Sheila Heti cannot picture God. As someone who grew up “almost aggressively” atheist, God is not as tangible as a tree, or her brother, or her grinning rottweiler Feldman, who hulks into view on our Zoom call to settle himself in front of a stacked bookcase at her feet. Instead she thinks of ‘God’ as a cavernous, open word. The concept of a divine power is elastic and malleable in the acclaimed Canadian writer’s hands, with which she takes to rewriting the creation of the universe in her latest novel, Pure Colour.

An impending apocalypse is made meditative and sweet with Heti’s prose – the narrator Mira, studying to be an art critic, along with the rest of humanity is living in the “first draft of existence” by God. Human beings’ complaints and tribulations are logged as feedback for the next iteration of the universe. Building on the creation myth concept, God is “hoping to get it more right this time,” Heti writes, and “God appears, splits, and manifests as three critics in the sky”.

In this world, humans are categorised as three of these kinds of critics, as animals. There are birds (captivated by beauty and aesthetics), fish (who feel fiercely responsible for the collective and justice), and bears (who do not care for the abstract or ethics, but what is immediate). Think of your favourite writers and artists, divisive critics, and try to categorise them by Heti’s animal key.

Mira – a bird – falls for Annie, a cool and distant fish. But the encompassing relationship is with her father, who is a passionate, loving, stifling bear. He dies early in the novel, and his death dovetails the story into the abstract, in which the universe “ejaculates” his spirit into Mira, and from which their souls are drawn into a leaf, where they live and discuss life for some time. The leaf is a stunning metaphor for the painful, profound life cycle of grief. (Heti, like her protagonist, is “obviously” a bird, she tells me with a laugh.)

Heti did not set out to write about grief. She had originally begun writing a novel about art criticism, but the death of her own father in 2018 saw Pure Colour expand across her navigation of loss. After longhand writing about her personal experience, she realised that the questions she was parsing belonged in the novel. The process was unlike any of her other nine books – she spoke into a tape recorder, transcribed with a text to speech programme, and listened to it on runs from which she edited drafts.

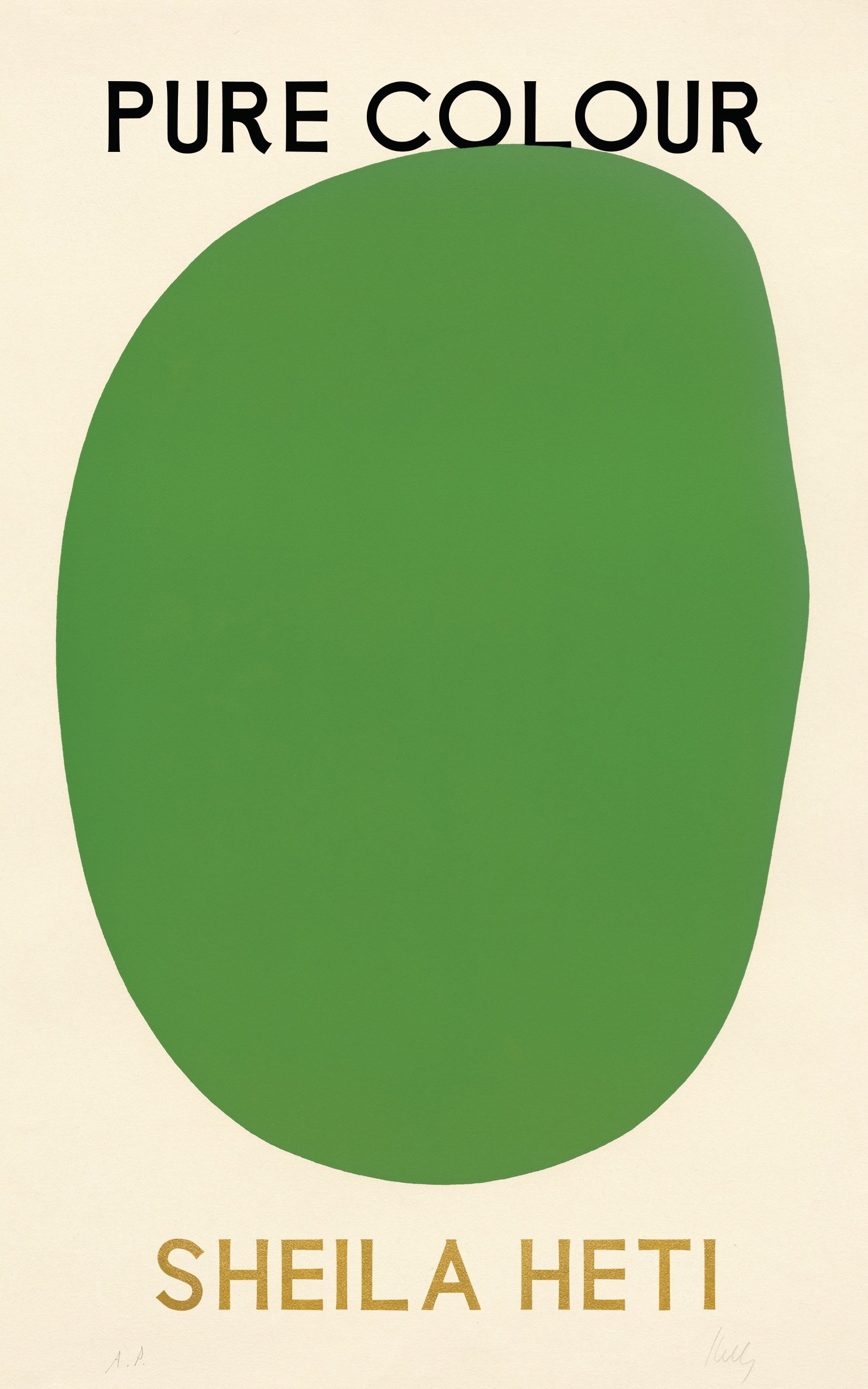

This fourth novel arrives four years after Motherhood. With an originality and perceptiveness that built upon 2010’s How Should A Person Be?, Pure Colour cleaves away any perceived notion of what she’ll write next – it is philosophically intense, poetic, deftly capturing an impressionistic emotional reality we all experience differently. Here, she discusses Pure Colour as a present-day fable, looking at the end of the world in a different way, and whether family, love, or art can make up for life’s other inadequacies.

Anna Cafolla: Pure Colour is unlike anything you’ve written before. Was the writing process different?

Sheila Heti: I started it in early 2018 and wrote the whole thing in Toronto. I was writing for about a year before my father died. I feel like the book had three main phases of work – before, in the thick of his passing, and then a year or two later.

Usually when I write it’s all over the place – I’ll find the order of the things after. But this book kept unfolding to me. I would write and think, well, the book is done, that's all. And then there'd be this whole new phase of work. That was a surprise. I wrote this book more chronologically than I've ever written before. I felt very alone when I was writing. Grief separates you from other people. You step outside of society and culture for as long as you're grieving. It's such a private, incommunicable internal experience. My other books focused on conversation with other people and curiosity about what other minds were experiencing, who had the answers. I thought I wanted to write a book about art criticism, and then that exploded. I had the idea that this book would be historical, or a little more academic than other things that I'd written, and it just wasn't that. I always like to let the book lead me. Writing is in collaboration with whatever time you're in at that moment. This didn’t have the form until I finished and stepped back.

AC: How did the concepts of God and grief meet critic and artist?

SH: As an artist, I get so much criticism – I read my criticism and take it in. To transmute that feeling of powerlessness and pain, I began to think of God as an artist – what does it mean for the creator of the universe to hear our criticisms of his creation? I'm Jewish, but I’m an atheist, and yet the concept of God is still so meaningful to me – to transform something beyond yourself.

I want to find what’s valiant and strong in difficult moments rather than focus on suffering. The initial idea came from writing How Should A Person Be?, in 2006. I had the sentence ‘what if God is three art critics in the sky’ circling my head for years. I don’t know where it came from, but I had to understand – why three? How are they different? And, I am in the unfortunate situation of being a bird! Maybe the one that is hardest to justify in this current world … I mean, a preoccupation with beauty and art in a world that is in political turmoil – but when is it ever not? It can seem like a frivolous thing to be a bird. I hope in this cosmology that it’s clear God wants all these creatures. There is a purpose for the fish, bears, birds.

AC: How did your concept of grief evolve?

SH: I didn't know what grief felt like until my dad died. I was surprised by how psychedelic it was. The whole architecture of what life is, anchored by a parent, falls away. The universe felt like a completely different place suddenly, and, absurdly, I felt like I was on drugs.

Since I was a little girl, I dreaded death. But I found, with that suffering, the world was being made new to me. I felt like I had new eyes. I’m always writing, even if not writing a book. I wrote about his death first to document it for myself. I hadn’t read before that grief could be as ecstatic as it is sad. It seemed to me like that was something to put into the world, another possibility. Surely that could be an aspect for others. Something … exciting? You're so stunned by this new course. I want to put down in books what I haven't really seen from other humans. What books are good for is expanding our ideas of what life – and death – can be.

“I felt very alone when I was writing. Grief separates you from other people“

AC: Did you see the thread between Motherhood and Pure Colour? I was thinking about time as a sentient character in Motherhood, then how mothering itself is like making something in your image, someone who grows up to critique and challenge you.

SH: With Motherhood, I was really writing to an audience. I wanted it to occupy a culture. This time, it was more for myself – or if not that, to serve a more cosmic purpose. There’s no emotional or intellectual map for humanity as I think there is assigned to motherhood. There was a very deep reason to write Motherhood. I wrote that book so my mother would stop crying. It's a simple, sweet, basic reason. I want to ask this of art too – people sacrificed so much so that they can have a life making art, and why?

It’s interesting how deep an instinct it is in humans to make art across cultures and time. There has always been this need to make models of our experience, to make them beautiful for other people. It’s not like eating or having sex to me – I think it’s like making a family. You make a human family by creating symbols and stories.

AC: There’s so much access to everybody’s critiques now. Access to the internet, to art more widely, has been democratised. Was this book a way to unpack this levelling?

SH: We’ve been given this opportunity to all be public critics. I can find that upsetting. I wanted to find the beauty in this swelling of criticism – not just in our culture, but in a cosmology, a creation story. Criticism has been beneficial for social and justice movements, but for art it’s a more complicated question. Bigger than the internet!

What’s really got to me … how come we can experience the majesty of the world but constantly be preoccupied with little complaints? We have this rare opportunity to experience a glorious planet, but it’s clouded by pettiness. How can this be made worthwhile and productive? Maybe it’s that God wants us to be his critics, and not enjoy this life so it can bolster the next. Maybe in the next draft, we won’t need families or art to survive as we do now. Families and art make up for life’s other inadequacies.

AC: Does climate anxiety play a part?

SH: I was on tour for Motherhood while I wrote this book, and I was reading David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth. I was on aeroplanes, in other countries, going from store to store … just thinking about how we produce and consume so much stuff! It was so powerful. That inspired a lot of my thinking. But I read a lot over the process, some not very directional reading. I reread Crime and Punishment. When I first read it, I was younger than [Rodion] Raskolnikov. And now, I’m like Raskolnikov's mother’s age. It’s funny to revisit stories and see how moments have differing effects.

“We’re moving away from the cultural expectation of needing a degree to be a writer. If you write, you're a writer“

AC: I was watching this interview you did with Miranda July in 2015, where you quote her words – ‘Things usually make sense in time, even bad decisions have their own correctness’. I was thinking about that in terms of God’s drafts. Does a ‘perfect’ draft of art, or life, exist? Should it?

SH: I really love unfinished feeling works of art. Like a Monet sketch at the Met – half is pencil and half is paint. It’s the most transfixing. To see the process and to have it be unperfected and unfinished … I love that living, yet to be lived feel. So the question … we all want to get rid of all the suffering on Earth. We want utopia. I wanted to make the case in the book that there's something amazing to find in turmoil. If you can’t change the world fundamentally, how can you live in it in a way that makes it bearable, even beautiful? That was propulsive. If my father has to die, what can be beautiful about it? If we are responsible for our oblivion and there’s no turning back – what meaning can there be? That’s a question not for public policy, but for art.

AC: One of the most profound moments in a person’s life, I think, is when you realise your parents aren't invincible. It’s not nice, but it sets you on a path towards recognising your own independent thought and path, maybe even the power of infallibility.

SH: And yet it has to happen right? Imagine a 30-year-old who thinks their parent is a superhero!

AC: What do you make of being called a philosopher?

SH: I think it's a nice word to use for people who love thinking. I think that the more democratic that word can be, the more people that can encompass, the better. I feel the same way about the word writer. We’re moving away from the cultural expectation of needing a degree to be a writer. If you write, you're a writer. If you love wisdom, you should be a philosopher.

AC: I read each section like poetry, and let it lift me in different directions. How conscious were you of giving readers the space to ask questions of your questions, to philosophise themselves?

SH: I always have this question of how complete I want a novel to be. How many threads do I tie together? How tight with answers do I make it? I chose looseness. Otherwise, I would give the wrong answers! It forces me not to make up anything for the sake of filling in the blanks. I couldn’t answer every question that the book raises, and I shouldn't.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti is out now.