.

TS: Another thing that was super interesting was the part about Thatcherism and deindustrialisation, and how that impacted your community, and how it changed your community’s relationship with religion. Can you tell me a bit about this?

OY: When men came here in the 60s they were these dapper gentlemen, all looking like movie stars in black and white photographs, clocking in everyday at factories, doing double shifts. But when Thatcher closed down all the factories, these men who worked in foundries and did the jobs that no one wanted to do, couldn’t retrain. They were illiterate and couldn’t just work in a call centre. They were discarded. For a period of time they had tried to assimilate, wearing flat caps and two-piece suits, but in the 80s when their livelihood was gone, they were on the dole, with time on their hands, they were worried about their future and what their children will be in this no-man’s land. They needed to keep their dignity and they had time to understand the scriptures, time to correct their prayers, time to devote to God, and time to make sure their children were guided on the right path.

“But when Thatcher closed down all the factories, these men who worked in foundries ... couldn’t retrain. They were illiterate and couldn’t just work in a call centre. They were discarded”

TS: You paint such a beautiful portrait of your mother who recently passed – what was it like writing about her and publishing this book in which she features so prolifically? How did the process of writing the book change your relationship with her?

OY: My mum died on New Year’s Day, so I don’t think New Year’s will be the same for me again. She had such a strong impact on my life. Her ways were gracious, and wise for someone who couldn’t read or write. She created a tight community around her, called upon everyone, made everyone her own. I wrote quite a few of her sayings, one I remember all the time: “two words can become an insult and two words can become a gift, so use your words wisely.”

TS: You’re so generous with this book, you give the reader so much. How did it feel being so open about your life, experiences and people who in many ways shaped you?

OY: I don’t know, I can’t really recall what I’ve written, it’s been a ritual cleansing. And it drew a line, a foundation stone; it’s a creative act, and now it’s out in the world. I’m getting hate from some corners, but for me, it was an act of love, and recording of stories before they are lost. These are the stories of the illiterates who can’t tell their own stories.

TS: The book has already received some glowing reviews – including one from Stephen Fry who called it “one of the great childhood memoirs of our time”. What has the wider reception been like and how have you experienced that?

OY: It’s been quite positive, fingers crossed … I do see it as an artwork. The Independent said yesterday that it was evocative prose that skilfully charts both outer landscapes and inner emotional worlds, and captures the feeling of being an outsider, as well as the yearning to belong. If it helps misfits and dreamers like myself to vocalise what they are feeling, and to find a creative path, then that would be very beautiful. Especially as I have the eternal imposter syndrome.

TS: Do you feel like you went into this book with a goal? Are you trying to achieve something through this book – if so, what? What’s your hope for it – is it going to be a film or a TV series?

OY: No, it was documenting, but everyone has said it is very filmic. Who knows? Inshallah!

TS: How does this book fit within your wider practice as a multidisciplinary creative? You’re quite a modest person but your projects take up a lot of space. And you have a lot to say. I’m interested, what’s next for you?

OY: I’m working on a moving film for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney and the Ikon in Birmingham, which will be shown simultaneously. Its about ritualised space and transformation – across two spaces, one is a Sufi space and one is a transgender space. Also, from July to September, I have a series of contemporary art installations at the V&A, which is part of the PK-UK season commissioned by the British Council to celebrate 75 years of Pakistani Independence. Plus, the annual Migrant Festival, which I initiated and curated in 2018, and is another platform for those who want to use their voice on the one of most securitised conversations of our times.

The Go-Between: A Portrait of Growing Up Between Different Worlds by Osman Yousefzada is out now, published by Canongate Books Ltd.