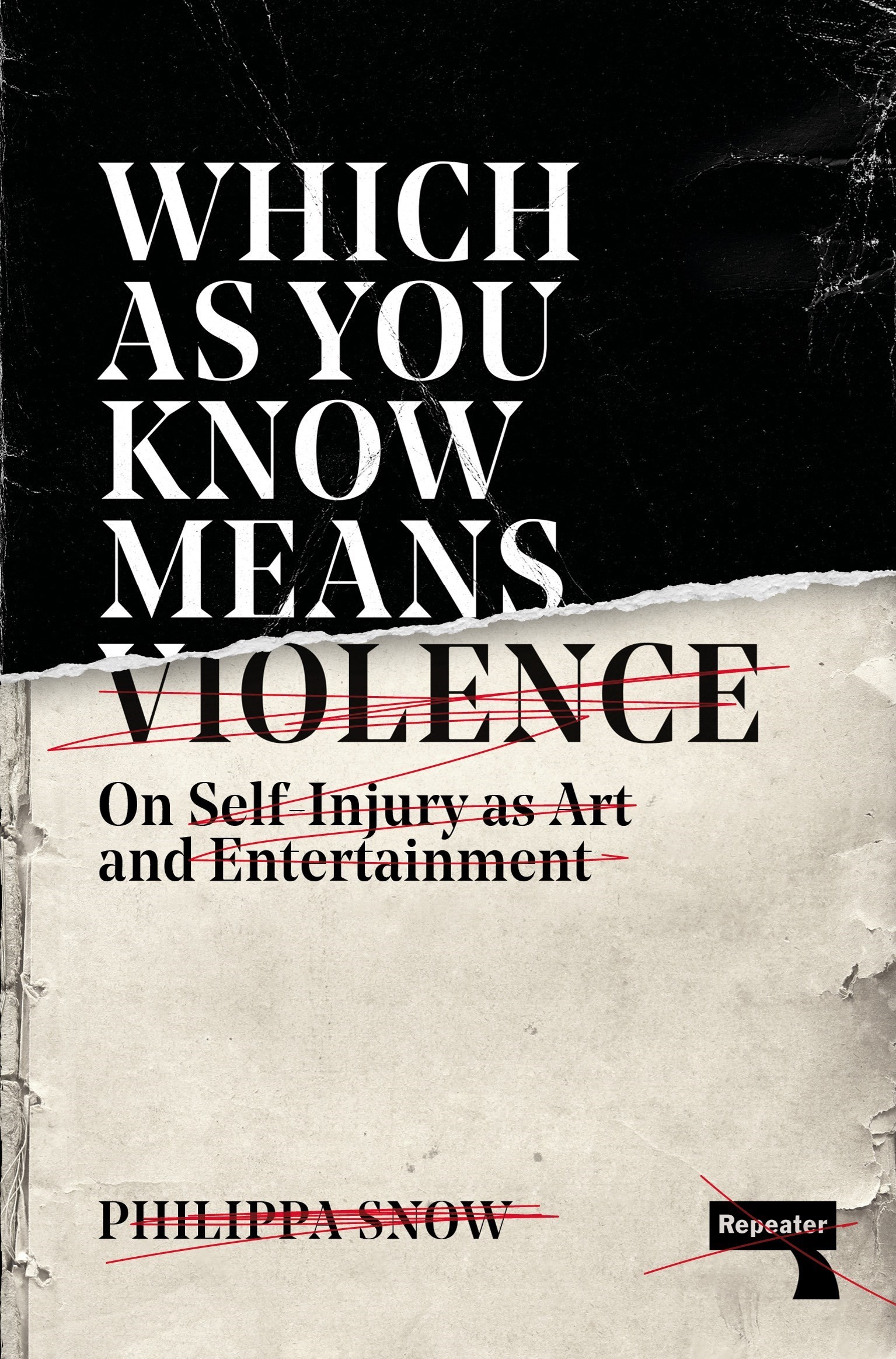

There is a throwaway line in the second chapter of Philippa Snow’s debut, Which As You Know Means Violence, – “art can be an accident” – which acts as a neat explainer on the roving approach of a remarkable, original book, that opens with a close reading of Jackass. (The phrase “which as you know means violence” is borrowed from a message the writer Hunter S Thompson left on Johnny Knoxville’s answering machine in the weeks before Thompson died). Moving deftly through artists including Chris Burden, Ron Athey and Nina Arsenault, YouTubers, the director Harmony Korine, Buster Keaton, and many more, Snow considers the relationship between pain, self-harm, performance and life.

Though this is her first published book, as both a critic and essayist Snow is prolific, with bylines in Artforum, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Frieze, Vogue and many more. Her writing has a singular quality: one of the pleasures of reading her is that certain fixations – Lindsay Lohan, the films of David Lynch, the bind of heterosexuality – repeat, so that her work has a particular Snow sensibility.

She feels like a writer’s writer. “Philippa’s writing makes me feel like I am rolling around in the mud wearing pearls. You are in the muck of glamour!” says the fashion journalist and critic Rachel Seville Tashjian. “I can think of few people writing now who give ‘the great feminine’ the kind of gritty and glorious thinking it deserves, which is what Philippa does.”

Which As You Know Means Violence is a surprisingly moving, life-affirming book, in part because it’s about life, art, performance, being pushed to its limits. Here, we discuss the current landscape for criticism, subconscious creativity, and the value of humour.

Holly Connolly: What I love about your work as a critic is that you’re able to find meaning and value in both ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, so that your criticism often adds a new depth or dimension to the work itself. What do you think the role of the critic is?

Philippa Snow: What a thoughtful and terrifying question! As to the purpose of criticism in general, I suppose I’m not sure I could simplify it into a single answer – I find it easier to talk about my own relationship with it as, if you’ll pardon the pretension, an ‘art form’, than to address it as a whole. I will say that my background is in art rather than academia or literature, and at one point I had the idea that I wanted to be an artist; what I found studying at art school, however, was that I tended to be more interested in either fleshing out the explanation behind what I was making, or dissecting the work of other artists in order to tease out meaning. I think it’s fair to say that, for me, that’s what criticism is – it’s about disassembling the art object in order to figure out how it works.

The internet has royally fucked with things in some ways, because as far as I can see it’s far easier to reach a wide audience with a pan than it is with a positive review; I also think most critics will admit to finding it less challenging to write about something they hate than something they love, because writing cruelly is easier than writing kindly. I’d also like to say on the record that I have a policy about not writing an acerbic review unless I feel I’m punching up: I wouldn’t sharpen my knives to go in on a debut book by a young author, for instance.

“That’s what criticism is – it’s about disassembling the art object in order to figure out how it works” – Philippa Snow

HC: You very effectively break down the line between, say, performance art and the performances in something like Jackass. How do you decide something is a worthwhile subject?

PS: I’m sure there are a lot of writers who have very strict ideas about what is or is not their terrain as far as a subject or a theme is concerned, just as there are writers who have very defined ideas about what they invariably refer to as their ‘practice’. The stupid but truthful answer is that I tend to choose subjects based purely on feeling – either I have a connection to them that I often find difficult to express other than through the criticism itself, or I’m struck by the possibility of extrapolating some sort of greater meaning or message about culture or society or gender. Increasingly, the merging of high and low culture is seen as a fairly standard way to write as a critic; it’s always been my preferred mode, and luckily there are now more opportunities for me to work in that arena without editors thinking I am insane.

I also have to add that, because I wrote this manuscript in the period after contracting Covid when I was really quite seriously ill, I will be the first to admit that there is a formlessness to it because it emerged at a time when I was sort of a stranger to myself, physically and psychologically, and when I was experiencing quite severe brain fog intermittently. Reading it now, it often feels to me as if somebody else wrote it, but I have to say that the illness in some way loosened or destructured my thinking, so that a lot of the decisions I made were based on instinct rather than any preconceived ideas about what the finished book might look like.

HC: I find the word ‘formlessness’ interesting, because it struck me that Which As You Know Means Violence has this quite subtle narrative arc. It opens with a focus on teenage-adjacent, ‘harmless’ pranks, but by the last chapter is very focused on death. To me it felt that the book followed the arc of a life. It’s interesting also that you wrote a book so centred around pain, the limits of the body, and the dissonance between body and mind, while you were so sick yourself. Had you planned to write it before getting ill?

PS: Oh, wow, Jesus Christ. You are absolutely right about the arc, but I’d never noticed that before. Your saying this actually helps to provide another answer to your earlier question about the role of the critic, which is sometimes to interpret art on behalf of the artist (if you’ll allow me to refer to the book as ‘art’ for a moment).

As far as the timing is concerned, spookily I wrote the proposal, then had it shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize in February 2020, so not only was I not aware that I was about to fall ill, then become chronically ill, I had no real idea we were about to enter the pandemic. Logically, there’s no way that the experience of that illness failed to influence the writing of the text, and now you’ve mentioned the shape of it and the relationship that shape has with the shape of life in general, I wonder whether this was some sort of subconscious decision – certainly, I’ve never been in a situation before where I’d been ill enough that I feared, however briefly, that I might die, and there’s a lot of death towards the end of the book. Interestingly, my partner read it and said that the final section made me sound religious, which I’m not. These are questions for my subconscious and not my conscious mind, I guess!

“Increasingly, the merging of high and low culture is seen as a fairly standard way to write as a critic; it’s always been my preferred mode” – Philippa Snow

HC: Your writing is often very funny, and you have a knack for seeing the humour or wit in something; in the book, you make a great case for Marina Abramović’s sense of humour, and Harmony Korine’s too. What do you think the importance is of ‘seeing the funny side’?

PS: Oh God, it is so, so important to me! I need people to understand that when I am, for instance, writing about Logan Paul’s YouTube in the context of Andre Breton’s definition of surrealism or whatever, I am absolutely making fun of myself as much as I am making a point. I think it’s possible to do both things simultaneously: to apply serious analysis to an unserious thing and in doing so make a salient point, and also to recognise the inherent preposterousness of applying that kind of seriousness to some of the dumbest things on earth. The idea that I take myself too seriously might be one of the worst things a person could take away from my writing, to be honest; I find it hard to connect with writers who don’t have at least a little touch of humour – not zaniness, not silliness, but some deadpan sense of the absurd – in their work.

Patricia Lockwood, for example, is one of the only critics where I will run, not walk, to see whatever she’s just published at the LRB. I think what she does is magic, really – I aspire to that weightless blend of being hilarious and having such impossibly sharp and delicate powers of observation.

HC: In the book, you quote the artist Nina Arsenault: ‘Everybody’s lives are mythic, everybody’s lives are big. It’s a lie of TV, capitalism, propaganda, that our lives are casual … ’ I think this also, in a way, describes your approach – that you assume there’s intelligence and meaning in most things and set out to find it.

PS: I think almost everything – and almost every life, as Arsenault suggests – has the potential to yield something touching, or funny, or revealing in the documentation and analysis of it that helps to explain something about the way we live. I’m struggling to elucidate this without sounding like someone from mental health TikTok or a motivational meme page, perhaps because I’m deeply uncomfortable with being earnest. But then fuck it, also – what exactly is wrong with being earnest? I think this might actually be a deeply earnest book, underneath the dry jokes and the art historical analysis and the Logan Paul content and whatever else. I’ve made my peace with that.

Which As You Know Means Violence by Philippa Snow is out now.