Charlotte Adigéry and Bolis Pupul have a strong aversion to cliches. One day when they were on tour, they heard a song on the radio that opened with the words “I was walking down the street … ” Wondering why anyone would open with such an unoriginal line, they decided to collect all their favourite lyrical cliches on a song of their own. Ceci n’est pas un cliché is a rundown of pop’s most overused phrases: “my heart is beating like a drum” and “let’s dance the night away”, for example.

The song appears on Adigéry and Pupul’s debut album Topical Dancer, which captures the Ghent duo’s general approach to music – taking something that’s amusing or interesting to them, and writing about it in a way that’s not been done before. This applies to both their lyrics and to the music itself, a club-ready electronic pop sound that’s refreshingly free of familiar genre usual trappings and formulas. As Topical Dancer’s title implies, Adigéry and Pupul talk about today’s hot-button issues – cultural appropriation, sexism, racism, political correctness – but despite the heavy subject matter, their approach is lighter than air. Laughter is the main component: Huile Smisse is named for the phonetic French pronunciation of actor Will Smith, while HAHA is literally just a recording of Adigéry’s laughter in the studio set to a chugging rhythm. Their lyrics are sharp, satirical, and specific, a rejoinder to pop music that tries so hard to be for everyone that it ends up saying nothing at all.

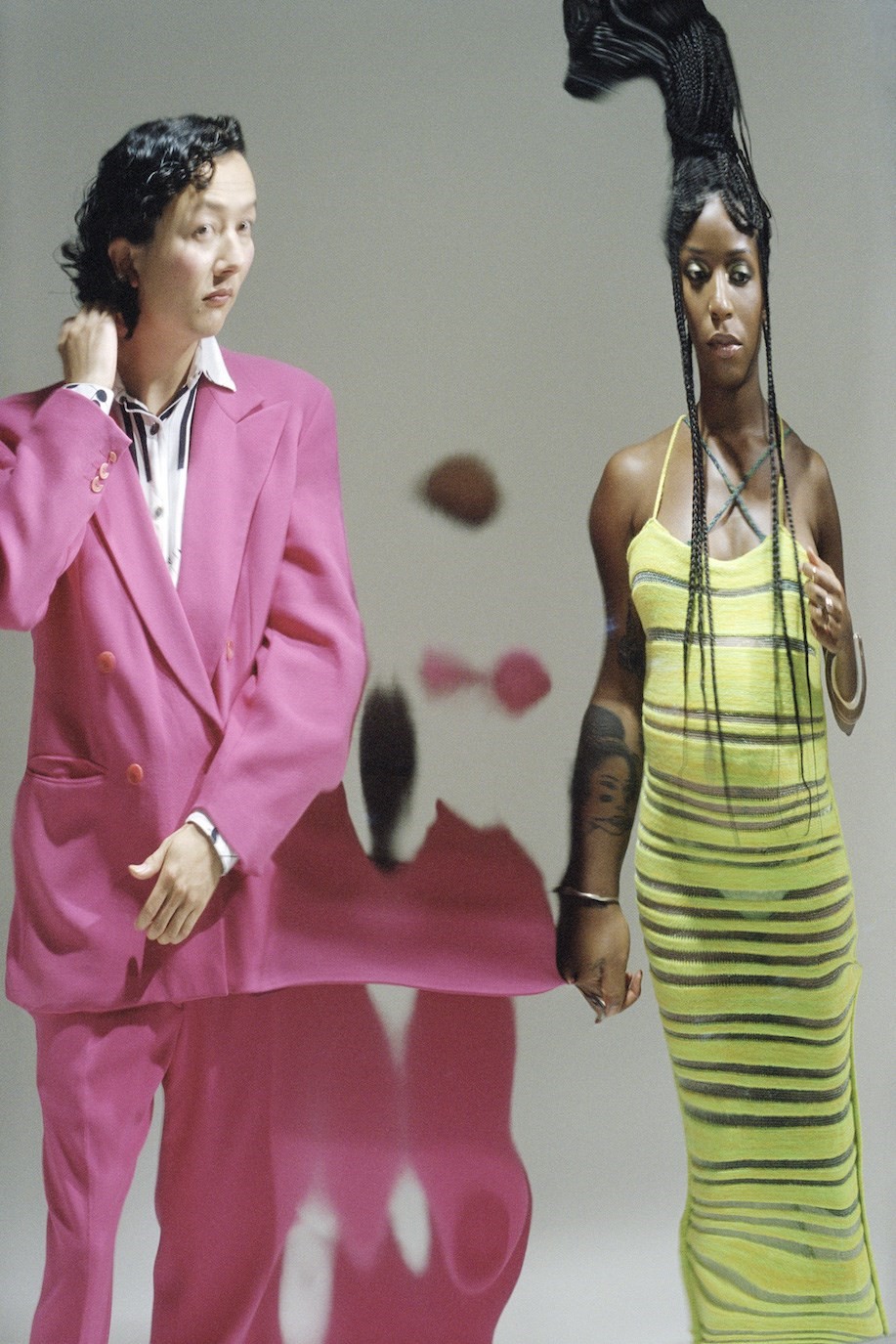

Adigéry and Pupul first met at Studio Deewee, the compound run by Stephen and David Dewaele (of Belgian electronic/rock legends Soulwax and 2manydjs) as both a music studio and headquarters for their Deewee record label. Pupul was working as a studio hand at the same time the Dewaele brothers invited Adigéry to perform on the soundtrack they were recording for the 2016 film Belgica. They sensed that Adigéry and Pupul could make good music together, with complementary personality types and similar-yet-different backgrounds as the children of immigrants in a predominantly white Belgian city (Adigéry has parents hailing from Martinique and Guadeloupe, and sings in English, Dutch, French, and Creole, while Pupul is of Chinese descent). The Dewaeles handed over the keys to the studio while they were away on tour, and when Adigéry sat down with Pupul, the first thing she played him was a song by The Slits. Pupul understood this had more to do with the punk band’s “intensity and approach” than it did their genre or technique, an attitude they carried over into the music they were making together. By the end of the week, they’d written enough songs for their first release, and a month later they released their debut EP.

Since then they’ve put out a second EP, contributed an original track to Deewee’s Foundations compilation, and released a guided meditation tape. While those previous releases were credited to Charlotte Adigéry as a solo artist (Pupul, born Boris Zeebroek, has separately released solo records of his own via Deewee), they decided that Topical Dancer should bear both their names. While Pupul is mostly the producer and Adigéry is the vocalist, they both play an equal part in the process, with Adigéry going so far as to wear a T-shirt with Pupul’s face on it in early press photos. We spoke over Zoom while Adigéry (who was visibly pregnant during the photoshoot for Topical Dancer’s album cover) held her young baby in a sling.

Selim Bulut: Bolis, I read that Charlotte played you The Slits the first time you met. Where else do your respective music tastes converge?

Bolis Pupul: Destiny’s Child, TLC, 90s R&B. But also the classics: Prince, Talking Heads, Roxy Music. Charlotte got me into Kassav, a band from Guadalupe who play zouk. It’s super groovy music that makes you happy to listen to.

Charlotte Adigéry: There’s not a certain genre we don’t like, we both have eclectic tastes. And there are elements of music we don’t like, and that’s where we also converge – if it doesn’t feel authentic, or if it’s cliche.

BP: That’s very important – to dislike things in common!

SB: The album’s called Topical Dancer, and it deals with these topical, timely issues in its lyrics. Is that something you set out to approach deliberately?

CA: The album is a result of conversations in the studio, just as friends talking about things we are going through as ourselves or as a generation, and deciding to make a song out of it. We did that for two EPs, then said, ‘Let’s continue with that, because we’re not finished talking about it yet.’ Doing these interviews, we’ve realised now what that symbolises. Lots of people have said that it’s a very political album, but me and Boris often react: ‘Really? Is it?’ We don’t feel that engaged. It’s nice seeing reactions on Instagram where people really understand the lyrics, but it’s not [like we set out to say], ‘We’re gonna change the world! We’re gonna change electronic music!’

BP: The listener can be the third person in the room when we talk about what we’ve been through, or what we’re frustrated about. It’s not done with the intention of being moralistic or finger-pointing. It’s more like putting out our thoughts.

SB: I find a lot of musicians tend to write very vague, wishy-washy lyrics, but yours are very specific and very distinctive. When did you get seriously into writing lyrics?

CA: That’s my intention, to really address someone directly. While you were asking that, I had this flashback of going to the library and getting out a book called How to Write Songs. Like, ‘Writing a song is not like writing a poem. OK, I’ll try to internalise that.’ When I was 18, I had a band where the drummer wrote the lyrics, because I could not get past two sentences. It was so frustrating. When I went to music school – it’s not sexy to talk about school when you’re a musician, but that’s my reality – I had to write a lot of music and realised I could just write how I felt. I needed to be honest and write about my own life. I was very aware that I wanted to say something, but I was allergic to these clichés. The first and second EP were really transformative and really created my style of writing. Thanks to Boris, I felt free (to write anything). The first time I met Boris, I was going through these field recordings. There had been a guy who was hitting on me, and I recorded him doing it because the way he did it was so stereotypical. So I said to Boris, ‘Can we do something with this?’ He said ‘Yeah, of course.’ And I started to imagine this story. It felt like opening this door of possibility. ‘Wow, I don’t have to talk about my feelings – I can describe other things!’ Stephan and David’s manager told me, ‘I love the way you write, because you can tell you’re not a native speaker, but it makes it very direct and very universal.’

SB: It’s funny you say ‘universal’ because a lot of artists say they keep their lyrics deliberately mysterious so that the listener can bring their own meaning to it. But I always think it’s the other way around, where the more specific the lyrics are, the more vividly I can picture it – and that’s what ends up giving it this relatable quality.

CA: I agree. I always feel stupid when lyrics are vague. I don’t understand what you’re saying! I just zone out.

SB: The album avoids a lot of musical cliches too. It’s not really trying to sound too much like what you’d expect from a specific genre.

BP: Me and Charlotte get easily bored when we write a song and we feel it’s going too much in one direction. It’s too techno, or too four-to-the-floor. We always have the urge to look for something that comes from another world. Sometimes you have to search for the right ingredients.

CA: When we look at a song and there’s a problem with it, we always refer to the elements as ingredients. ‘This song needs more pepper, more spice, more zest of lemon to balance it out.’ Otherwise you have this super sweet dish that everyone knows.

SB: Your music can be very funny but I do find a lot of it quite difficult to listen to. In Blenda you deliver a line like ‘go back to your country where you belong’ in this casual and almost humorous way. And I find that by wrapping it in humour, it actually becomes even more difficult to listen to, because it’s harder to ignore the force of those words.

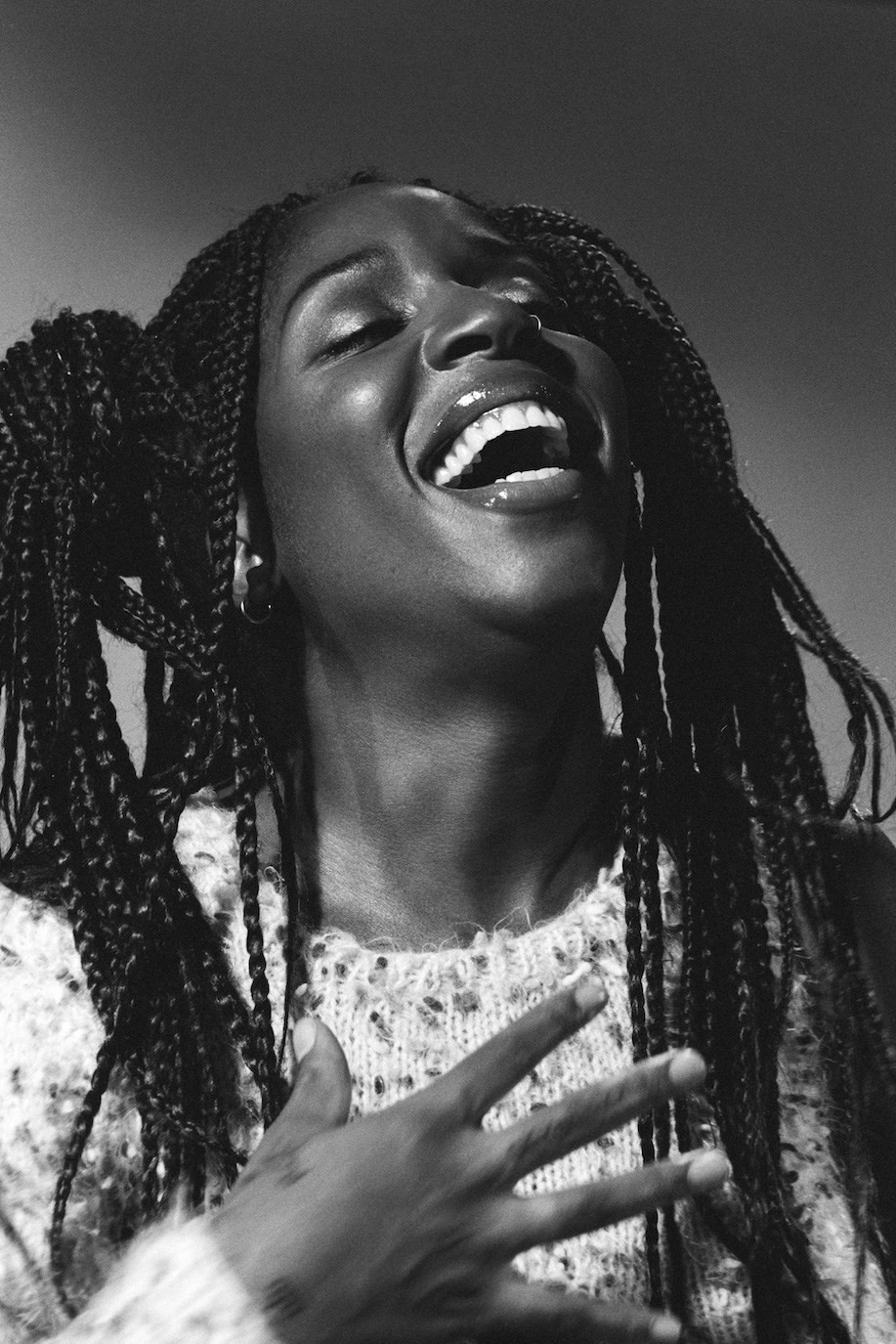

CA: People can be very sensitive about certain topics, so saying it while laughing maybe gets accepted more easily. Humour and laughing and not taking ourselves too seriously is something that bonds us. All of these things are serious and horrible. We’ve suffered a lot as foreigners in a western country. But we don’t want to become bitter. Humour is a great way to make a point without being moralising. You can be moralising, but everything is a balance. There was a Belgian journalist – a white woman – who said, ‘I love Blenda, but I feel so awkward singing along. It doesn’t feel right.’ And I thought, ‘That’s cool, actually. I’m happy.’ That’s a good way of confronting people with topics like that. You’re in the kitchen and you’re dancing to it, and you’re like, ‘Oh! I can’t sing along to this!’

SB: Have you performed it live yet? What did the crowd do?

CA: People of colour, Asian people, and Black people – they were really going for it. The others didn’t. Maybe we should check in about this next time! But I wouldn’t be offended if they sang it …

BP: Me neither – unless they really meant it. Maybe we should challenge the crowd? (Rock star stage banter voice) ‘Everybody, sing it!’

CA: ‘Now the white people, go ..! Now the Black people, go ..! Now the two Asians in the crowd, go ..!’

SB: What song are you most excited for people to hear?

CA: I would say Esperanto.

BP: Ah!

CA: You too?

BP: I knew you were going to say that. Me too. It was one of the first songs we wrote, and one that’s most about the sign of the times.

CA: The ‘don’t say this say this, say that’ part, I’m curious to see if people will get it. Some topics are different here in Belgium than they are in the UK or the US. ‘Don’t say black Americano, say African-American’ – it’s a stupid joke, but how will people respond to that joke in the US?

SB: And what’s your personal favourite moment on the album?

BP: Making Sense Stop was one of the last songs we wrote. We wrote so many songs, and listening to them, we felt it was very opinionated – so can we do something lighter and less opinionated? Maybe we don’t want to say anything? David Byrne said ‘stop making sense’, so OK, let’s stop. Let’s do the cut-up technique and sing it and look at the phrases and play with repetition. It portrays our playfulness to music. Sometimes you have to stop making sense. Nonsense is important.

Charlotte Adigéry and Bolis Pupul’s debut album Topical Dancer is out 4 March 2022.