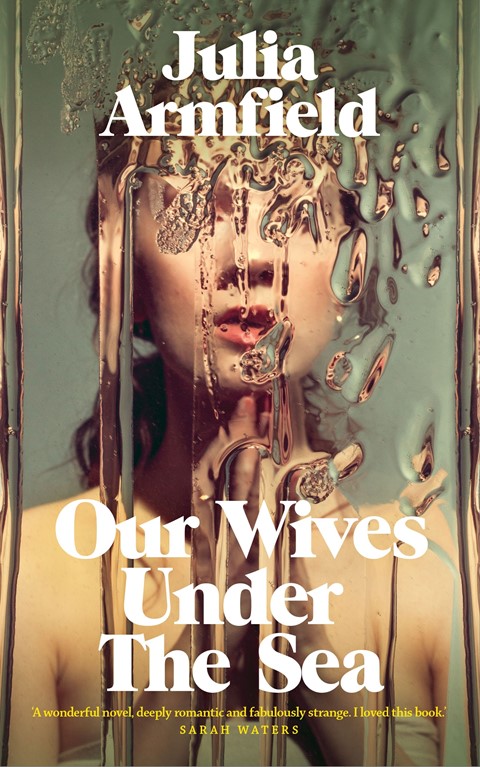

The author talks through her debut novel, Our Wives Under The Sea – a queer gothic fairytale set in the darkest depths of the ocean

“A contemporary gothic fairy tale, sublime in its creepiness”, reads Florence Welch’s review of Julia Armfield’s debut novel, Our Wives Under the Sea. But, as readers will quickly discover, Armfield’s portrayal of marital life gone askew after a disastrous deep-sea mission is as fluid in its genre as the ocean itself.

The story takes place after Leah, a marine biologist, returns home from a five-month-long mission. The expedition, which was only supposed to last three weeks, leaves Miri displaced with her grief as the wife she had presumed was dead has finally come home. Memories of what they once shared are now just that, as Leah seems consumed by a strange affliction, an obsession with bathing, and is all-consumed by whatever happened below the waters.

While Armfield’s novel certainly uses the ocean’s unknown as the perfect setting for psychological horror, Our Wives Under the Sea may be thought of more aptly as the portrait of a marriage breaking down. Miri, convinced that Leah has ‘come back wrong’, slowly comes to terms with a new kind of loss, in which the woman she once loved is now nothing but an empty vessel and the promise of a normal life is slowly slipping away. A refreshing take on queer fiction and horror, Armfield sat down with AnOther to discuss the book, her relationship with Catholicism, and her obsession with the sea.

Katie Tobin: One of the key themes throughout the novel is faith, or the lack of it. From Miri’s Catholicism, Matteo and Leah’s atheism, to Jelka’s constant praying. What is your relationship to faith, and how did this shape the novel?

Julia Armfield: I think I find myself writing about Catholicism specifically, it came up in my short story [Salt Slow] collection too. I went to a Catholic school, and that just keeps happening to you in your brain for the rest of your life. I also went to church for a very long time as a child, and it sort of filtered away, the way that it filters away, but it leaves you with preoccupations. I’m preoccupied with guilt, I’m preoccupied with death, I’m preoccupied with the way that one can consider one’s self more incidental if one has a sense of faith, or the way that one can consider themselves much more central to the universe, and the way those things impact on one another.

It’s not that I think that everyone who is an atheist thinks that they’re the centre of the universe, but I think there’s a way in the novel that people’s reactions to horror specifically are augmented by faith or lack thereof. It doesn’t mean that they think in one particular way, but it’s always impacted by faith to some degree.

KT: Although a queer novel, it refreshingly steps away from the classical coming-of-age format or a narrative where the central characters are coming to terms with their sexuality. Instead, the novel is more concerned with how queerness is perceived by others. What are your thoughts on portraying queerness in this way?

JA: I was always going to write a queer novel as I am a queer woman; I was writing what I knew. I’m interested in the circles of expected existence that people move through in traditional heterosexuality that we don’t move through, necessarily, as queer people. That obviously doesn’t mean you can’t get married, and you can have children, but everything is thrown off its normal whack as you don’t have these traditional spheres to move through in quite the same way. I’ve always found it interesting to write about the things that queer people can pick and choose for themselves and the things that they aren’t allowed and the things that they are allowed.

Even in the sense that Miri and Leah are both cis women who are married, and therefore are seen as semi-acceptable in the way that they’re perceived by the world, there is an enormous amount of assumption being made a lot of the time about queerness. I’ve always been interested in the ways that one can be as ‘acceptable’ as possible and yet the world will still try to need you in a different way.

KT: In fairytales, typically the sea is presented as a mythical space, associated with femininity (like sirens and mermaids etc). While there are lots of anatomical references to sea life, I’m curious as to what drew you to the sea as a setting for psychological horror?

JA: I’ve always been interested in the water. I have about ten preoccupations I keep coming back to over and over again. The end of my short story collection is very much inspired by the ocean. But I’ve always been fascinated by the fact that we think of the place we live as the real world, but so much more that exists under the water.

Returning to the idea of faith, I’m so interested in the sheer incidental-ness of us as people, and it’s not unlike when people go to space or write space novels. I’m interested in the smallness of people and the relative smallness of people towards the world, and towards what’s under the water and what’s under the sea. In writing about the ocean, it’s also just a very workable metaphor for the forces that one cannot resist; the crushingness of grief and distance and the way that there’s so much we cannot control. It’s not an intentional metaphor but it’s very easy to work with.

“I’m interested in boring things ... I like the way that dailyness communicates with horror, and that people who experience horror tend to cling to routine and cling to a sense of normality” – Julia Armfield

KT: How did your prose style influence how you structured the dialogue between Miri and Leah, and the very nature of their relationship?

JA: I’m interested in boring things and dailyness. I always have been. I like the way that dailyness communicates with horror, and that people who experience horror tend to cling to routine and cling to a sense of normality. I don’t think people really react in outlandish HP Lovecraft ways, they kind of just get on with it. That was always my base; I didn’t want to be writing two people screaming at each other.

I wanted to write about two people going around their boring daily lives in a horror novel. The way that the conversation happened to me was knowing the characters well enough in my head. Leah was very routine-based, intellectual, and a process-based person, and therefore that would be the core of her voice. Whereas Miri’s voice was always going to be slightly more neurotic and emotionally driven. I had to figure out what would be the most absolute boring normality for each of them, and let it grow out of that.

KT: Do you have anything that you hope readers will grasp from the novel?

JA: I hope it makes them want to read more novels and poetry and short stories and fiction in general by queer writers, as I think I’ve been incredibly fortunate with the place this has fallen and the audience this will have. I think people are leery of genre and leery of horror and sci-fi and people shouldn’t be. Some of the most interesting and intelligent writers are writing in those genres.

KT: And finally, on that note, do you have any writers that you’d classify as inspiration?

JA: I recently read Devil House by John Darnielle, which is amazing. I read a lot of Stephen King, and I’ve just read Parallel Hells by Leon Craig, which operates in a very similar genre which was great. And Becky Chambers, really brilliant, often queer sci-fi.

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield is out now and published by Picador