Nearly seven years in the making, Christopher Nelius’s new documentary examines the sweeping sexism that pervaded surf culture in the 1980s and 1990s

A few days before I meet Australian director Christopher Nelius over Zoom, England beat Germany 2-1 in the UEFA Women’s Championship at Wembley. Rightfully celebrated by football fans and politicians alike, it’s not long before online discourse taps into the financial discrepancies between these women and their male counterparts. The following day at a London book launch, an editor points out that the women had to literally win the tournament to receive the recognition. Girls Can’t Surf, Nelius’s new documentary examining the sweeping sexism that pervaded surf culture in the 1980s and 90s, subsequently feels very topical. “It’s a great demonstration of just how hard women have to work to be taken seriously,” he remarks of the feature, inadvertently echoing the editor’s sentiment.

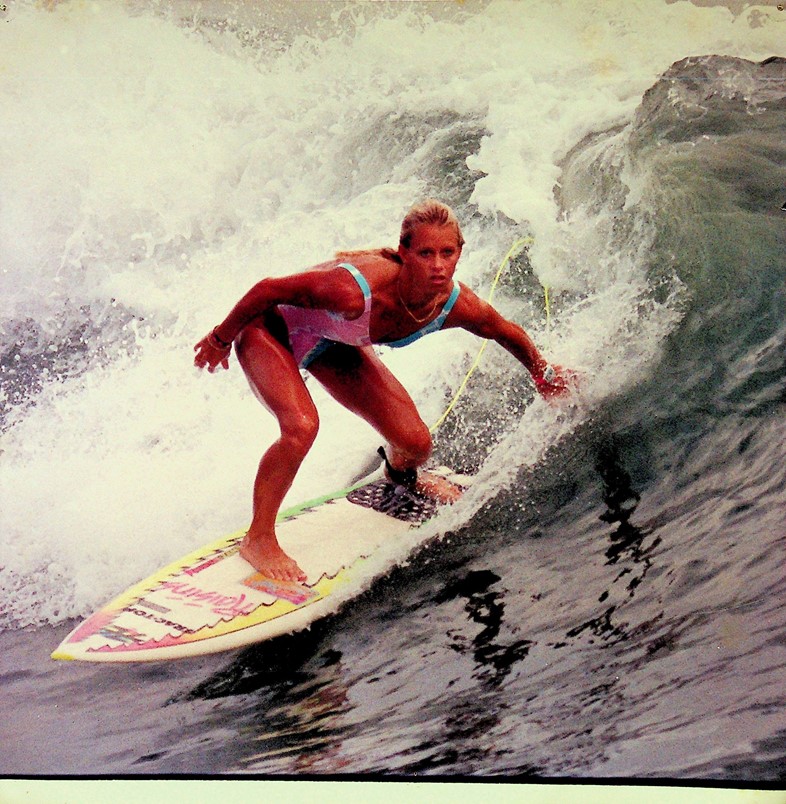

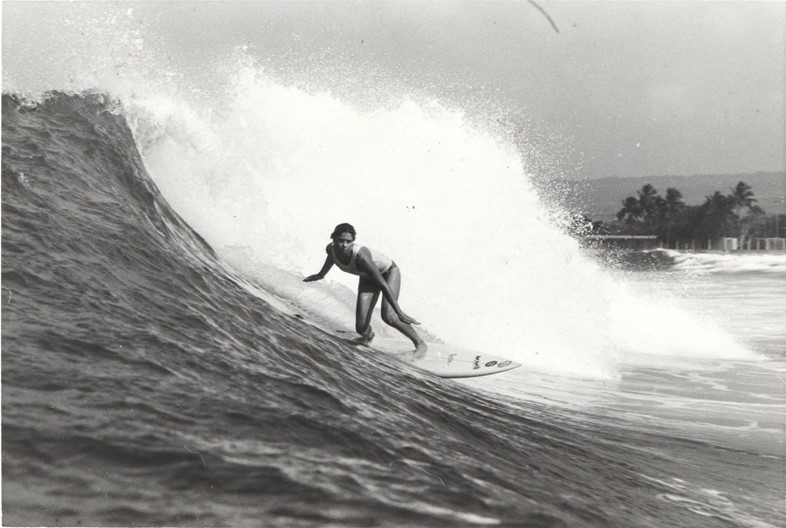

Nearly seven years in the making, the documentary couples present-day interviews with legendary pro-surfers – Pam Burridge, Pauline Menczer, Jodie Cooper, Wendy Botha, Lisa Anderson and more – with archive footage from early tours. Nelius says he became immersed in the storytelling and myth-building culture that surrounded male pro-surfers while working with Ross Clarke-Jones and Tom Carroll on the documentary series, Storm Surfers. “They’d tell me these crazy stories about what an anarchic, loose sport it was, and about trying to get money to go from here to there. Somewhere along the line, I thought, ‘If these guys were scrimping and saving, how the hell did the women do it?’.” Witnessing a gendered change in the surf demographic at Bondi beach further solidified his need to make the film. “That’s real social change, right in front of you. I wanted to know how that happened.”

When Nelius first began reaching out to the women who appear on screen – each of them a world record holder at one time or another – he was met with a largely cagey response. “That generation has been burnt a lot,” he explains. “So some of them were like, ‘What do you want to know this for?’ and others were like, ‘We’ve been waiting 20 years for someone to tell this story’. I describe them all as superheroes who’ve hung up their capes, and so it was a matter of them having to dig back into their memories. I think [a lot of them] felt like they’re at a point where they can speak the truth, say what they want to say, and feel supported by the fact that society has changed.”

The archive footage details this change, with early clips harnessing the gross attitudes of the time (in one, Australian pro-surfer Damien Hardman tells the camera, “They just need to look like women, look feminine, look attractive and dress well”) and later sequences highlighting the changes that followed, like the arrival equal pay in 2018. Personal stories of homophobia, poverty and eating disorders offer a further picture of the distress experienced in pursuit of dreams, while the film’s title reflects the era’s wider thinking. “It’s clearly a pretty provocative thing,” acknowledges Nelius, who worked closely with the writer and editor Julie-Anne De Ruvo, “but it also gets to the crux of what the film is about.”

Despite depicting feminism at work, the term is barely uttered in the documentary (or its accompanying marketing). Mostly says Nelius, this is because the group – whose collective actions were the genesis for how the sport operates today – didn’t consider themselves part of the movement. “None of them were feminists with a capital F. They were just young athletes with stars in their eyes, wanting to be world champions. There was nothing really political about them, even Layne Beachley and Rochelle Ballard, who became these political forces within the industry, didn’t start out that way,” he explains. “I describe them as unlikely feminist heroes. They discovered that ‘oh, this dream doesn't apply to us, it only really applies to the men’ and met the challenge head-on by pure instinct of character. I feel like they probably didn’t understand their own significance until the surfing body announced equal prize money.”

“There’s a lesson to be learned about how social change happens,” Nelius continues, reflecting on a particularly significant moment when heavyweight surf brands embraced their female audience and introduced new gender-specific lines, ultimately affecting little change at the top. “I was blown away. Roxy started the Roxy revolution, straight away selling more women’s clothing than men’s, and I thought then it would have changed, but it didn’t. The image of women’s surfing was propping up a lot of the surf world with the money generated, but it was still the men that were making the decisions. That was cruel, and I learned a big lesson of just how bloody hard women have to work.”

Girls Can’t Surf is out on 19 August 2022.