On the evening of Halloween 2015, 20-year-old Morgan Hehir was stabbed to death in a random, frenzied attack in a park in Nuneaton, Warwickshire following the most trivial of altercations. His killer, 21-year-old Declan Gray, had been released from prison just four months earlier, having already served time for manslaughter. Between his release and murdering Morgan, Gray was arrested three times. Yet he remained entirely unmonitored despite the repeated warning signs, coupled to his lengthy history of serious violence.

Later, it felt like Declan Gray was simply at liberty until he killed someone again. But the catalogue of failures that led to Morgan’s murder were not easily volunteered. Instead, the Hehir’s had to fight, and fight hard, for them to be made known, over gruelling months and years.

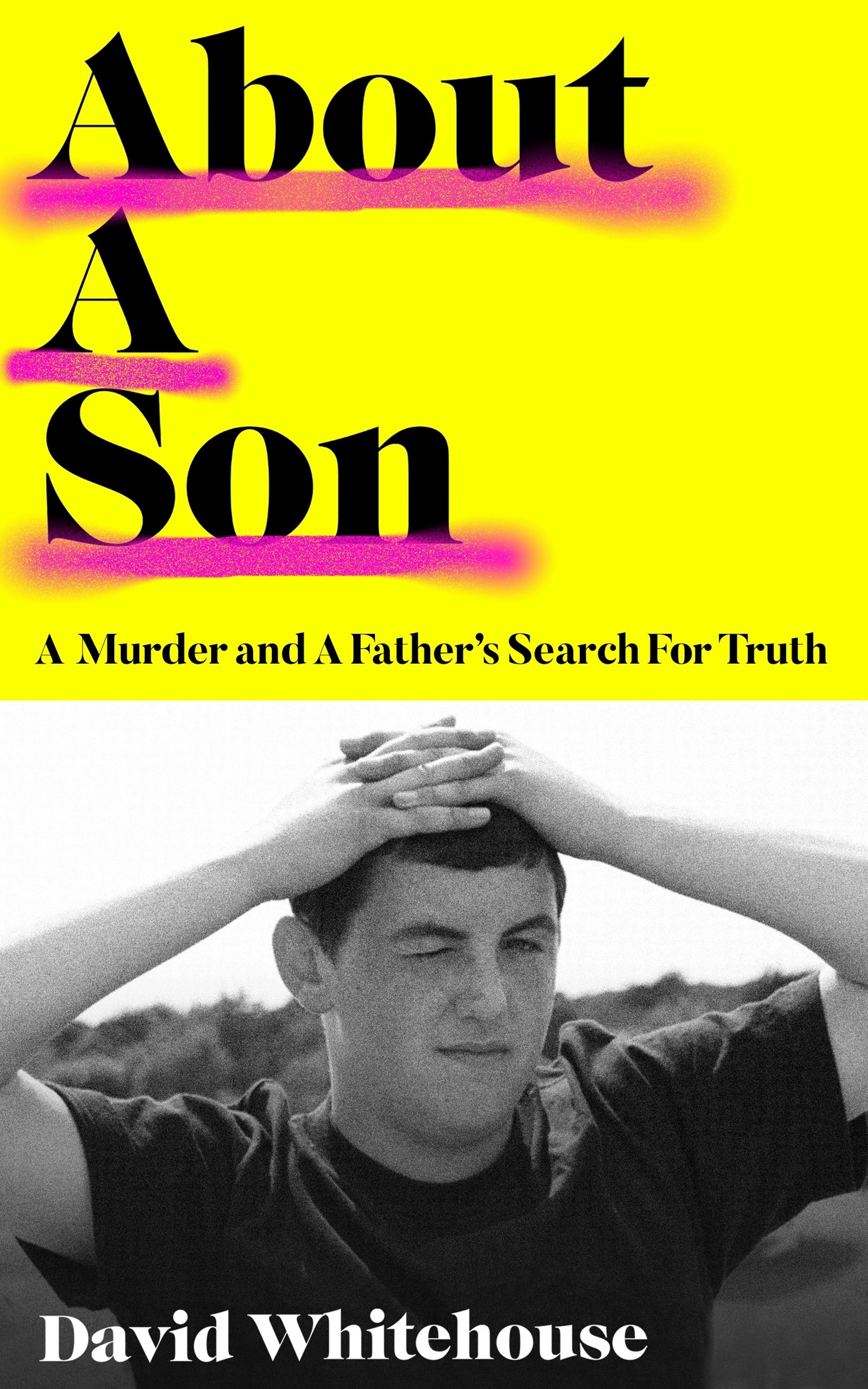

In the immediate aftermath of his son’s murder, Colin Hehir did something extraordinary. He began to write a diary of his unfolding grief and the struggle to understand the chain of catastrophic oversights that led to the events of Halloween 2015. This record forms the basis of About A Son, David Whitehouse’s remarkably inventive and compassionate new work of narrative nonfiction. Whitehouse, who grew up in Nuneaton, coupled the source material with extensive interviews with Colin Hehir. The resulting text is a unique blend of reportage and memoir: a ‘true crime’ narrative intensely focused on the left behind. It’s a tale of a bottomless love and pain, of life after the unthinkable has happened, as well as a portrait of a beloved, vibrant young man who barely had the chance to become himself.

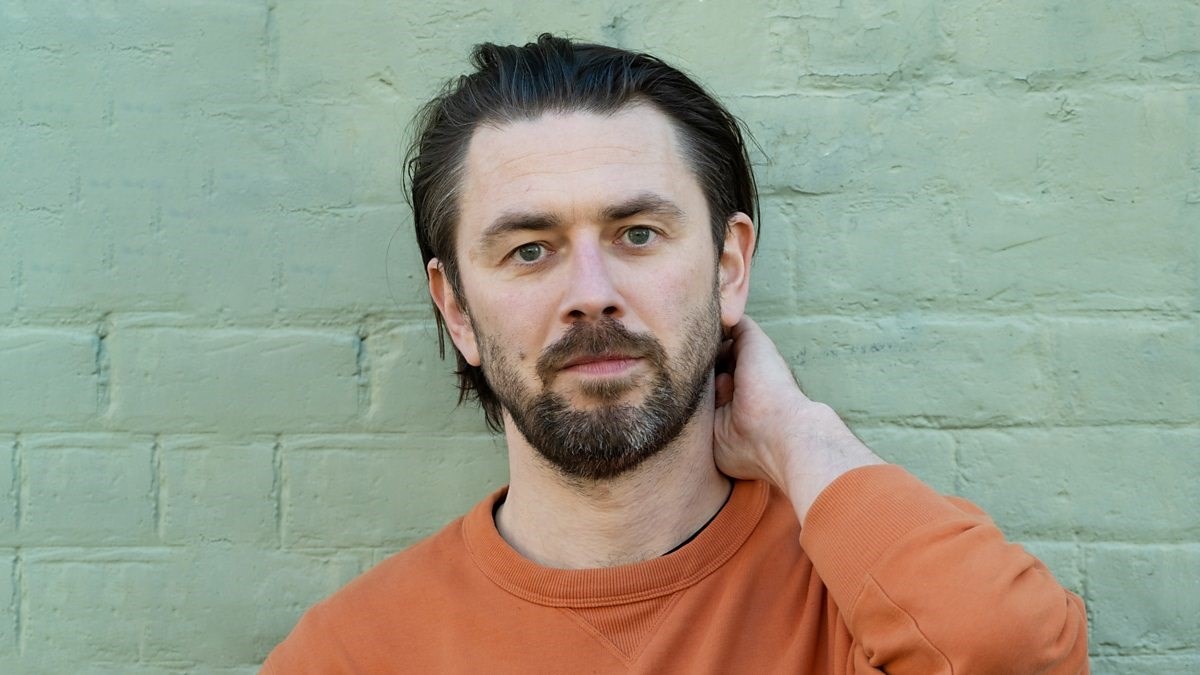

About A Son is composed entirely in the second person, a formal choice that makes for an extraordinarily focused intensity. The ‘you’ is Colin Hehir, and it is also us: the reader transported into the frontline of an immense and hitherto private grief. While deeply moving and humane, this is a work that also explores a simmering violence at the heart of British society. On a balmy spring afternoon in King’s Cross, I met David Whitehouse to discuss this remarkable book. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Francisco Garcia: Nuneaton isn’t the sort of place that features much in national debates around ‘youth violence’. In fact, it doesn’t really feature much in the national press at all. You grew up there and it’s where Morgan Hehir called home his entire life. You do a remarkable job painting a very clear-eyed portrait of the town, the loyalty it inspires as well as its problems. I was struck with the way it depicts – and this is by no means unique to Nuneaton – a very specific kind of small-town violence, both overt and hidden. Can we talk about that a bit?

David Whitehouse: Certainly in the mid-to-late 90s, when I was coming of age there, there was a culture of violence among young men. Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays were drinking nights in the town centre. The pubs were packed, and you’d always see fights. Real violence. People getting glassed and stuff. It’s only after you get older and leave that you realise how extreme and grim that is.

But that’s what it was. Violence was – I don’t want to say a way of life, it’s not Compton – but accepted and expected, something you got used to as a young man, and the town centre became a focal point for it. But that was then. Those pubs, or at least the ones that remain, are much less busy now, and with the death of the high street, maybe that violence has moved indoors, or into parks and parts of suburbia. Because bored, skint, poorly educated and badly cared for young men who’ve lived lives surrounded by violence, who use violence as a kind of currency, for whom violence is an everyday part of life – men like those who murdered Morgan – they still exist. They’ve just been hidden away. And, in the case of Declan Gray, allowed to walk the streets when they really shouldn’t have been.

“Colin allowed me complete access into his life and his grief, and in a radical act of faith gave me, a stranger, creative license to do what I wanted with it. The book was built from that trust” – David Whitehouse

FG: I don’t know if you’d agree with this term, but this really feels like a uniquely collaborative book. Could we talk a bit about that actual process between you and Colin, and how it came to be?

DW: I’d known about Morgan’s case already. When it happened, it’s the sort of thing you’re immediately sent by people you went to school with. I used to walk past the place he was murdered every day on my way to college. [Later] I received the diary through a friend of mine called Claire Harrison, who’s a journalist at the Nuneaton News. It’s a totally unique document, like nothing else I’d ever read. It’s so intensely personal, so open and honest. Colin wanted to know what he should do with it. His only motivation was to get Morgan’s story out there as widely as possible. [But] what do you say to a man who’s lost his son in that way? It was intimidating to have that conversation. I didn’t know how to advise him. It hadn’t crossed my mind that it might be a book I’d write.

Three months later, Colin got back in touch. It’s to my shame that I’d swerved having that conversation. He [contacted me] directly and asked what I’d thought of it. So I read it again and rang him, still not knowing what to say. So I told him that, and how it was one of the most [extraordinary] things I’d read in my life. It was the small details that really stuck with me, the banality of grief. Like how he and Sue couldn’t really watch television in the aftermath, because it held these constant reminders. Every other show was Murder She Wrote, or Midsomer Murders or whatever. [The diary] is a blow-by-blow account of the following years, with notes about [his] grief, totally raw and unfiltered.

After our initial chat we began to talk regularly, and I realised there might be a way to tell the story that showed Morgan’s death to not just be a state of the town murder, but maybe even a state of the nation one. For more than a year we spoke, texted, and even walked Morgan’s last steps together. Colin allowed me complete access into his life and his grief, and in a radical act of faith gave me, a stranger, creative license to do what I wanted with it. The book was built from that trust.

FG: It feels like the conversations around the ethics of ‘true crime’ have become increasingly stale, perhaps through oversaturation, or whatever else. One of the brilliant things with About A Son is how focus never shifts from Colin, or from Morgan really. ‘Victim centred’ is a pretty unlovely phrase – the memory of such a brilliant, vibrant young man could never simply be reduced to victimhood – though it’s probably a useful shorthand. Would that have been possible without the second person?

DW: I asked Colin if he’d let me try something and wrote the first section in the second person. It started to flow a bit more after that. I was thinking about Andrew Hankinson’s You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat], which is the best use of that voice I know of in non-fiction. What Colin did when he gave me his diary to read, was to put me totally in his shoes. The shoes nobody wants to be in. I couldn’t tell the story from his perspective. Only he could do that. But in writing his story in the second person, I could put anyone who reads it in those shoes. And maybe we might understand loss a little better as a result.

Also, it let me zoom out a little and tell the story of the town and the effects of tragedy upon it. I was thinking about Hankinson’s book and [also] about Gordon Burn, specifically parts of Happy Like Murderers. And I know how people from Nuneaton speak, I know what jobs they do and what their concerns might be. I know what it’s like to be skint growing up there. The second person felt like the way to tell the story. It struck me that the only way to [engage] with Colin’s diary was to have that dialogue with it: the book being a response to it, rather than just retelling the story of Morgan’s murder. Because it’s more than that. It’s [also] the story of a family’s grief and subsequent pursuit for justice.

“It struck me that the only way to [engage] with Colin’s diary was to have that dialogue with it: the book being a response to it, rather than just retelling the story of Morgan’s murder. Because it’s more than that. It’s [also] the story of a family’s grief and subsequent pursuit for justice” – David Whitehouse

FG: The systemic failures that lead-up to Morgan’s murder were shockingly crude. In the aftermath, it feels as if none of the relevant state bodies wanted to take even a portion of responsibility. Colin had to fight, for months, years, until the full truth was finally disclosed. I don’t know if ‘radicalised’ is the right way of putting it, but how do you think it changed his relationship with the parts of the state that we’re constantly reassured exist ‘to keep us safe’?

DW: Before Morgan’s murder, Colin was like most people – fortunate enough to not have any experience of the justice system. Even after Morgan’s murder, right up until the trial and maybe even beyond, he had faith in the system, certainly that it would work, and that what it was telling him was the truth. Because in the thick fog of grief, what else is there to cling to? You have to believe. But despite his grief, he somehow found the clarity to see that things didn’t add up. How could a young man with a history of extreme violence be free to kill his son? And when he asked these questions of the state, he was met with obfuscation. For years. It’s impossible to have total faith in the system after that. Hope, yes. But not faith. He’s not been radicalised, though I know what you mean, but he’s had his eyes opened. He doesn’t think the police or the people in charge of monitoring violent offenders are bad people. They made mistakes, big ones, but not on purpose. And yet his son is dead. How can he, or anyone else, believe the institutions charged with keeping us safe are fit for purpose after that? We think there is a safety net beneath us, but the truth, as Colin discovered because he was forced to look down, is that it’s full of holes. And that’s something we should all know.

FG: As you say, this isn’t a book that simply charts the facts of a terrible act of violence. What the Hehir family have gone through is unfathomable, for anyone who hasn’t experienced the same. There’s this unmistakable, clarifying anger that runs throughout. This is a book about deep institutional failure and those same institutions' denial of anything like culpability in the aftermath of Morgan’s murder. To what degree do you see this as a political text?

DW: To lapse into cliche for a minute, the personal is political. The only person responsible for Morgan’s murder is the young man who chose to take a knife onto the street. But he should never have been free or unmonitored. It’s impossible to not draw a line between the circumstances surrounding Morgan’s death, and what happens when the institutions in place to protect us are under-resourced and subject to austerity. These cuts result in preventable deaths at the hands of institutions which then, in failure, contort to protect themselves. And showing what that looks like in reality – it looks like Morgan – makes this a political text, I suppose. More than that though, it makes it a furious one.

That was an important motivation, really. The subsequent treatment of the family, by the police, by the criminal justice system, which, as the Hehir family experienced it, was never victim-led. Colin can and will talk about that all day. It's important that Morgan's murderers had a fair trial, of course. But Colin and his family had to negotiate to be given a seat in court for sentencing. And in the Miroslav Holan trial (Holan, a random passerby, had stolen Morgan’s iPhone and wallet as he lay dying), Colin had to fight to have his Victim Personal Statement read.

When they left the court after the [murder] trial, there was nobody outside. Your perceptions of these things come from what you see on the news. Journalists and microphones jostling outside. There was none of that. How do these things go, if not unreported, then untold? As soon as those trials are over what happens to those families? It’s not enough. Colin was consumed by it. You have to be to do what he did, to not give up for years trying to find out what [really] happened.

FG: This is a book that raises so many questions, some that are perhaps more immediately answerable than others. Is there, to put it quite crudely, a message you’d particularly like to be taken from it?

DW: That the Hehir family are just an ordinary family, and that something so tragic as this could happen to any of us, at any time. But also, I want people to know who Morgan was. A talented musician, a gifted artist, a great laugh, and someone who seems to me to have been loved by everyone who got anywhere near him. He’s much more than a knife crime statistic. I want people to remember him.