As his new film Crimes of the Future is released, Alex Denney offers a brief introduction to the Canadian director’s mind-boggling oeuvre

With Crimes of the Future, David Cronenberg returns to the genre he is often credited with single-handedly inventing: body horror. Through the first two decades of his career, the Canadian director pioneered a new cinematic language that, though technically rooted in horror, opened up new lines of inquiry on the fleshy prisons we inhabit. These films were philosophical texts masquerading as exploitation, dreaming up mutant futures for humanity in which cancerous growths become psychic organs, cars become erotic extensions of the body, and viruses become colonising forces that undermine our assumptions about the self as an inviolate entity.

Of course, like all good prophets, Cronenberg is no stranger to heresy. His breakout third film, Shivers, was debated in Canadian parliament for its corrupting effect on society. Two more early works, Rabid and Scanners, were swept up in the ‘video nasties’ scandal of the early 1980s; and Crash, his mirthlessly pornographic rendering of JG Ballard’s novel of the same name, was subjected to a relentless ‘ban this filth’ campaign by the Daily Mail and Evening Standard: to this day, it remains banned in the London borough of Westminster.

But it’s Cronenberg’s willingness to meet the taboo on its own terms that gives his body-horror films their transgressive power. In fact, ‘body horror’ is an odd term for the work of an artist who seems fundamentally ambivalent about the transformations his characters undergo. A cancer, after all, is a mutation that is often associated with a death sentence: but mutation is also the key to our evolution as a species, even if the overwhelming majority are at best, neutral, at worst, actively harmful. Could death just be one more mutation of a kind? Cronenberg is too much of an atheist to answer that question, but the thought lingers at the edges of his work.

For the uninitiated, we looked at five essential films in a mind-boggling oeuvre that is, to quote Léa Seydoux in Crimes of the Future, “juicy with meaning”.

The Brood, 1979

There are divorce movies, and then there’s The Brood: conceived in part as a kind of deranged commentary on Cronenberg’s fast-unravelling first marriage, it’s a work of free-flowing madness that leaves an undeniably bad taste in the mouth. And it’s really, properly scary. In the film, Frank Carveth (Art Hindle) fights for custody of his daughter with his ex-wife, Nola (Samantha Eggar), who is engaged in an experimental form of psychotherapy which – wait for it – may somehow be linked to a wandering band of mutant kids who’ve recently begun bludgeoning the local townsfolk to death. Sometimes overlooked in favour of Scanners, another early work of balls-to-the-wall body horror, The Brood gets our vote for its autobiographical streak: it’s perhaps his most personal film, and certainly his nastiest.

Videodrome, 1983

Cronenberg’s big hit of 1983 was The Dead Zone, a disappointingly tame adaptation of a Stephen King novel starring Christopher Walken. But the one that endures is Videodrome, an explosive distillation of his themes to date that explores technology’s potential to remake humanity in its own image. The plot sees sleazy TV exec Max Renn (James Woods) become obsessed with an illicit S&M transmission called Videodrome, brainchild of a mysterious ‘media prophet’ called Brian O’Blivion. During his enquiries, Max begins to experience powerful hallucinations, developing a vagina-like orifice in his chest that accepts cassette recordings of Videodrome – which, depending on who you believe, is either the next chapter in human evolution or a form of mind control soon to be unleashed on the wider public. It’s fully bonkers stuff, an unholy marriage of Guy Debord and HP Lovecraft for the video age, and you have to wonder if the young Wachowskis were taking note, as they took many of the same themes to the multiplex 15 years later with The Matrix.

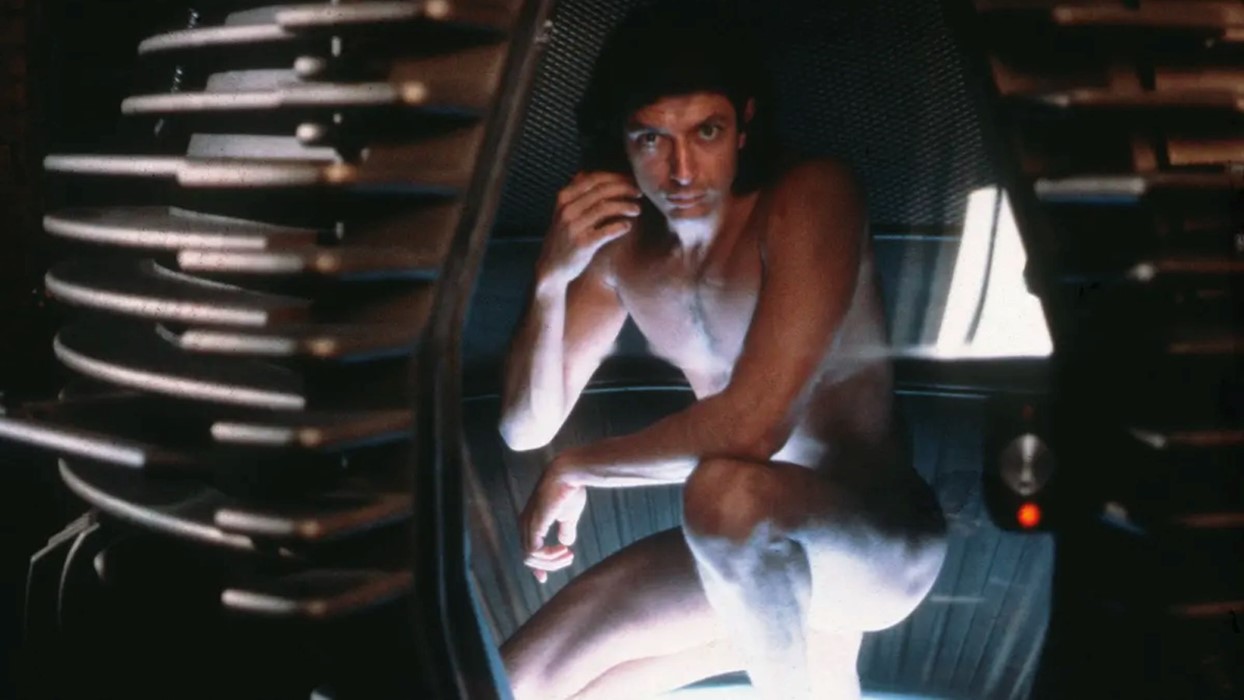

The Fly, 1986

Despite pushing the gory stuff to new heights of grand-guignol excess – Jeff Goldblum vomiting a man’s hand off is a childhood memory I’ll never forget, for better or worse – The Fly is the film that marks the maturation of Cronenberg’s style and themes. Adapted from the 50s B-movie shocker of the same name, the story follows scientist Seth Brundle (Goldblum), who accidentally fuses his DNA with that of a housefly while experimenting with a teleportation device he’s invented. The premise is both pure shlock and classic Cronenberg territory, a typically icky metaphor for disease and ageing that struck a chord with filmgoers at the height of the Aids epidemic. What really elevates it, though, is Brundle’s tragic romance with Geena Davis’s character, Veronica Quaife, a rare glimpse of love in an oeuvre whose clinical outlook often precludes such niceties.

Crash, 1997

Twenty-five years on from its release, Crash can still make for a seriously unpleasant ride, its mix of chrome-plated soft pornography and deep self-seriousness (“Describe his anus to me”) practically daring you to turn it off. But this chilly, hypnotic take on JG Ballard’s work of auto-erotica is also the film that, alongside Videodrome, comes closest to articulating Cronenberg’s MO as an artist. Its ability to provoke and inspire debate is perhaps best summed up by the film’s reception at Cannes, where the film received a Special Jury prize for artistic daring, despite Francis Ford Coppola’s best efforts to veto the award. The late Bernardo Bertolucci, meanwhile, described it as a “religious masterpiece” – an odd description for a film about people who like crashing cars and fucking in the wreckage, but we’re not going to disagree.

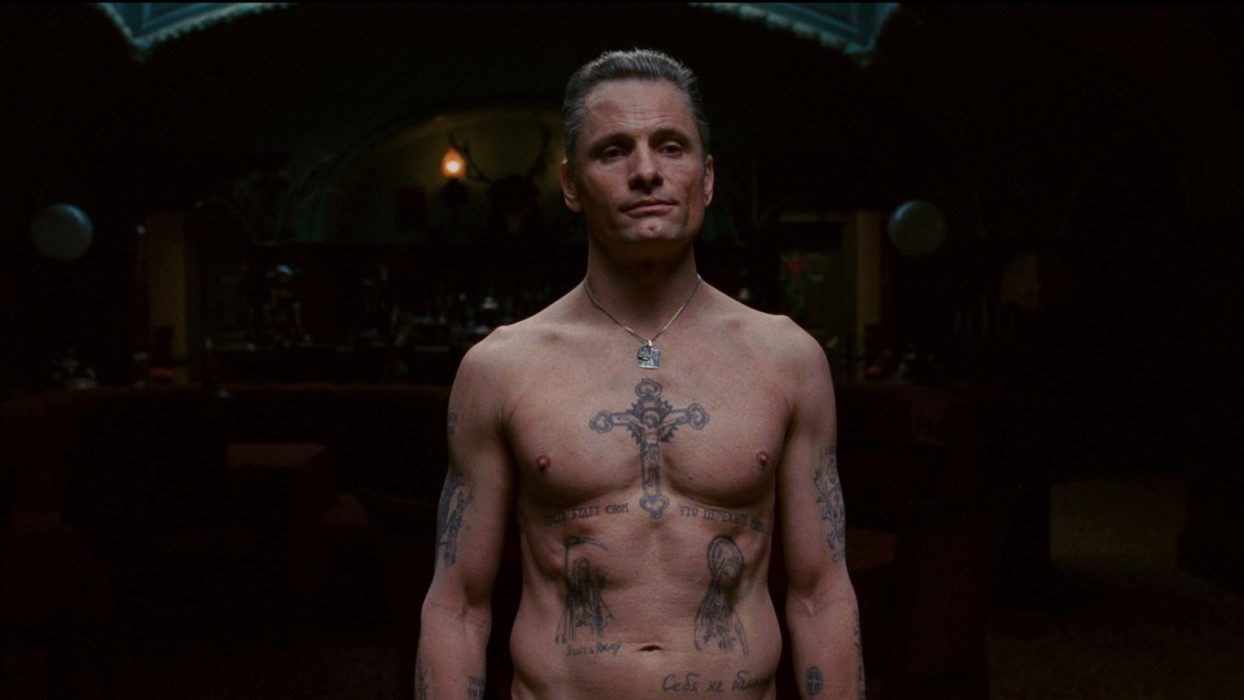

Eastern Promises, 2007

The mid-00s were a bit of a renaissance for Cronenberg, who embarked on a decades-long collaboration with Lord of the Rings star Viggo Mortensen in A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, two thrillers that comfortably rank among his best, and certainly most accessible, work to date. The former is perhaps the more philosophically minded of the two, a Peckinpah-esque story of a small-town family man forced to confront the killer inside him when the mob turn up at his door. But it’s Eastern Promises we’ll plump for here, a Russian mob drama with timely resonance and some fantastic local colour (it was shot amid the battered store fronts and crumbling Victorian facades of east London, then on the cusp of gentrification). Is it a superior hack job, or a Cronenberg film in the truest sense? Perhaps a bit of both: but in its Freudian overtones and lingering appreciation for Russian gangland tattoos, life stories inked upon bodies, there’s plenty to chew on in this taut, multilayered thriller. And that’s before we even get to a certain starkers fight to the death in a Turkish bathhouse.