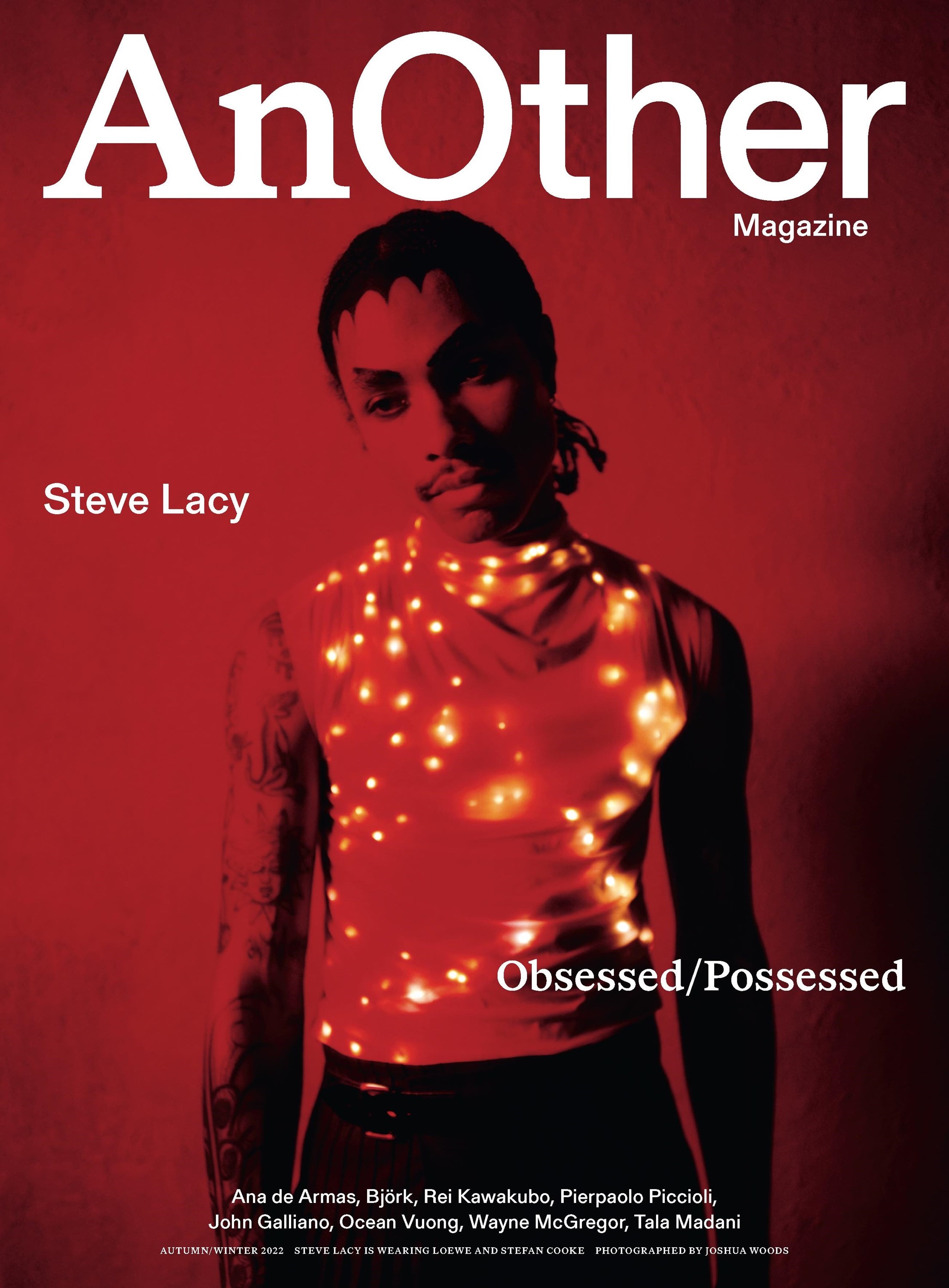

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine:

In June 2020 Steve Lacy’s life changed. He was driving through a canyon in the mountains near his home in Los Angeles, California, on a road that had space for just one vehicle, when a car hit him head-on.

“I remember a black flash,” he recalls. “I thought I’d died. It scared the shit out of me.” After several moments he opened his eyes and looked down at his body to check he was OK. “Still in this bitch,” he remembers thinking with relief. He quickly got out of his car, worrying that it might explode, and escaped, miraculously unscathed but for a few cuts on his hands.

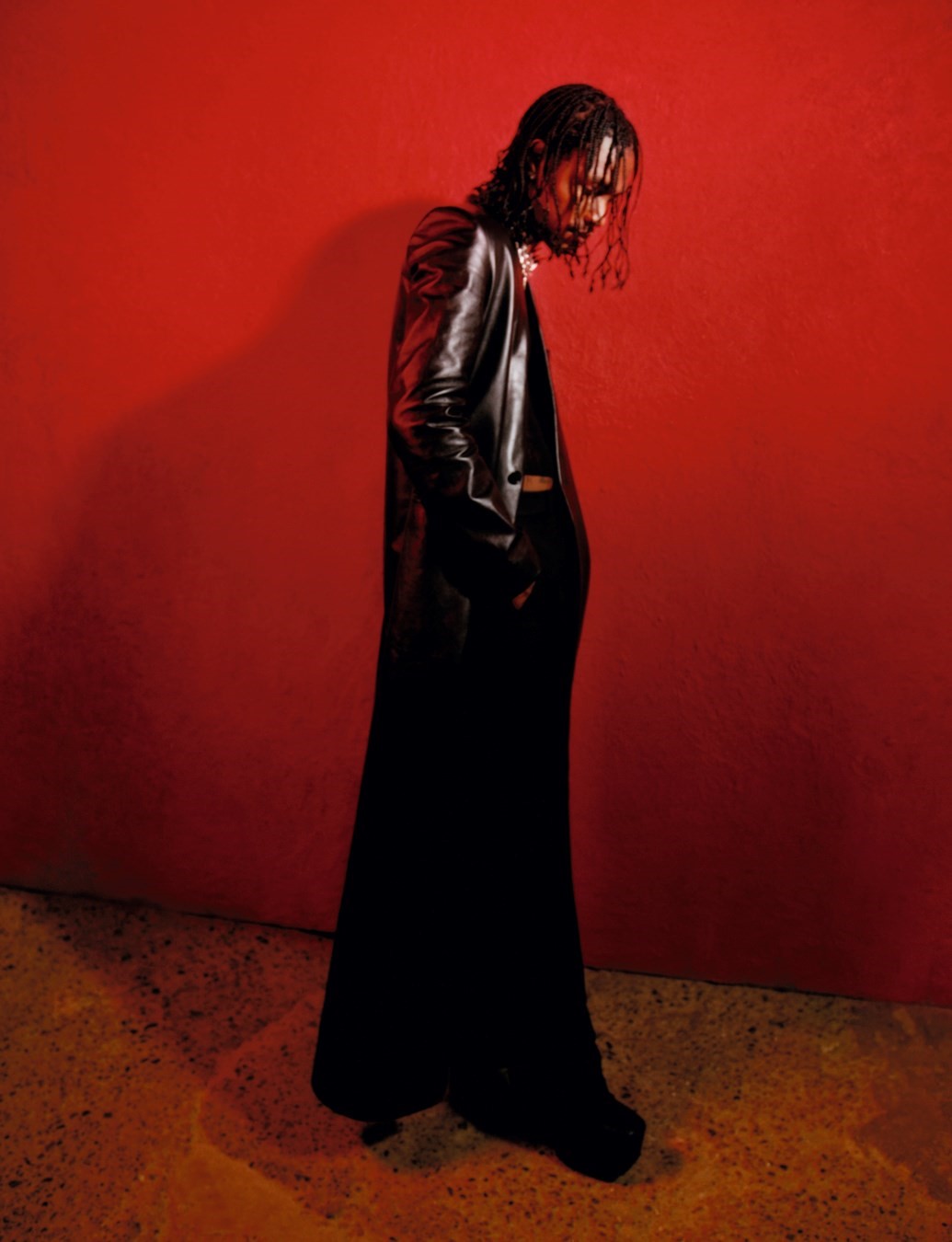

This event had a profound impact on Lacy, who is sitting across from me in a restaurant in east London, dressed in all-black Balenciaga. He shares the story only after I ask him what motivates him, what gets him out of bed in the morning. After pausing for a good 30 seconds he responds simply with one word: “Death.”

“Death,” he repeats. He has already mentioned, early on, that he has a “sarcastic, satirical” sense of humour, so it’s hard to tell if he’s joking or not. That seems to be true – but here he’s sombre, reflective. “The realisation that death defines the meaning of your life,” he continues. “I feel like that near-death experience shifted everything in a way. I felt lighter afterwards. It made me look at my life. Like, what matters? What am I going to put my energy into?” He tails off.

An encounter with death does things to the human psyche – it may paralyse and perplex, freeze or free. For Lacy, his brought him back to his music, to consider his legacy. It’s startling to hear a 24-year-old talk so seriously about that. “I look at my life as a museum, like experiences that I collect,” he says. “How I touch people’s lives, the energy that I put out into this world. What will I do to keep that flowing? I think music is an opportunity to tell a story and create a thread for someone else to continue, even when you’re gone. That’s what keeps me going. That’s what keeps it fun, because this won’t be for ever.”

Steve Lacy was born in 1998, in southern Los Angeles County, his mother is African American and his father was Filipino. He had a broadly middle-class upbringing, attending a private school during his early years, and shielded from the potentially rougher parts of Compton by his mother, who encouraged him and his three sisters to stay indoors. Describing the city as a “‘hood suburb”, Lacy acknowledges that there is some truth to the public perception of his hometown – but says it’s only half the story. “It’s not the entirety of the city. My family is there – it gives a depth to my persona and even my brain and how I operate. It’s not too bad.”

Lacy’s father was absent for much of his childhood and died when he was ten. A knock-on effect was that Lacy lost that connection with his Filipino heritage. “I had no access to that side, that part of myself, after my dad passed,” he says. “And it just left me with this curiosity, too. I don’t really have time to figure it out at the moment, but I want to. I still eat the food though, I still go to the restaurants we used to eat at. I love adobo and pork sinigang – he used to make that.”

Around the time he lost his father, Lacy discovered what would become his lifelong obsession: guitar. “I was playing Guitar Hero from about then. I was obsessed with the instrument and then I started playing.” Lacy says he was fairly average academically – “I was all right in school. I wasn’t super-studious, I just kind of got by. I didn’t really agree with the curriculum, ever” – and he describes himself at that age as socially “a floater” who had a couple of friends but never a clique of his own. That changed in his freshman year of high school, when he joined the school jazz band: through that he not only found something he excelled at, but a group of friends that would alter the course of his life. Those friends were the Internet, the neo-soul band formed in 2011 by two members of Odd Future (the music collective that counts Tyler, the Creator and Frank Ocean among its members): Syd (formerly known as Syd tha Kyd) and Matt Martians, when they were 19 and 23 respectively. The Internet gained popularity for their unique, off- and upbeat brand of R&B soul and by the time Lacy joined them in 2013, they had two studio albums under their belt and had begun work on their third.

Lacy’s introduction came by way of Jameel Bruner, a senior at his school and fellow member of its jazz band who was keyboardist for the Internet at the time. He and Lacy had become close and Bruner began to invite him to the studio. “I was really quiet, so I would kind of just do my part, just play,” he remembers. Before long though, he was a fully fledged member of the band – they performed at the second Camp Flog Gnaw Carnival, the music festival curated by Tyler, the Creator, formerly known as the OFWGKTA Carnival, “and Jameel was like, ‘Yeah, you’re the next recruit.’ Once I got recruited, I started opening up a bit more. We’re like family now.”

Lacy was 16 at this point, making music with the Internet and performing with them whenever he could – his age prevented him from playing at certain venues, while his school commitments held him back from other gigs. “I wasn’t like some celebrity kid,” he says. “Nobody on campus really knew. I wasn’t flashy about it. Plus, the Internet wasn’t a high-school band. We had an older crowd at the time. Now we have everyone, but at the time the kids in my school had no idea. I mean, the super Odd Future fans knew, it was a couple of kids here and there. It was pretty regular – I would play gigs and then just go back to school.” In 2015, the Internet released their third studio album, Ego Death, which was nominated at the 2016 Grammy Awards for Best Urban Contemporary Album. “It’s a treasure,” Lacy says of the record. “It brought me here. I’m super-proud of it. I had no idea that any of this would happen to me. I was just jamming, you know?”

“Music is an opportunity to create a thread for someone else to continue” – Steve Lacy

Lacy attended the ceremony at the Staples Centre (as it was known then) in Los Angeles with his bandmates; Kendrick Lamar took home five awards, Taylor Swift took three, and the Internet sadly lost out to chart-topping artist the Weeknd. And yet, in spite of all the excitement of that evening, Lacy went to school as normal the next day, again resolutely casual about the whole experience. “It was fine,” he says. “Not that many people knew. It was really calm.” It’s perhaps a cliché but Lacy is refreshingly normal. He wears his fame and success lightly, especially given that he has effectively been working in and around show business his entire adult life. He may have the fact that he stayed at school, where people didn’t treat him differently, to thank for that. “It was very grounding,” he says. “I liked it. I felt like Hannah Montana.”

The day after Lacy graduated, he flew to Bonnaroo, the music festival held in Manchester, Tennessee, and from there to a festival in Japan, and on. In 2017, Lacy released his debut solo project – a series of songs titled, directly enough, Steve Lacy’s Demo. Two years later, he launched his debut album, Apollo XXI. Since joining the Internet, he has also collaborated with a host of artists, including Solange, Tyler, the Creator, Blood Orange, Kendrick Lamar, J Cole, Kali Uchis and Vampire Weekend, an exhausting but not exhaustive list of the major talent he has worked with.

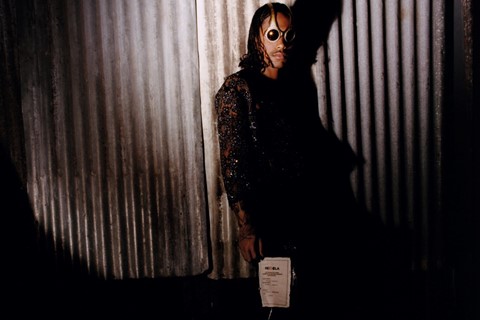

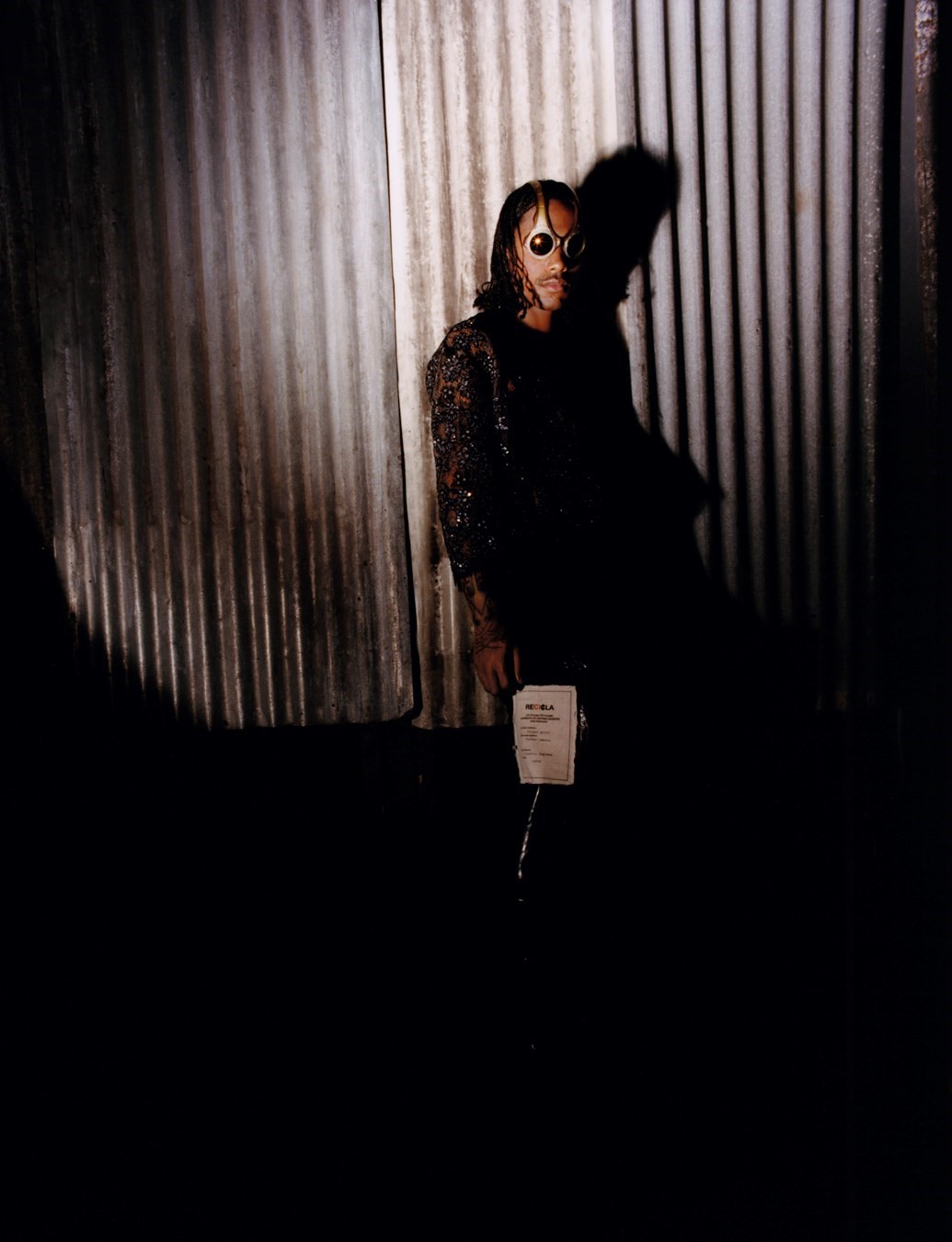

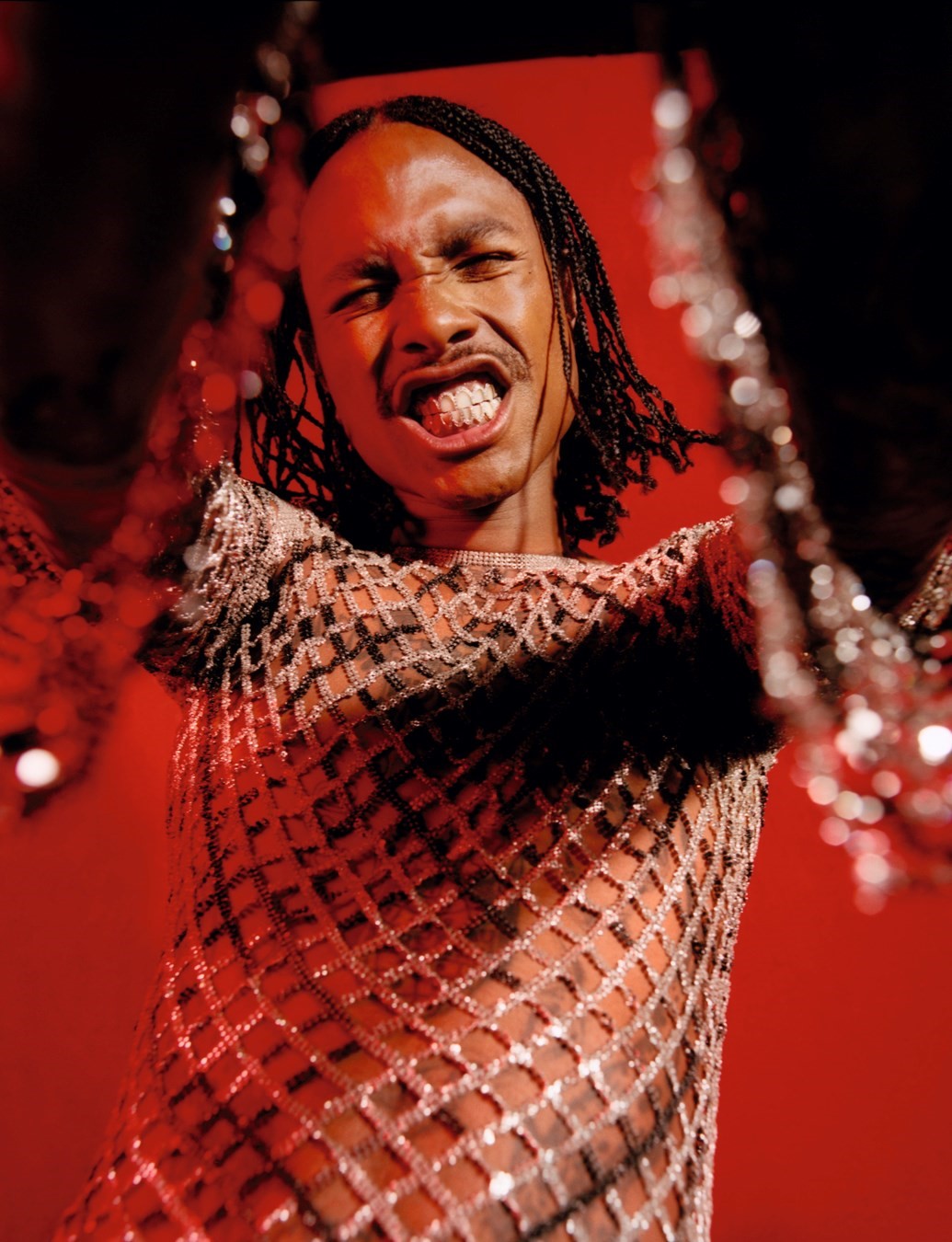

The first time I saw Lacy perform was in November 2019, at the O2 Forum Kentish Town in north London, on tour for that album’s release. Wearing an iridescent silver vest, black leather trousers and sunglasses, he dominated the stage without the aid of dancers or elaborate set design. For many tracks it was just him and his guitar. Flying around as though he had wings, Lacy had an energy that was electrifying, jolting the 2,300-strong crowd that bounced around with an enthusiasm that mirrored his own.

The next time I see Lacy it’s the other side of a pandemic and he is altogether more sedate. Having moved into his first home, gone through a break-up, done a lot of processing and begun work on his new album, Gemini Rights, during that time he seems in a good place. He’s over from Los Angeles, where he lives with his American bulldog, Eve, and is gearing up for the album’s release. He’s relaxed, smiling. “I’ve got a more fluid relationship to change now and that makes me feel calm,” he says when I ask what precipitated this feeling of wellbeing and contentment.

Gemini Rights is his second studio album, the result of two years’ work and a ten-track edit of more than 300 songs. “I felt like the studio was a gym, you know? I was getting my reps in,” he says. “I made a bunch of bullshit to get to this. I meet new musicians and they’re like, ‘What do you do?’ I’m like, bro, you gotta make trash. You can’t skip the trash. You can’t just, like, conceptualise a good idea. You gotta make some bullshit. I made a lot of bullshit to get to this. I got some fun demos, though. I got a demo about coming in someone’s hair. I think I’ll leak it on TikTok.” He plays a bit of this song later and laughs.

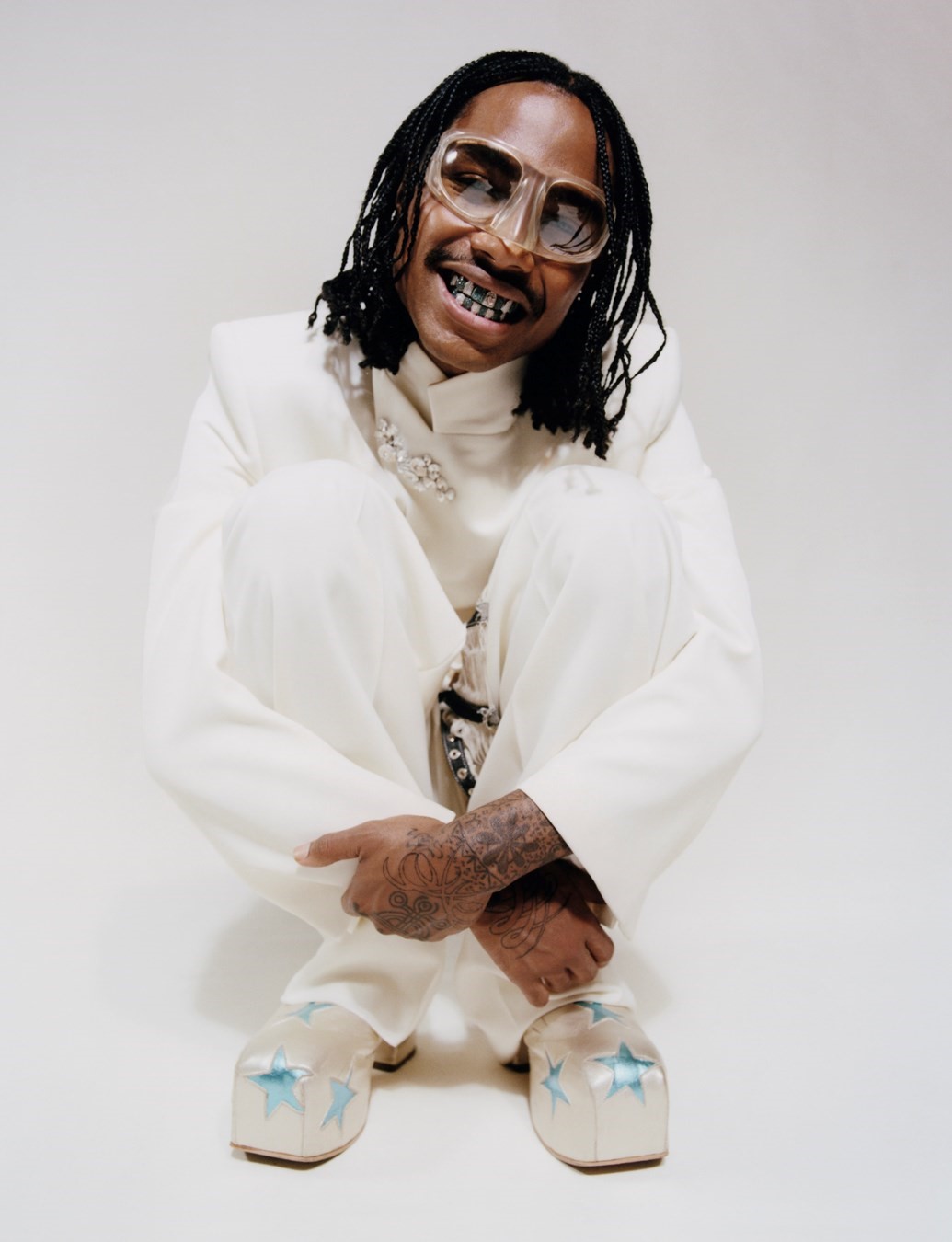

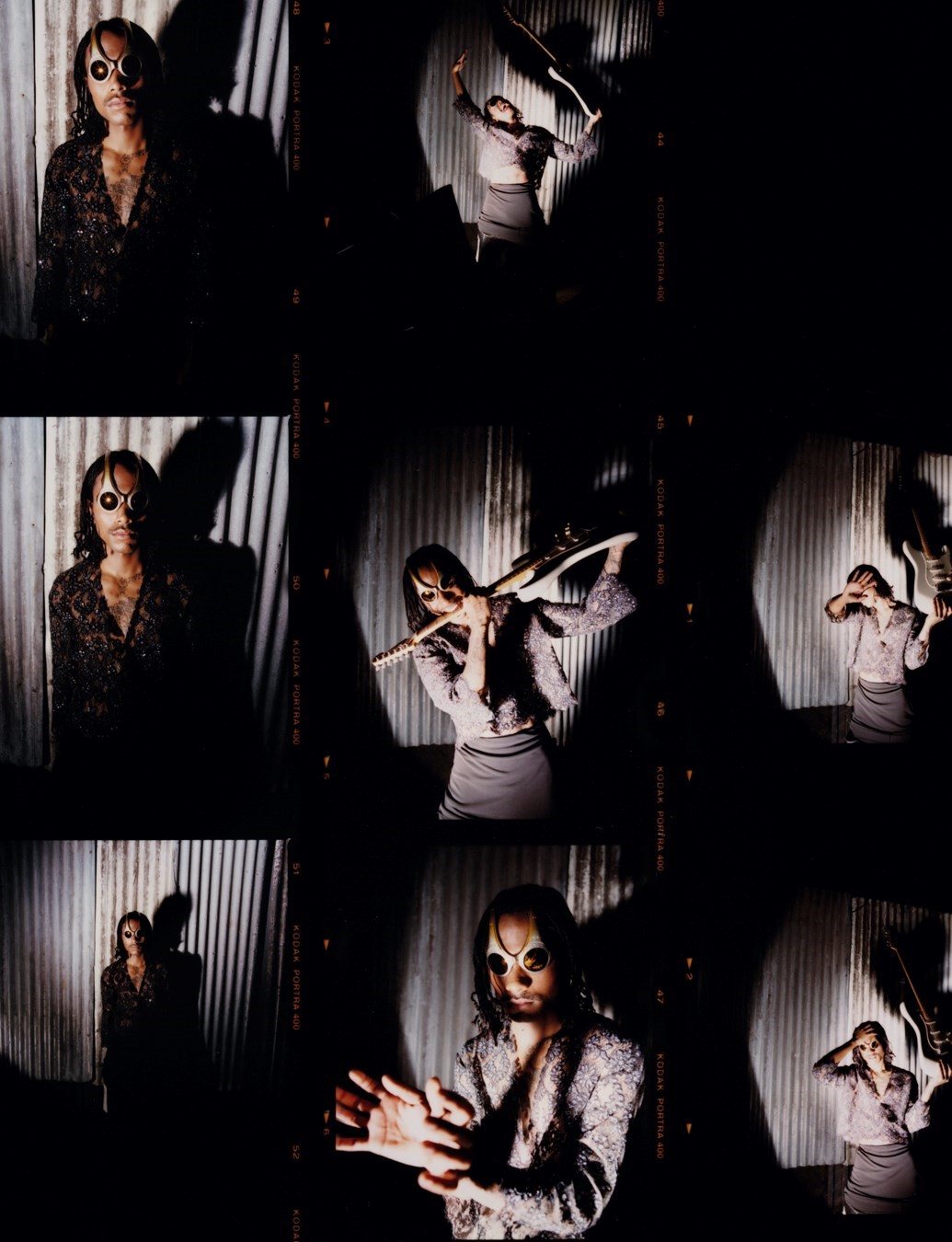

Lacy feels that this new album represents him better than any other music he has released to date – it captures not only his personality and the nuances of the way he speaks, but the way he jokes too. We meet his sense of humour early on, even if we don’t realise at the outset: it’s there in the title Gemini Rights – a sardonic take on the notion of gay rights, Lacy tells me.

“I was just in a bar with my homegirls in New York and I heard someone say ‘gay rights’ and then I was like, ‘Gemini rights’,” he says of the story behind the album’s name. “I kept saying it as a joke. Then I was like, ‘What if that’s the album?’ I had the name before I even had the songs written, and then as I started to write, it kind of created a theme for me to be this type of character.” That character is one of the zodiac’s most divisive, often seen as two-faced and duplicitous, fickle and fake. “It’s always, ‘Oh, you’re a Gemini,’ like, in disgust,” he says. That said, Lacy doesn’t place too much stock in astrology. “I don’t like to generalise too much. I feel like there’s so many components to what makes a person who they are.”

“You gotta make trash. You can’t skip the trash. You can’t just conceptualise a good idea” – Steve Lacy

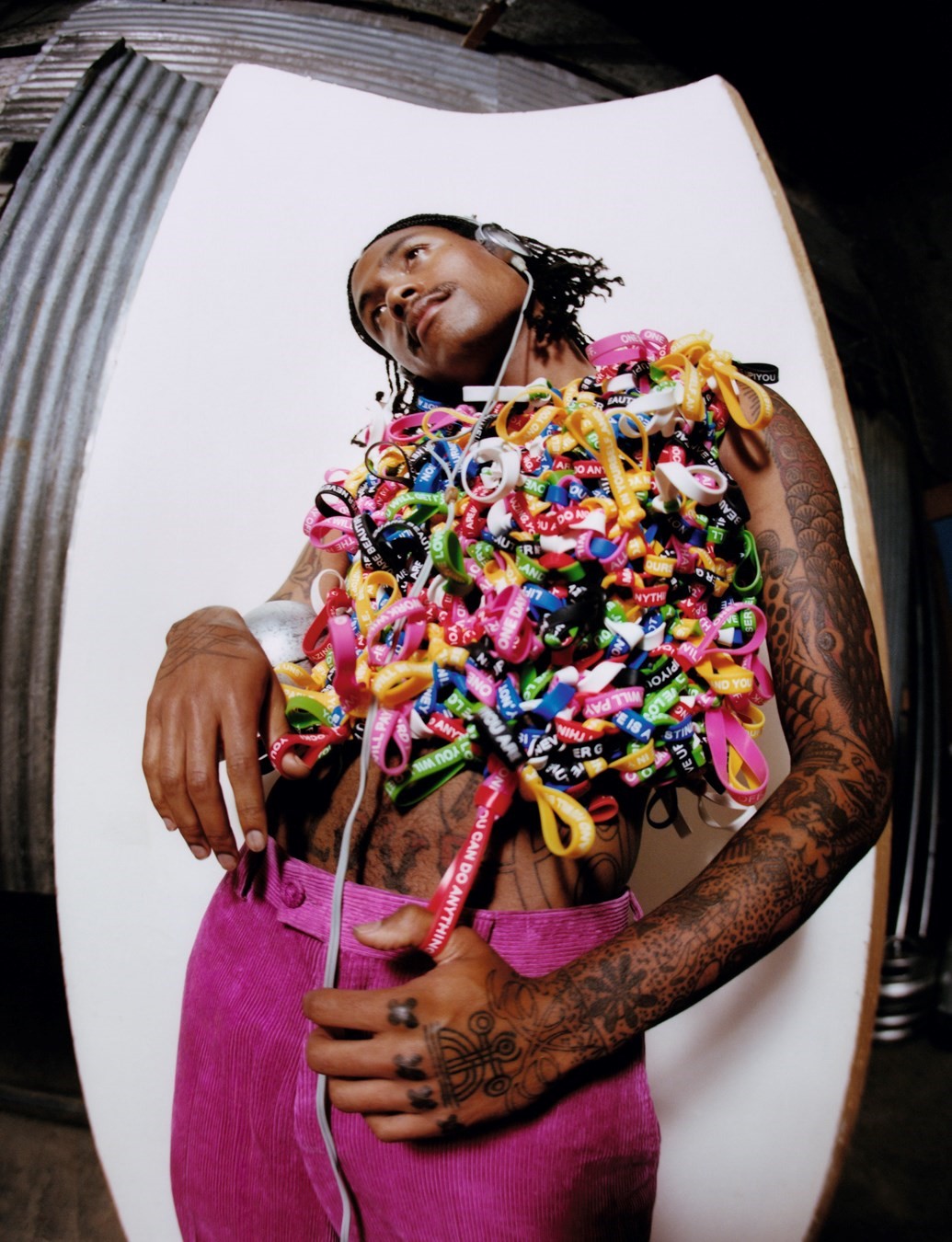

The idea of duality – the two faces of a Gemini – is certainly applicable to Lacy’s persona, or maybe personae. He’s both streetwise and a self-proclaimed geek; he seems sweet, even innocent, but as might be obvious given his sexually charged lyrics, he’s provocative too. He’s an introvert who admits to finding people scary, who says he feels safest around a small group of people he knows, yet commands crowds of thousands of fans singlehandedly with a magnetic stage presence. “After shows I ball up in my room and don’t say a word for a couple of hours,” he says of any apparent paradox. “I just have to feel safe. I have to find my corner.”

Another paradox: a musician who enjoys quiet. “I love silence,” Lacy says. “Being by myself and not talking. I was having a conversation with my therapist about having moments where I feel lonely. And she told me that’s a signal that I need to be alone. I was like, ‘Oh, wow.’ It helped.”

Lacy has been spending a lot of time on his own since breaking up with his boyfriend in August 2021, which brings us to Gemini Rights. “It’s a fucking break-up album,” he says, laughing. “I was just in the studio, grinding and writing through all the anger, all the sadness.” Despite the undercurrent of heartbreak, the album is positive and philosophical about the relationship in question. “Don’t regret the choice I chose but do regret the mess I made,” he sings on the track Mercury. The album is optimistic towards the end with Sunshine, a duet with the New Jersey-born soul singer Fousheé, whose fame spiked in 2021 thanks to TikTok. The pair joke about still having sex with their exes.

Gemini Rights is different from anything Lacy has released before. He says he hit a wall doing everything on his own and so brought people in this time, making a concerted effort to be more open to other people’s input. The result is a record that has been produced and polished, in contrast to his rougher DIY demos, most of which were recorded on an iPhone. Lacy also admits he has felt pressure as an artist coming of age in the public eye, though says he’s grateful for it – and for what he calls his “small spurts of success”. “This is the first time I consciously said I was an artist, because before this album I was just getting some shit off real quick. I didn’t think too hard about it. I didn’t think I was an artist. I thought I was just a guitar player. I thought I was just a producer, a vessel to help other people – and I still feel that way but I feel comfortable calling myself an artist now too.”

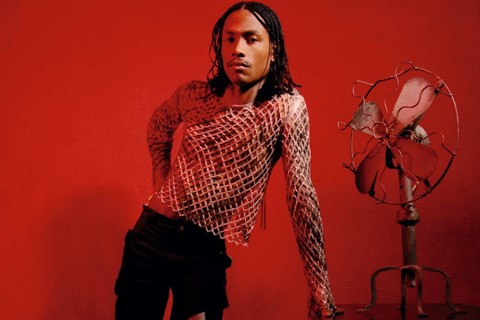

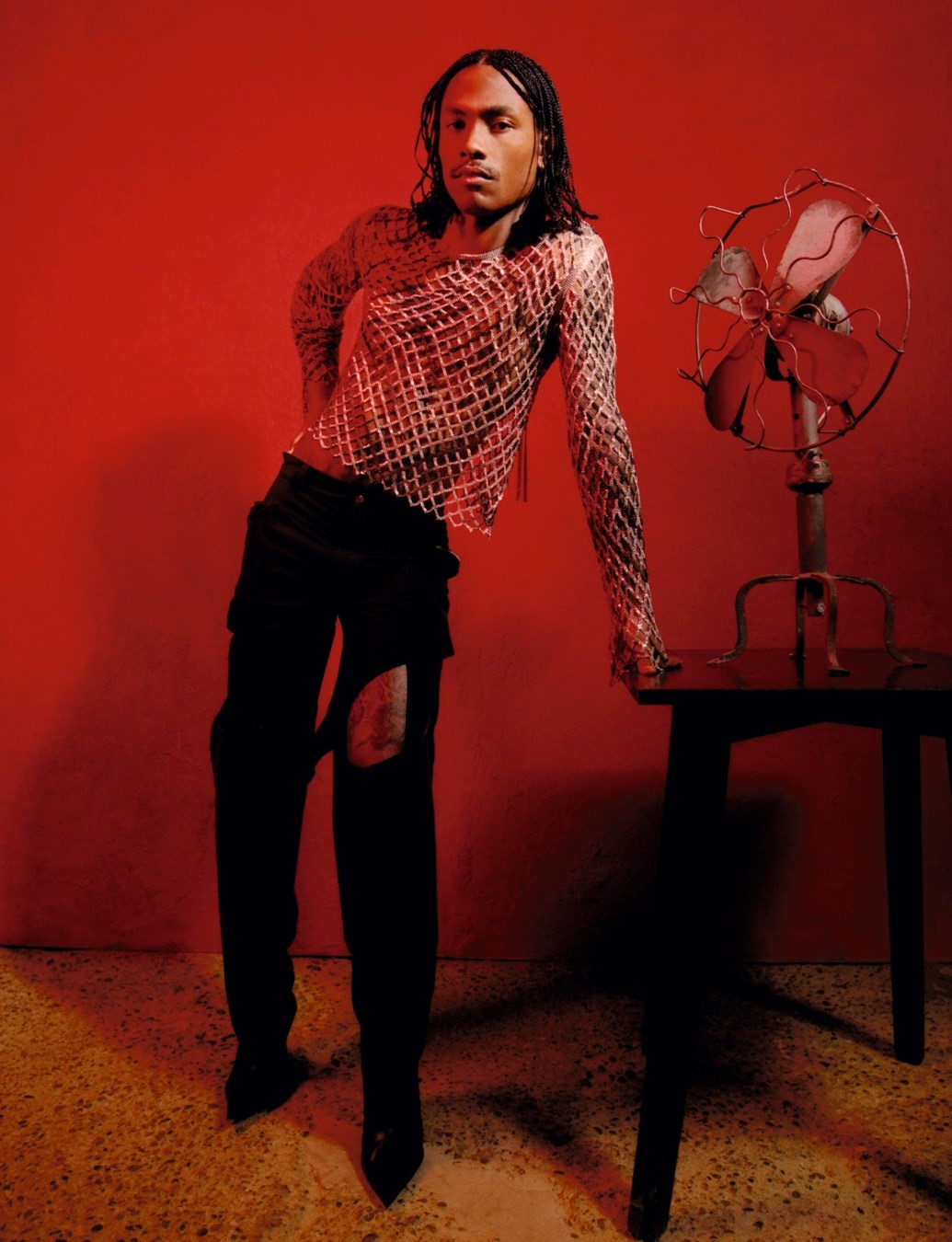

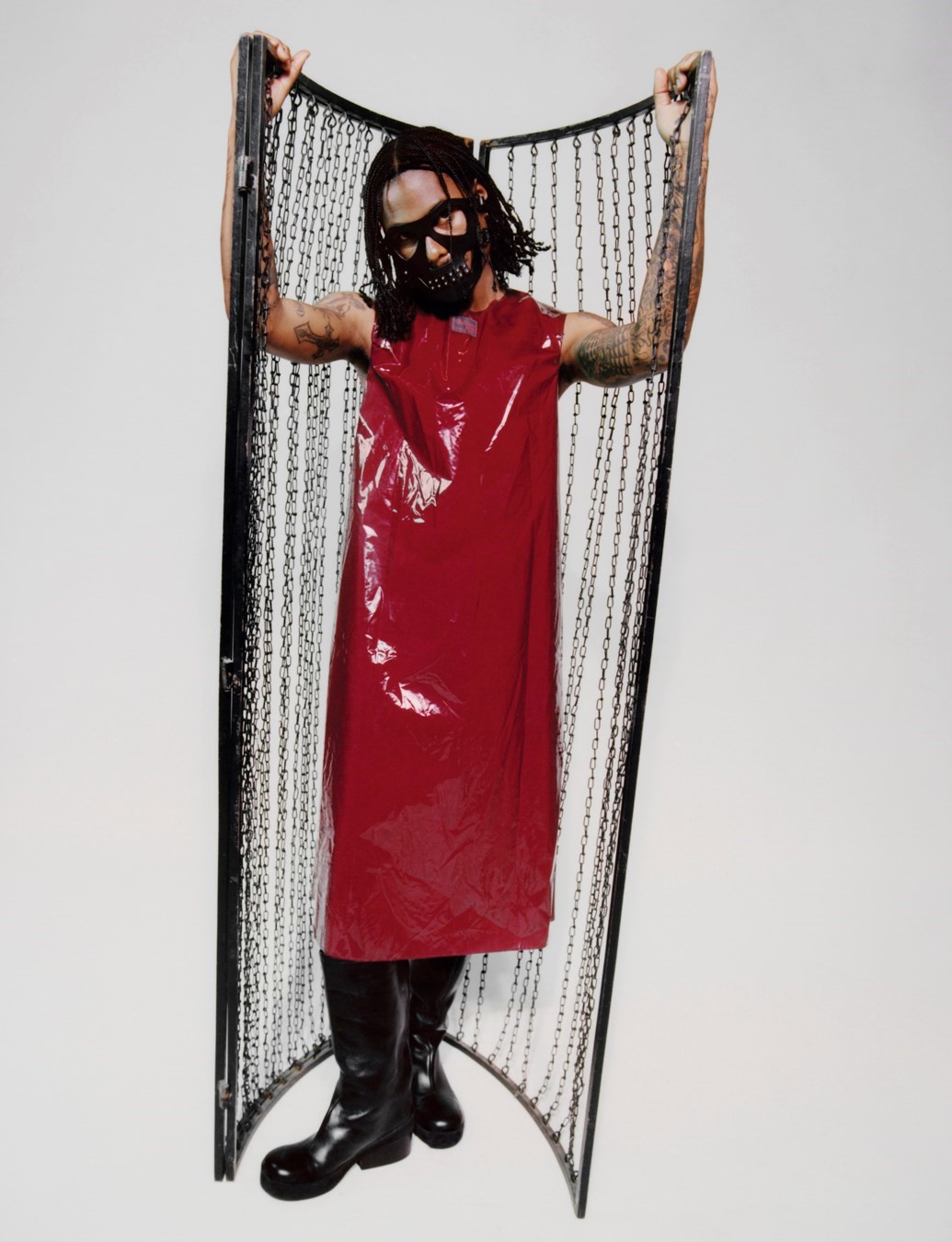

Lacy’s relationship with gender and sexuality – and the interplay between his own masculinity and femininity – is notable. Lacy himself identifies as bisexual – he came out on Tumblr in 2017, inspiring much analysis, both in the comments on his page and in online publications. But he hasn’t let this define him, saying in 2019 that he doesn’t like “to make it a big deal”. He is not only attracted to both genders, but his appearance slips and slides between conventions of masc and femme, between football jersey and leathers and dresses, skirts, sparkly bags and sequined boots. He has a sometimes-private Instagram account called @fitvomit where he chronicles these looks but this album feels, in some senses, like a rejection of both men and masculinity. “Lookin’ for a bitch ‘cause I’m over boys,” he sings on one track, while others are sung in a falsetto where he mimics a female vocalist so successfully that friend and collaborator Tyler, the Creator was convinced it was a woman singing.

“I wanted to sound like a girl because I love women’s voices,” Lacy says. “I don’t listen to that many men. There’s something ... ” he pauses, choosing his words carefully, “endearing about women’s voices. I believe them. I grew up surrounded by women so maybe they make me feel safe and calm. And I think they’re sexy, I don’t know. So I wanted to sound like a girl on this album. [Tyler was listening to it] and was like, ‘Who’s that singing?’ and I was like, ‘Me!’ and he was like, ‘Oh shit.’” He laughs. “Mission accomplished.”

Lacy connects women and safety. The security that his mother and sisters bring him extends to his position in the public eye, which can of course be testing. “They are protective of me, but they trust me enough not to take it too crazy,” he says. “I’m with them a lot. I try to do things and be around people that make me feel normal. And I try to stay out of places where I feel like I have to perform.”

“It’s a fucking break-up album. I was just in the studio, grinding and writing through all the anger, all the sadness” – Steve Lacy

A number of those women in Lacy’s life appear on Gemini Rights: his mother provides backing vocals on the eighth track, Amber; she and Lacy’s sisters all sing on Helmet and Give You the World; and his friend Fousheé features on that aforementioned track, Sunshine. “I used my mom and my sisters on my last album, on the track 4ever,” Lacy says. “It kind of happened on the fly. I was at home making this idea and they were around. So I was like, ‘Hey, you guys want to record this thing I just did?’ But my oldest sister missed out, so I was like, ‘OK, let’s plan another one for this album, everybody has to come.’ So it’s just to put my oldest sister in there, but it worked out perfectly. And I needed that texture on my album. I see music as texture and I just like the texture of women’s voices.”

Lacy talks about the texture of music a lot. He hears beyond melodies and harmonies, perceiving a whole world of sound. When I lightly suggest he’s a music nerd, he agrees and says he’s a “fucking geek”. “I hear the most random things – things no one else pays attention to. Like a vocal effect. There’s this song, Master Teacher by Erykah Badu, and in the second half – I’m about to get really nerdy – she starts belting and her voice goes eight bit, but also it sounds like there’s a knob being twisted. I’m just like, ‘How?!’ There are also different textures and synth stacks on Stereolab songs that I just geek out over. Like I said, I hear music as textures. And I can dissect a song as soon as I hear it.”

More than anything, Lacy just wants to be himself – the music nerd, now “artist” – and to encourage others to do the same. “It’s really basic but it’s so much – the fulfilment that you get from being yourself. The things the world tries to take from you growing up, leave you further and further from yourself. And they show you examples of how to be like someone else. Everyone’s interesting in their own way. Do things how you want to do them. I stand for individuality.”

And what of Lacy’s legacy, then? “My hope is that people make more weird, challenging music,” he says. “That people make more timeless things from Gemini Rights, get out of the algorithm mindset. My hope is to bring the artists back. People are always saying that our attention spans are getting smaller. I don’t believe that – I think the effort to make things that last long is dying. So I hope that people make things that will last, things that are sustainable.”

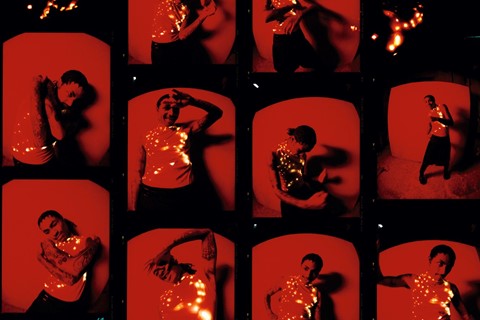

Creative consultant: Ahmed Alramly. Hair: Issac Poleon at CLM using L’ORÉAL PROFESSIONNEL. Make-up: Mata Marielle at CLM using CLARINS. Set design: Patience Harding at New School. Photographic assistants: Andy Broadhurst, Dominic Markes and Abena Appiah. Styling assistants: Bella Kavanagh, Douglas Miller and Mary Hovhannisyan. Set-design assistants: Charlotte Cook and King Owusu. Production: TIAGI. Executive producer: Chantelle-Shakila Tiagi. Producer: Martha Barr. Production runner: Tamara Ohene. Post-production: Ink.

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally now. Buy a copy here.