In a new book of essays about women and music, the American author writes about romance, mixtapes, and pretending to like her first boyfriend’s awful taste in music

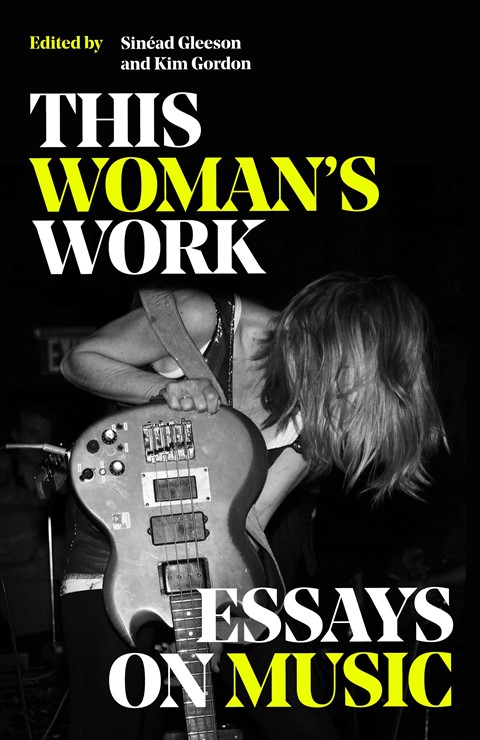

The following excerpt is taken from This Woman’s Work, a new book of essays edited by Sinead Gleeson and Kim Gordon.

The first boy I ever kissed was also the first boy I ever slept with; he was also the first boy who ever gave me a mixtape, and the first boy I ever fell in love with. You could say I moved quickly, or else you could say I was a late bloomer, depending how you looked at it. All this happened during my senior year of high school.

I’ll call him Mark. He had bright blue eyes like chipped shards of sea glass, fine blond hair like a downy fur across his scalp, and a pair of tattoos he kept hidden from his parents. He’d gotten the second one right between his shoulder blades a few days before his high-school graduation, and he spent the whole day wincing as well-wishers clapped him on the back. His arms were covered in cuts he told his mom were cat scratches. I knew the truth. I cut myself too.

I was so crazy about Mark that I’d even gone with him to a 311 concert. And even I – generally so malleable to a man’s desires that I could barely discern my own – could tell how shitty their music was. I mean, you didn’t have to call information to find their blandly sugar-coated, hacky-sack pitter-patter stoner riffs both grafted and grating. Amber is the colour of your energy? Not mine!

But Mark’s relationship to positivity, as conversational default and life philosophy, was born from root systems of pain that ran deep into his childhood. For this reason, I respected his general desire to ‘keep it light’, musically and otherwise. This righteous forbearance took me all the way to Santa Barbara for a 311 concert where the moral of most of their music seemed to be: This song is impossible to enjoy unless you’re stoned. Only trouble was, I generally got anxious and twitchy when I was stoned, which didn’t stop me from doing it a fair amount anyway. (See also: malleable to the desires of others). I was the stoned girl circling the swimming pool, telling the other kids it really wasn’t safe to be in there if they’d been drinking – which was pretty much the opposite, I realised, of what being stoned was supposed to feel like.

Anyway, my one true 311-loving love made me a mixtape! This was right before the dawn of Napster and the ascendance of digital music, right before mixtapes started to feel like artefacts of the past. It was also right before Mark and I left for our respective colleges. Just a few days before my flight across the country, he told me he didn’t think we should stay together. Long-distance seemed untenable, and he was staying on the West Coast, while I was headed East; which I’d come to understand as the more sophisticated side of the country. At least, it was the coast where all the men in my family kept going. But now, this man was staying. When he said he thought we should break up, I got so angry I went home and smashed a stack of plastic cups against my bedroom wall, then used the shards to cut myself. I called him, basically hyperventilating over the phone, and he said he wanted to come and talk it out but his dad wouldn’t let him use the car. Double-digit feelings, double-digit problems.

When I drove to his house the next night, the last night before I got on an aeroplane to Boston, my heartache was a double-decker heartache: the sting of being rejected, and the shame at how fully this rejection overwhelmed me. It seemed to speak to a lack of inner resources.

“I was the stoned girl circling the swimming pool, telling the other kids it really wasn’t safe to be in there if they’d been drinking – which was pretty much the opposite, I realised, of what being stoned was supposed to feel like“ – Leslie Jamison

As soon as I arrived at his place, Mark told me that he’d made me a mix. It told a story, he said. We lay on his bed and listened: First came the jaunty stuff that represented our salad days, Blink 182’s iconic Josie, Yeah, my girlfriend takes me home when I’m too drunk to drive, and the inevitable 311: I know a drugstore cowgirl so afraid of getting bored … Then it veered hard into emo songs meant to express the ways we understood each other’s darker parts, the secret conversations between our scars, Eels singing: I am OK. I’m not OK. The tape culminated with the Bush song Alien, a power ballad lurking in the shadows of their better-known radio hit, Glycerine. And as Alien played in his bedroom, And she comes to take me away / She’s all that I needed, Mark told me that he’d changed his mind: he wanted to stay together. It was the most romantic moment of my life. I hadn’t had very many romantic moments, but this was romantic enough to make up for all the ones I hadn’t had before.

As the chorus bleated its plaintive, earnest gibberish – I’m an alien, you’re an alien / It’s a beautiful rain, a beautiful rain – Mark kept talking: he’d always felt like an alien. I was the only one who’d ever really understood him. Lying on his twin bed listening to Gavin Rossdale’s dark crooning, it didn’t even matter that the lyrics barely made sense (beautiful rain?). It didn’t matter if I didn’t like 311. It didn’t matter if I actually got a little annoyed when Mark got so drunk and stoned I had to take care of him. (I wanted to be the one who got so drunk and stoned I needed to be taken care of!) All that mattered was that I needed him to need me. It all feels impossibly innocent now – believing that saying I need you could be enough – but I still feel a tenderness for this girl, who needed, so badly, to hear this more than anything else.

This Woman’s Work is edited by Sinead Gleeson and Kim Gordon, published by White Rabbit, and is out now in hardback.