South London’s cktrl and Jenn Nkiru are two creative souls shaping their narratives through an unapologetically Black lens. Even though the musician and filmmakers work in separate fields, the two friends’ paths frequently cross through their collective experience of elevating their Black identity through art.

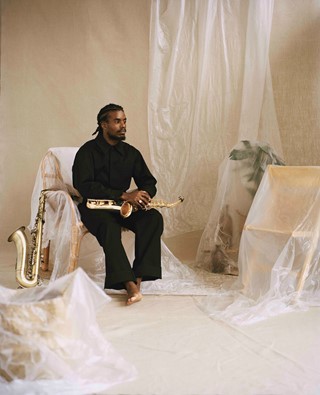

Jenn Nkiru, a self-determined Black woman, enrolled in Howard University, where she would bump heads with Arthur Jafa and Bradford Young. Her catalogue is robust and expansive, spanning from doing filmography for En Vogue and directing the visuals for Beyoncé’s Brown Skin Girl, to being the second unit director for Ricky Saiz’s music video for Jay-Z and Beyoncé’s Apeshit.

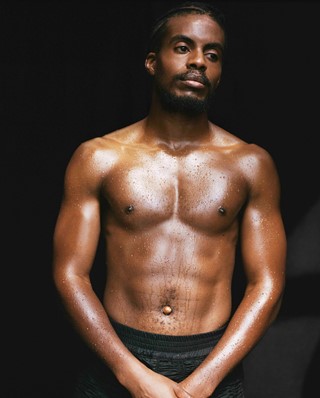

cktrl is also not to be underlooked. Through his exceptional talent, he is redefining the narrative of what the world has come to know as contemporary Black British music. The multi-instrumentalist and producer has fashioned a musical ecosystem that runs on solid values. His latest single, Yield, and new EP of the same name, dropping on October 28, is a cosmic and intense body of work that harks back to the pre-electric era of modal jazz while simultaneously pulling in rudiments from baroque and classical music.

On a bright and sunny Friday evening, Jenn and cktrl jump on Zoom with enthusiastic, sibling-like energy to discuss how south London has influenced their creativity, the erasure and appropriation of Black artistry and how they preserve Black joy in their work.

Jenn Nkiru: I grew up in Peckham and was fortunate enough to be in an environment where many people are from different backgrounds. I wanted to travel as a kid but always felt like living in Peckham. I could travel and see the world on my doorstep. It felt like a microcosm. Regarding my creativity, I have a global perspective in my work based on growing up in an environment where many different places influenced me. My work is globally focused, so much of that nature has found itself in how I create and focus.

cktrl: I grew up in Lewisham, next door to Peckham. When I think of the area and growing up there, we had a solid Jamaican community. Even at school, we had a real community spirit. All the Black kids were together, even though we were in this area where people didn’t like us. I suppose growing up was a kind of resistance. Being in a place where there were people like me, I’ve always had a strong sense of identity in my work. As an artist, our practice might change, evolve and grow. But what drives my practice now is that I know there isn’t any competition. I’ve found my lane. It motivates me because it’s healthy. I can create what I want, how, and when with my practice.

“If there was more collective ownership, we could stop the gentrification and appropriation of Black arts” – cktrl

JN: Having such a clear sense of self and confidence is refreshing, and I relate in that way. I’ve always been in my groove. It’s a healthy place; I’m not someone who’s crippled by comparison. I’m not even really concerned with the tide of where the industry or the culture is going. I’m very much loyal to myself. I’m most faithful to the things that drive me and interest me. When I started, it felt different, but I think the industry has become interested in seeing visions that are outside of what used to be the status quo.

I consider myself an artist first, and when I’m creating music videos, I’m always very conscious about how I contribute to this. What new images am I making? What level of inspiration can I bring about? I’ve had so many different experiences – how do I like to combine all these things? Creating something fresh makes people feel brave, and like they can do their thing.

C: As a creative person, it’s only in the last couple of months that I’ve started to think of being financially literate or more business-minded about what I’m trying to do with my work. I think a lot of the time within the culture, compromises are made for financial gain, and then when white people co-op, it's like, ‘Ah, but I got a cheque.’ I feel like if there was more collective ownership, we could stop the gentrification and appropriation of Black arts.

JN: Black people and their labour have always been deemed free for all. Whether you’re talking about slavery or wages, we’re in 2022 now. When you think about the progress of Black people worldwide, we’ve only come into some semblance, so that’s very hard to jump from generation to generation. The idea of paying someone fair dues or even just seeing that person as an equal doesn’t erase itself so easily over two-three generations – that takes time. As Black people, we must collectively come into a space under this kind of paradigm of capitalism, where we are economically aware and aware of our rights that can help shape things. I’m big on owning everything I make unless I’m making a music video, for example. I try and do my best; for example, when making short films, I make sure I own them.

C: Moving to a broader aspect, I think pigeonholing when it comes to Black artists is racism. It damages Black artists because it stops them from being able to achieve all that they want to or all that is out there for you if you weren’t pigeonholed. For example, if you look at D’Angelo and Angie Stone, as soon as they called their artistry Neo soul, it put a ceiling on it – as soon as they coined it, it limited how far the expression could go, and things can’t evolve.

It’s important for Black artists not to be pigeonholed so they can grow and develop because there are already so many gazes on our work differently, whether that be how we’re responding to make it or how we even exist in the world. Pigeonholing has an even more significant knock-on effect on the community. After all, it sells us the illusion that particular things aren’t Black, so what you see is people won’t even express themselves. It’s so dangerous. Pigeonholing stops that creative flow because how do we get those genres in the beginning anyway?

JN: For any living being, any form of narrowing or pigeonholing is stifling through the narrowing of our expression. It hinders the progression of a particular movement and stifles our ability to be and express ourselves as fully dimensional human beings. There are infinite ways to be Black, and if you pigeonhole what the idea of a musician from a particular background should be, it ends up being a form of erasure because many of these sounds people want to relegate started as Black sounds. If you think about rock and roll, it started really with the blues in the south. One of the first rock and roll guitarists was a Black woman named Sister Rosetta Tharpe, but if you look at rock and roll today, you’d assume it's a white genre.

The same thing with techno – people think it’s a European sound, but no, it was created by Black kids in Detroit – many things that they’re trying to keep us from having roots in Black music. These sounds get co-opted by white artists, and the soul of the music gets stripped of it and then re-fed to you in a way you can’t even recognise. If people don’t know that history, particularly young Black people, it makes them believe the idea that they can only do a certain thing because they’re from a particular background. For me, the idea of pigeonholing is a form of control that has a foundation in racism. It’s a racist idea to think that if you look a certain way and come from a particular background, you shouldn’t be able to do something.

“There are infinite ways to be Black, and if you pigeonhole what the idea of a musician from a particular background should be, it ends up being a form of erasure” – Jenn Nkiru

JN: How I’m visualising Black people is very much attached to how I feel and see Black people on the soul level. I think so much of our identity is obsessed with our external identity, hair, and skin, whereas, as an artist, I’m more concerned with the interior, the interiority of Black people. We, as spirit beings, are human beings. If you obsess around the external facade, I don’t think it gives it its humanity. I’m also concerned with Black people’s humanity, and my work showcases moments of joy, expression, and freedom because it’s my hope for us, and it’s also how I see us when I dream, and it’s also how I see us in everyday life.

C: How I capture Black joy in my artistry is guided by the spirit of the thing. Like when it comes to the feeling that I put into my music, my experience, and that’s what resonates because sometimes my music is free of lyrics. It enables you to put your own experience forward. I feel that’s where the beauty is, in terms of people being able to heal their spirit through what I’m putting there. It’s like medicine.

Yield, the new EP by cktrl, is out on October 28.