As they embark on their 50th anniversary tour, we look back on Roxy Music’s iconic album artwork – which featured models as idealised statues, walking a line between sexualised commodities and unattainable, Amazonian goddesses

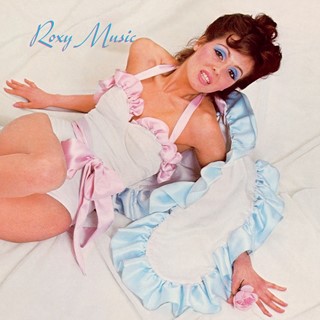

In 1972, models didn’t grace album covers unless it was a Top of the Pops compilation. The first Roxy Music sleeve, featuring Kari-Ann Muller in baby-blue eyeshadow and trussed up in a pink bow, was a provocation, a postmodern allusion to style over substance at a time when rock was awash with denim and earnest authenticity was the order of the day. Exacerbating the situation further, the gatefold sleeve carried credits like a style-mag fashion shoot: “Kari-Ann’s hair by Smile”; “Clothes, make-up & hair by Antony Price”... Along with David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album, released on the same day, it announced that sex was back.

“When I first went to London in 1966, it felt like the 1950s hadn’t really gone away,” says Brooklyn-born photographer Karl Stoecker, who found the UK capital more antiquated than its swinging reputation suggested. “So I started thinking, ‘Oh, who was that illustrator who used to do those pin-ups?’” Stoecker began shooting real-life models based on Alberto Vargas’s Esquire illustrations series that ran throughout WWII. Stoecker’s preferred models were Kari-Ann Muller, Gala Mitchell and Amanda Lear.

“They’re all really good,” says Stoecker. “They knew what to do. They’re not just standing there saying: ‘Where should I put my hands?’ I mean, everyone was taking acid in those days and we were all kind of on the same page.” The photographer remembers working in a creative milieu where everyone was willing to experiment and nobody was getting paid very much. Crucially, he was working in tandem with emerging British fashion designer Antony Price, who was working for ‘King of the King’s Road’ Ossie Clark at the time. “Antony is absolutely amazing, and what I often think is: I’m just there with a camera to take the picture.”

Roxy Music’s frontman, Bryan Ferry, sought out Price after seeing the results of the shoot he and Stoecker had done with Muller. Stoecker took more shots with Price in situ for the sleeve, and the one that was chosen for the cover was a replication of one of their earlier Vargas homages. “I was paid 500 quid or something like that,” says Stoecker, laughing. “I met the drummer Simon [Kirke] from Bad Company, who’s from across the street from us in Miami. And he said to me, ‘£500? Man, our guy got paid £10,000!’”

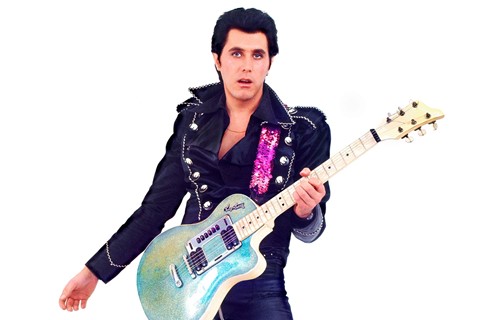

Stoecker was also the man who did the band portraits for the first three albums, Ferry an ersatz image of crooner-like perfection, Eno resplendent in feathers like some rare bird of paradise. “Eno was the one I hung out with the most,” he says. “I gravitated towards [him] because he was pretty wacky and into The Velvet Underground and John Cale.”

Price, meanwhile, struck up a close bond with Ferry; the two had much in common. Both went to art college and grew up in relative poverty in the north. “We were fucking penniless!” says Price on a Zoom call from his office. “I lived on a farm in the Yorkshire Dales with no electricity and water that froze up in winter and dried up in summer.” Price was to become Cecil Beaton to Roxy Music’s My Fair Lady, to borrow a phrase from rock critic Michael Bracewell. He still works with the rock star now in an advisory capacity. “Let it be understood that Mr Ferry knows damn well what he wants and always has. End of!” says Price, emphatically. His well-enunciated Yorkshire vowels make much of what he says emphatic.

Ferry studied under pop-art founding father Richard Hamilton at Newcastle University and, while he didn’t pursue painting, it was while working as a ceramics teacher in London in the early 1970s that he realised he could express his artistic ideas through music, and impose his vision on a band using the same montage techniques as his mentor: 1940s pin-up girls, 1950s leopardskin and doo-wop, 1960s psychedelia and music from the future courtesy of Eno’s EMS VCS3 synthesiser and tape machines, all converging in a highly stylised way.

Roxy’s models are idealised statues, walking a line between sexualised commodities and hyperreal, unattainable, Amazonian goddesses, free from imperfection. Nowhere is this more apparent than on the cover of For Your Pleasure, which stars Amanda Lear – a muse to Salvador Dalí and later a successful disco singer in her own right – with a heavily sedated panther on a leash and Ferry on the back sleeve dressed as a chauffeur. “I had no idea what they were gonna do on that one,” says Karl. “They just said, get a studio big enough to hold a car, then I had to scramble around to get enough black vinyl to cover the floor.”

Playboy model Marilyn Cole posed for an Eno-less Roxy Music on 1973’s Stranded, with Stoecker presented with a vague theme. “So we need this Tarzan girl lying in the jungle,” he says. “Jungle? Jungle? What the fuck do I do?” The photographer rushed down to Ealing Studios and borrowed some props, including a rubber tree. “I got some other pieces from them, including some grass, and then I went around to all the florists and got flowers and plants and stuff that I thought would look like a jungle. I’d never been to the jungle so it was kind of like Rousseau – all those jungle paintings and he never left Paris.”

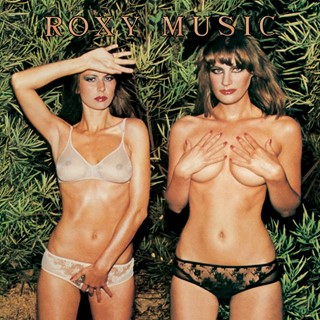

Stoecker moved back to the US in 1973, and three photographers shot the remaining album sleeves: Graham Hughes, Eric Bowman and Neil Kirk (Bowman and Kirk both died in August of this year). Bowman was on hand for Country Life, when he, Price and Ferry went on holiday together. That iconic shot of two demi-clad models lying on the grass happened in the moment, according to Price: “We all went down to the south of Portugal and found these German girls Constanze [Karoli] and Eveline [Grunwald]. Goddesses! Fantastic, those two girls. German, amazing, amazing!”

Texan model Jerry Hall was brought over to Britain to shoot 1975’s Siren. She was living in Paris in a flat with Grace Jones, Jessica Lange and Antonio Lopez at the time. “Can you imagine?” says Price, raising an eyebrow. “Between them they formed the 80s. This was in the 1970s, and they’re all on the way up.” Price cased out a site in Wales with EG Records’ Nick de Ville after seeing a documentary on the BBC about rocks. Hall was painted all in blue, and after the crew hastily dispatched some distracting orange canoes floating off the rocks of Holyhead, the shoot went swimmingly. “Those pictures are magnificent,” he says.

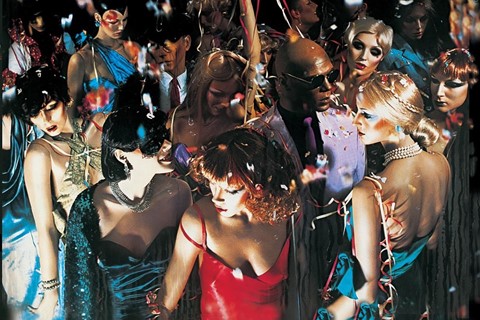

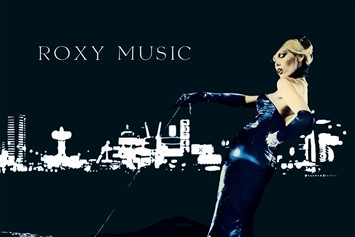

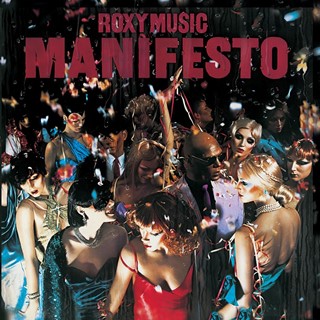

Roxy Music took a four-year breather and, when they returned in 1979, they were a very different-sounding band, more smooth soft-rock than art pop. A visual shakeup was in order, too, on Manifesto, which featured a party of mannequins – an attempt, perhaps, to subvert their own aesthetic (and slyly reference In Every Dream Home a Heartache, an ode to a rubber doll). The typography on the album is a tribute to British futurist artist Wyndham Lewis, a legend in his own time who famously tarnished his reputation with his early support of the Nazis. 1980’s Flesh and Blood, art directed by Factory’s Peter Saville, possesses the creeping menace of a bas-relief on an EUR monument, or the Olympic Nazi propaganda of Leni Riefenstahl. It could all be interpreted as a bit sinister.

Antony Price dismisses such talk: “[Flesh and Blood] was supposed to be Olympian more than anything. I don’t know where Bryan got the idea from.” Regarding the models, he says: “Obviously, guys were turning on to those images, and a lot of Roxy fans were straight, heterosexual guys. It’s probably something today where all those sorts of people would come down on you. We’re not allowed to have fun anymore, are we?” It’s a strange take, given the landscape Roxy Music came into, where the market decreed album covers should feature denim-clad longhairs (Deep Purple, ELP) solo artists lost in reverie (Stevie Wonder, Tom Waits) or abstraction with a name slapped on the front (Yes, Neil Young, Chicago). Against all that, Roxy’s sleeves possess the carefully layered eroticism of a Helmut Newton nude, images of decadent glamour that double as critiques of fashion’s economies of desire. It’s the same mirage of perfection Ferry is chasing in More Than This or In Every Dream Home a Heartache.

Price’s favourite cover is 1982’s Avalon, when Roxy Music went out with an inadvertent bang. Shot by the designer himself, it features model Lucy Helmore aboard a stygian barge with a raven on her shoulder, surveying an Irish lake at dawn. The funereal calm was more an accident than by design. “That was a wonderful shoot,” sighs Price. “There were supposed to be fireworks, but then this joke firework got in the box and the whole thing went up and exploded.”

Thanks to a social mobility that has now all but disappeared, Price and Ferry were able to join what has been described as a “classless aristocracy”. Ferry once described himself as “an orchid born on a coal-tip”, and I wonder if Price – a man who helped invent the 80s himself, dressing David Bowie and Duran Duran – ever felt the need to reinvent himself. “I had no desire,” he says, brusquely as ever. “The only part of myself I wanted to recreate was how I look. That’s how you end up in fashion. You are dissatisfied with what you see in a mirror and you set about altering it.”

Find out more about the Roxy Music 50th anniversary tour here. Discover more of Karl Stoecker's photography on his website and Instagram