Ahead of his performance at the Serpentine Pavilion, Linton Kwesi Johnson talks about discovering Black literature, living through the colour bar in Britain, and why activism is more important than poetry

It is rare to find musicians like the British poet, activist and recording artist Linton Kwesi Johnson who are as committed to politicising their artistry as they are to living it out, through dedicating their life to grass-root mobilisation. We often see musicians sporadically hop on whatever wave of collective outrage is at the top of the news cycle to generate capital, but Linton’s work has never drifted away from the political. He has always stayed grounded.

Kwesi Johnson’s poetry and music have been the pulse of Black British activism for five decades. Ushering in the style of dub poetry, a blend of Reggae-tailored speech draped with the slick, ethereal sound of dub music, his contributions to the medium are irrefutable. Born in Jamaica in 1952 and later migrating with his father to Brixton, London in 1963, Kwesi Johnson joined the British Black Panther Movement while attending Tulse Hill School in Lambeth, facilitating poetry workshops while sharpening his craft with Rosta love, a group of drummers and poets.

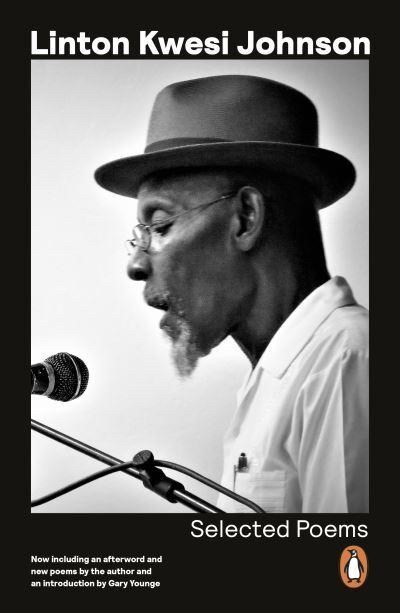

In 1974, Johnson’s poems first popped up in the journal Race Today – he later released his first LP four years later with Virgin. Since then, he has gone on to release over 15 albums and numerous books of poetry, and in 2002, he then made history when he became the only Black and second-living poet to be published in the Penguin Modern Classics series.

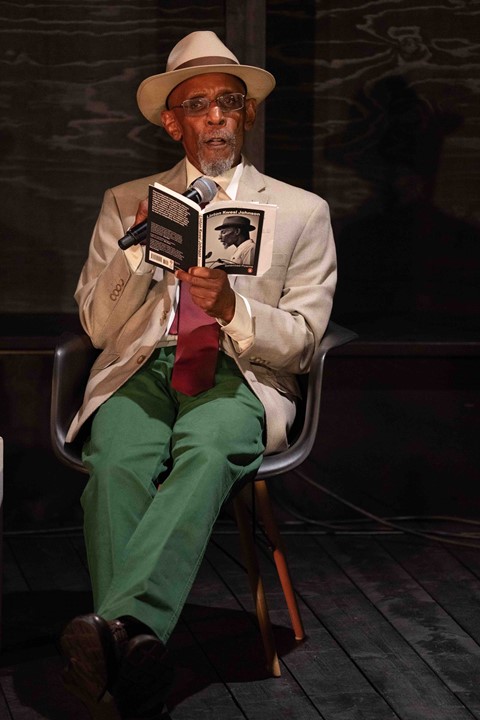

On Friday evening, Kwesi Johnson put on a performance alongside Caleb Femi at Theaster Gates’ Mark Rothko-inspired Serpentine Pavilion, Black Chapel. Upon entering the space, seats rapidly filled up with supporters and fans to watch his performance, forcing people to sit on the edges of the building – a clear hint of just how deep Kwesi Johnson’s poetry resonates. He approached the mic dressed in green chinos, a maroon tie, and a cream hat and blazer, and with his strong Caribbean accent, wasted no time slowly reciting his poems in a deep tone for all attentive ears to hear. “My generation changed Britain,” he says. “We were the rebel generation who refused to put up with the things our parents put up with.”

Ahead of his performance, AnOther spoke with Kwesi Johnson about Black literature, living through the colour bar in Britain, and why activism is more important than poetry.

Emmanuel Onapa: You joined the British Black Panther Movement at school. During your time there, you helped organise poetry workshops – why was that so important to you?

Linton Kwesi Johnson: It was a need for self-expression. I was young, and I had just discovered Black literature through reading a book called The Souls of Black Folk by WEB Du Bois – it was about the experiences of Black people in America after the abolition of slavery. The book made me want to articulate my generation’s experiences, you know? A few other people in the youth section of the Black Panther Movement were interested in literature. Some wrote short stories, some wrote poetry, and it was about four or five of us, and we would get together and exchange what we’d written with each other and discuss what we’d written.

EO: Do you think this country has made progress since your time as a teenage Black Panther?

LKJ: Oh yes, of course! My generation changed Britain. We were the rebel generation who refused to put up with the things our parents put up with. We would not tolerate the colour bar – that’s what they had at the time. You couldn’t go to certain places and do certain things if you are Black during that time. But through our rebellion, we broke down those barriers to integration and built political organisations and cultural institutions. We had an impact on British society. We’ve helped to improve this country, and we’ve changed ourselves in the process. We’ve made tremendous contributions in most areas of social and cultural life. I think it’s a measure of that determination to be treated as a regular citizen of this country rather than marginalised.

EO: One of your most known poems, Di Great Insohreckshan, was in response to the 1981 Brixton riots. What types of emotions and feelings were you going through that made you want to respond through poetry?

LKJ: That was such an exhilarating moment! I wanted to record and celebrate the moment because we were fighting – much bitterness had built up over the years because of how the police and the justice system treated us. And it was in the wake of the new crossfire, where 13 young Black children were murdered in a national attack at a party.

The uprisings weren’t limited to Brixton. Most inner-city areas in England exploded in Manchester and Birmingham, and all those places exploded. So what I was trying to do in that poem was to capture the moment, to celebrate it and to record it for posterity.

“We were the rebel generation who refused to put up with the things our parents put up with” – Linton Kwesi Johnson

EO: Would you say poetry is your best way of dealing with injustice?

LKJ: No, no, no, no! Not at all; it’s activism. It is not a substitute for concrete political action and going on the picket line. I’ve been a political activist since my late teens, from the Black Panther Movement to the Black Parents Movement, the Race Today Collective, and the New Cross Massacre Action Committee. All our struggles have a cultural dimension, but it’s not a substitute for taking to the streets when you need to make your voice heard.

EO: What are your future plans?

LKJ: I’m going to be 70 next month. I really like to have a chance to put my feet up, it’s just that people want to leave me alone. I’ve been trying to retire for the last ten years. At this stage in my life, I’m just taking things as easy as possible. I’m taking it one day at a time. But I’m still involved with the George Padmore Institute, an archive, and I’m the chairman of 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, an art gallery and learning institution based here in Brixton. It’s not like I have anything else to do with my time.

Linton Kwesi Johnson performed at the Serpentine Pavilion as part of the Park Nights series. Find out more here.