Following Jean-Luc Godard’s death, we look back on five of the French-Swiss director’s must-see films; from Breathless to Band of Outsiders

Where do you begin with Jean-Luc Godard? Perhaps with the fact that he is almost universally acknowledged for being responsible for the most visually influential work in the history of cinema. As a founding member of La Nouvelle Vague (the French New Wave), Godard was the intellectual enfant terrible of cinema; an inventor, provocateur, disruptor, deep thinker, always moving fast, over productive and experimental to the extreme, delivering a never-seen-before aesthetic.

His cinematic collaborations with Anna Karina are still points of reference within the film and fashion industries (Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino have referenced Godard’s work, among others, along with brands including Dior, Chanel and Agnès B). His spontaneous and sometimes chaotically organic approach was widely admired but annoyed others (Ingmar Bergman was starkly against Godard's “self-obsessed” cinema, saying it was “boring, affected and dull”). Godard didn’t influence the culture, he became the culture. In light of the maestro’s recent passing, we look back at five of his greatest films.

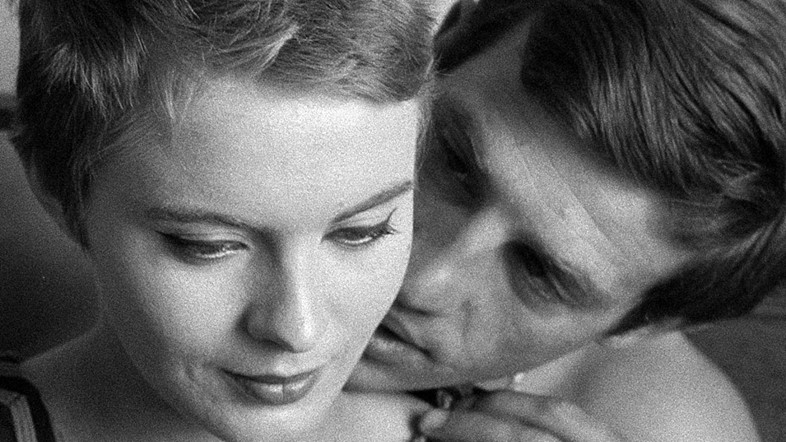

À bout de souffle / Breathless, 1960

Godard’s first feature-length film follows a pixie-faced Jean Seberg and criminal Jean-Paul Belmondo on their journey to self-fulfillment. One wants to become a successful writer, the other wants to hide in Rome. With his impulsive gangster attitude, Belmondo’s look became the most coveted in men’s fashion during the 1960s. Equally, Seberg’s slim trousers and white shirt paired with ballet flats waved goodbye to Dior’s New Look and gave us instead the garconne; a new feminine ideal. The pair looked remarkably cool together strolling up and down the Champs-Elysées, complete with American accents and boyish cockiness.

Pierrot le Fou / Pierrot the Fool, 1965

With Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo as a murdering couple on the run, Godard created some of the most vibrant compositions: blues, reds, yellows and greens dominate the images. Beneath the startling editing lies a philosophical element that provides the visual framework of the movie. When Marianne and Ferdinand reach the last leg of their escape, they painfully emerge out of the ocean, giving birth to a new beginning. The island Porquerolles turns into the third person. Lonely and self-destructive, violence takes over their lives. Pierre’s blue-painted face becomes one with the sky and the sea. In the end, the Mediterranean devours its figures in a fantastic but tragic manner. “We found it. – What? – Eternity … it is the ocean and the sun.”

Le Mépris / Contempt, 1963

In awe of architecture and awareness of space, Le Mépris is a film about making a film and all the strains that go with it. At times evoking the look of a Bauhaus poster, the film was partly shot in Casa Malaparte in Capri, one of the most renowned examples of modern Italian architecture. None other than Fritz Lang stars (and speaks!) in this story, admiring the gods while profane marriage issues take place. Brigitte Bardot’s headband, black eyeliner, blonde hair and striped top could have been illustrated by Malika Favre, so graphic is almost every aspect of the film. At the insistence of the producers, Godard had to include Bardot’s nudity for the film to become a more commercial success in the States. It is spectacularly done, in the most tame yet cynical manner, delivering us the lines of her silhouette rather than her actual body.

Bande à part / Band of Outsiders, 1964

The film which Tarantino named his production company after, is true to Godard’s motto: “All you need for a film is a gun and a girl.” And Paris. Godard's most playful and charming film is perhaps his most accessible one. Our gangster triangle does everything but the heist they’re planning to do. They hang out in cafes, go to the Louvre, spend the night together, dance, drive around in their convertible car … accompanied by the dreamy sounds of Michel Legrand. Tarantino said of Bande à part that it was the one film that showed him that you could have fun as a filmmaker and play with the medium, thus recreating the Godardian narrative: “A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

Vivre sa vie / My Life to Live, 1962

Probably Godard’s most sombre film, Vivre sa vie tells the story of aspiring actress Nana who ends up working as a prostitute and gets meddled into dangerous business. In typical New Wave fashion, Godard gives us an instruction manual in the form of an actual typographic list and off-voice narrator, on how to be a full-time prostitute and what you should consider. Nana’s helplessness cannot be masked by her pathetic attempts at being shrewd or slightly in charge of her own situation. Just like she gives away her body, it is not her life anymore. Her black bob hairstyle appears as a homage in Le Mépris, when Bardot pops it on in a moment of self-reflection.