Kathryn Ferguson tells AnOther about her new film, Nothing Compares, which charts the meteoric rise of a young woman from Dublin who was revered into megastardom but quickly reviled into exile

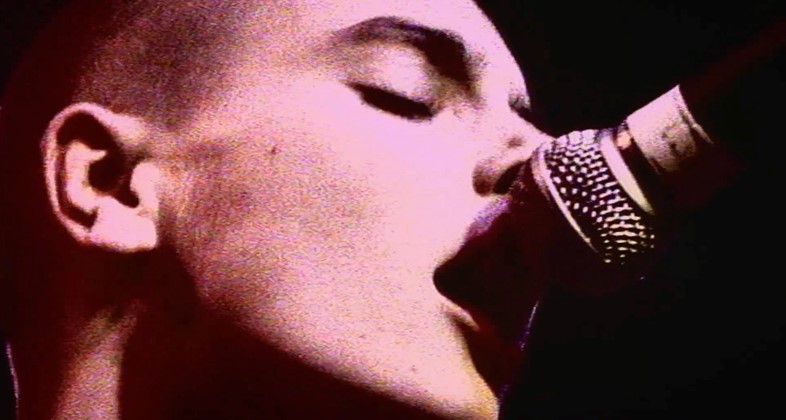

In 1992, Kris Kristofferson introduced Sinéad O’Connor on stage at a 30th-anniversary concert for Bob Dylan. “I’m real proud to introduce this next artist,” he declared. “An artist synonymous with courage and integrity.” She walked slowly onto the stage as the crowd erupted into an overwhelming and jarring concoction of cheers and boos. “It was the fucking weirdest noise I’ve ever heard in my life,” O’Connor says, while narrating a new documentary about her life, Nothing Compares. “It made me want to puke.”

This event came just 13 days after her infamous Saturday Night Live appearance, in which she ripped up a photo of the pope over an impassioned and impromptu version of War by Bob Marley, declaring “fight the real enemy” to an audience full of people stunned into silence. This moment of protest, in response to sexual child abuse in the Catholic Church, is an apex moment in the film, which covers a six-year period (1987-1993) spanning the meteoric rise of a young woman from Dublin to pop star and activist who was revered into megastardom but quickly reviled into exile.

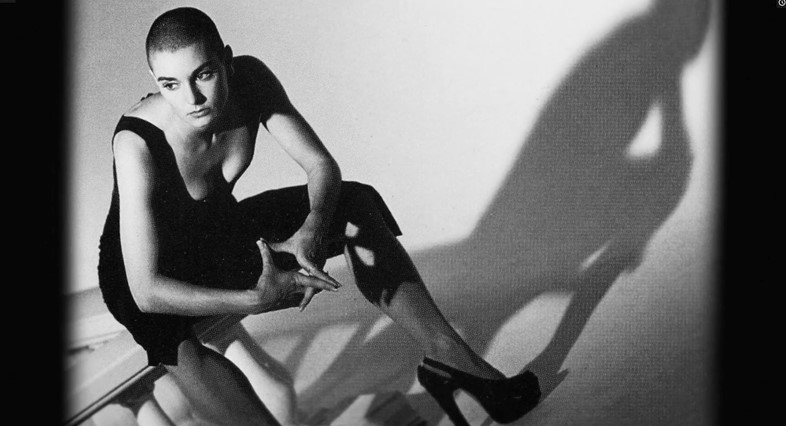

For director Kathryn Ferguson, who we caught up with after the film’s EU premiere at CPH:DOX in Copenhagen, O’Connor represented positivity growing up. “I was a bonafide fan,” she says. “I loved everything about her, what she stood for, how she looked, her lyrics, her boldness and what she meant to a young girl growing up in 80s and 90s Belfast. Things were a little grim there to say the least, with the Troubles still rumbling away in the North and the Catholic Church still very influential in the South, she represented hope. We all needed that.”

In the context of contemporary popular music, where political statements are relatively commonplace – often to the point of being performative, disingenuous or a form of marketing manipulation – the film paints a vastly different landscape via the 1990s music industry. One filled with coldness, hostility, rampant sexism and a cruel disregard for mental health; a time and place in which speaking out about such horrific, and since proven true, incidents wasn’t necessarily welcomed as brave or important but often belittled. “I was always being made out to be crazy by the media,” says O’Connor in the documentary.

In the wake of the SNL moment, Frank Sinatra and actor Joe Pesci both threatened physical violence towards her, she was mocked on primetime comedy sketches, including by Madonna, and her records were run over by steamrollers at Chrysalis Records’ Rockefeller Centre HQ in New York. Such was the deep-set hatred for her in some corners that one American TV pundit screamed during an interview: “In the case of Sinéad O’Connor, child abuse was justified.”

The crux of the film hits home the deeply fickle nature of fame and celebrity, and the ‘stay in your lane’ sexist mentality that underpinned so much of it. Within just two years, O’Connor went from being the hottest performer at the 1989 Grammy Awards to being ridiculed and lambasted by parts of that same audience. The whole world had fallen in love with a woman who famously shed a tear in the video for the global hit Nothing Compares 2 U, but was utterly indifferent to the reasons that may have caused it.

All of this follows an extraordinarily hard life that O’Connor had already lived. Her voice became a crutch from an early age when suffering abuse from her mother at home. “I was able to soothe her with my voice,” O’Connor says. “I was able to make the devil go to sleep.” When she briefly speaks about the song Troy, written about her experiences as a child of being locked out of the house and made to sleep in the garden for weeks on end, she describes it as “not a song, it’s a fucking testament”.

The film explores just how deep, and multifaceted O’Connor’s experience of trauma from childhood was, which made her journey to pop stardom an all the more difficult, and often perplexing, experience. “The reason I got into music was therapy,” she says. “Which is why it was such a shock for me to become a pop star. It’s not what I wanted. I just wanted to scream.”

Things didn’t necessarily get easier as O’Connor became a success. Her records were banned by American radio stations when she took a stand against the national anthem being played at a gig in 1990. When she got pregnant at 20, her label encouraged an abortion and refused to have her photographed in any press shots showing she was pregnant. “There’s no way I’m going to shut my mouth,” she declared. “I’m a battered child and the whole bloody world is going to know about it. The same as they’re going to know about every other battered child. They’re not going to be able to shut us up just because they don’t want to hear about it.”

O’Connor’s steadfast conviction in her beliefs, and the often-callous landscape that she had to fight against, came with huge costs for her, both professionally and personally, and Ferguson got to see this up close. “She has never wavered,” she says. “We’ve watched hundreds of hours of footage and she’s one of the most consistent humans that I’ve ever come across. She’s rock solid.”

From the shaved head to her distinct fashion sense and the subjects she so passionately spoke out on, from child abuse to abortion rights, the film paints O’Connor as something of a prototype for the pop-artist-as-activist figure, paving the way for future generations of young women. Contributors such as Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna, Peaches and Skunk Anansie’s Skin all credit her as a pioneer and outlier.

“She was very ahead of her time,” says Ferguson. “And in many ways a lone voice – or certainly an unsupported one. There seemed to be an overriding attitude that she should just shut up and sing. Here was this superstar with seemingly everything – the talent, the looks, the success – but the fact she also had a very strong point of view and wanted to be heard about unpalatable subjects seemed to be a want too many for some.” The most poignant line in the film comes from a defiant O’Connor herself who softly yet proudly declares: “They tried to bury me. They didn’t realise I was a seed.”

The impact of O’Connor’s treatment trickled down and even shaped a young Ferguson herself. “I felt very demoralised as a teenager when I saw how she was treated,” she says. “I think that feeling sowed the seed for this film. It felt wrong in 1992 and I still felt the reverberations of that when we started writing the film in 2018. I am still furious about it, and I hope audiences feel the same.”

Nothing Compares is in UK and Irish cinemas from October 7, 2022.