Jack Parlett discusses his new book which tells the story of Fire Island through the historical figures who spent time there and confronts its reputation as a utopia for the privileged few

After Noël Coward visited Fire Island in 1963, he wrote in his diary: “Never in my life have I seen such abandoned, concentrated sexuality. It is fantastic and difficult to believe. I really wish I hadn't gone. Thousands of queer young men of all shapes and sizes camping about blatantly and carrying on – in my opinion – appallingly.” This pearl-clutching verdict is one of many revelatory moments in Fire Island, Jack Parlett’s beguiling new book about the iconic vacation resort that has become synonymous with gayness in all senses.

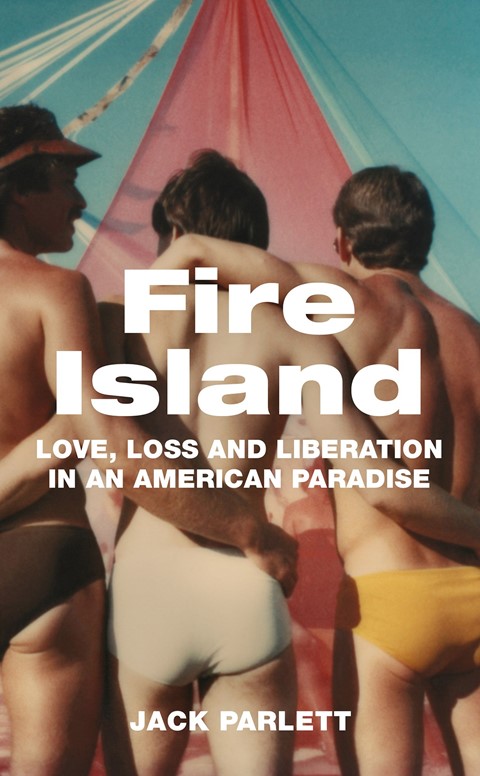

Parlett, a British writer and literary scholar specialising in queer studies and American literature, tells the story of Fire Island through the many prominent historical figures who spent time there – blissfully or otherwise – during the 20th century. In the process, he confronts its reputation as a hotbed of hedonism for the most privileged members of the LGBTQ+ community: white cisgender gay men with money and a particular body type. Parlett is clearly fascinated by Fire Island, an imperfect queer idyll that really has no UK equivalent, but doesn't let it off the hook. Here, he discusses his motivations when writing this critical love letter.

Nick Levine: This is a big question, but what is it about Fire Island that’s so endlessly alluring?

Jack Parlett: I think in part it has to do with the particular quality of the place. Like, it’s beautiful and so close to New York City, so from a vacation perspective, it’s just a really desirable location. But there’s something else going on, I think, in that it exists as both a real place and a mythic place. In part, Fire Island is speaking to a desire for a utopian place where queer people might imagine themselves to be at home and feel safe. It’s somewhere upon which we can kind of project our ideas of “the good life”. And because it’s built up gradually over the 20th century as a destination, it’s always been really alluring to new generations of queer people.

NL: What was your main aim in writing this book?

JP: I think my main aim when I began the research process was to embark upon a kind of literary history of Fire Island. I guess I wanted to look at all the writers who visited Fire Island and wrote about it, then use their experiences as snapshots of what the island was like in that period. But more broadly, I wanted to write a book that celebrates Fire Island for everything it has been, but doesn’t shy away from the thornier aspects. I think of the book as somewhere between a celebration and a critique; I don’t think those things need to be mutually exclusive.

NL: Do you think the very idea of Fire Island is triggering for some LGBTQ+ people?

JP: Oh, totally – and I would count myself in that category. That’s partly how I felt when I arrived there, and I say that with all the privilege of being a cis white gay man. Fire Island in the popular imagination is not a super-inclusive or accessible place. There are people for whom it represents all the exclusionary sides of LGBTQ+ culture: it’s seen as a utopia for the privileged few. So when I was writing this book, I did want to grapple with some of the stereotypes surrounding Fire Island. I think some of them are unkind and simplistic: like, the image of the entitled white muscle gay who doesn’t care about politics and doesn’t think intersectionally. Those stereotypes can be overstated, but at the same time, they don’t come from nowhere. Certainly, I found that when I was speaking to people about Fire Island, I got a very mixed response. It’s a deeply ambivalent place. For some people, it represents freedom. To others, it represents the opposite.

“ ... when I was speaking to people about Fire Island, I got a very mixed response. It’s a deeply ambivalent place. For some people, it represents freedom. To others, it represents the opposite” – Jack Parlett

NL: The cast of characters in the book is glittering: James Baldwin, Oscar Wilde, Frank O’Hara, David Hockney, Liza Minnelli and André Leon Talley all appear. How did you decide which figures to give weight to?

JP: Oh, it was completely dizzying. And there were moments where I was like, “How am I going to have space for Madonna and Cher?” But for me, it became less about the artists and celebrities who visited for a random weekend, of which there were many, and more about focusing on the figures who wrote about Fire Island. I mean, WH Auden wrote a poem about Fire Island. Andrew Holleran wrote a whole book [Dancer from the Dance]. So I was really thinking about the figures who contributed to something like a Fire Island canon. But it was also a challenge to decide whose voice to give a platform to. For example, Patricia Highsmith features in the novel and there’s been quite a lot of discourse recently about her politics, racism and antisemitism. So I guess I was trying to think about these figures in a microcosmic way – what were they doing on a particular weekend in the 60s – versus their larger legacy to the world, especially from a queer perspective.

NL: What do you see the future of Fire Island as being? As you acknowledge in the book, it’s a pretty precarious place in terms of its geographical position, which could make it vulnerable as the climate change crisis intensifies.

JP: I mean, obviously questions about climate change in the world far exceed this question. But even if it is unclear how long Fire Island will be around because it is precarious geographically, I will say that culturally, it seems to be in a process of renewal. I do think the communities there are future-oriented. They’re trying to invent an inclusive creative culture on Fire Island through residency programmes. From what I've seen from afar – because I haven't been there in a few years – they’re trying to make it a more welcoming place for queer artists of colour. But that’s not an easy transition to make and it’s going to take work. I think there's still a need for Fire Island, and that speaks to our continued desire to find liberation outside of everyday and heteronormative places. We absolutely need havens, even if they aren’t perfect.

Fire Island by Jack Parlett is out now via Granta Books.