Starlet, teen bride, ward of Los Angeles county, bombshell, divorcee, nude pin-up, would-be dramatic actress, FBI surveillance target, movie star, addict, platinum blonde, sex symbol, introvert, girl in a white halter-neck dress enjoying the breeze from a subway grating in the steam heat of a New York summer, acting student, avid reader, sequin-clad goddess breathlessly wishing the president happy birthday, death by misadventure, fantasy, orphan, cautionary tale, possible suicide, potential homicide; Marilyn Monroe is one of the most photographed and mythologised figures of the 20th century.

A melange of fact, folklore, and falsehood, the story of Monroe’s life has transcended the specifics and become apocryphal as her biography undergoes constant reevaluation and retelling. History evolves into legend, legend evolves into myth. What remains is a grand American narrative; more metaphor than flesh and blood.

In her acclaimed novel Blonde (1999), celebrated American author Joyce Carol Oates managed the feat of reclaiming Norma Jeane Baker from the realm of mythological archetype while preserving the ambiguity that clings to her cosmically famous alter-ego, Marilyn Monroe. Told through a medley of perspectives – from Norma’s interior voice, a plurality of people who enter her life, FBI reports and scraps of the actress’s poetry – Blonde succeeds in bringing Monroe viscerally alive. Distilling what Oates has described as the “poetic truth” of Monroe’s life, the novel retains the complexities and incongruities she embodied as a shivering, lost soul, grappling with her status as a “sex symbol” in the brutal scrutiny of the public gaze, a fiercely intelligent actor with a unique genius and luminosity, and all the other myriad manifestations of her deeply fragmented psyche and persona.

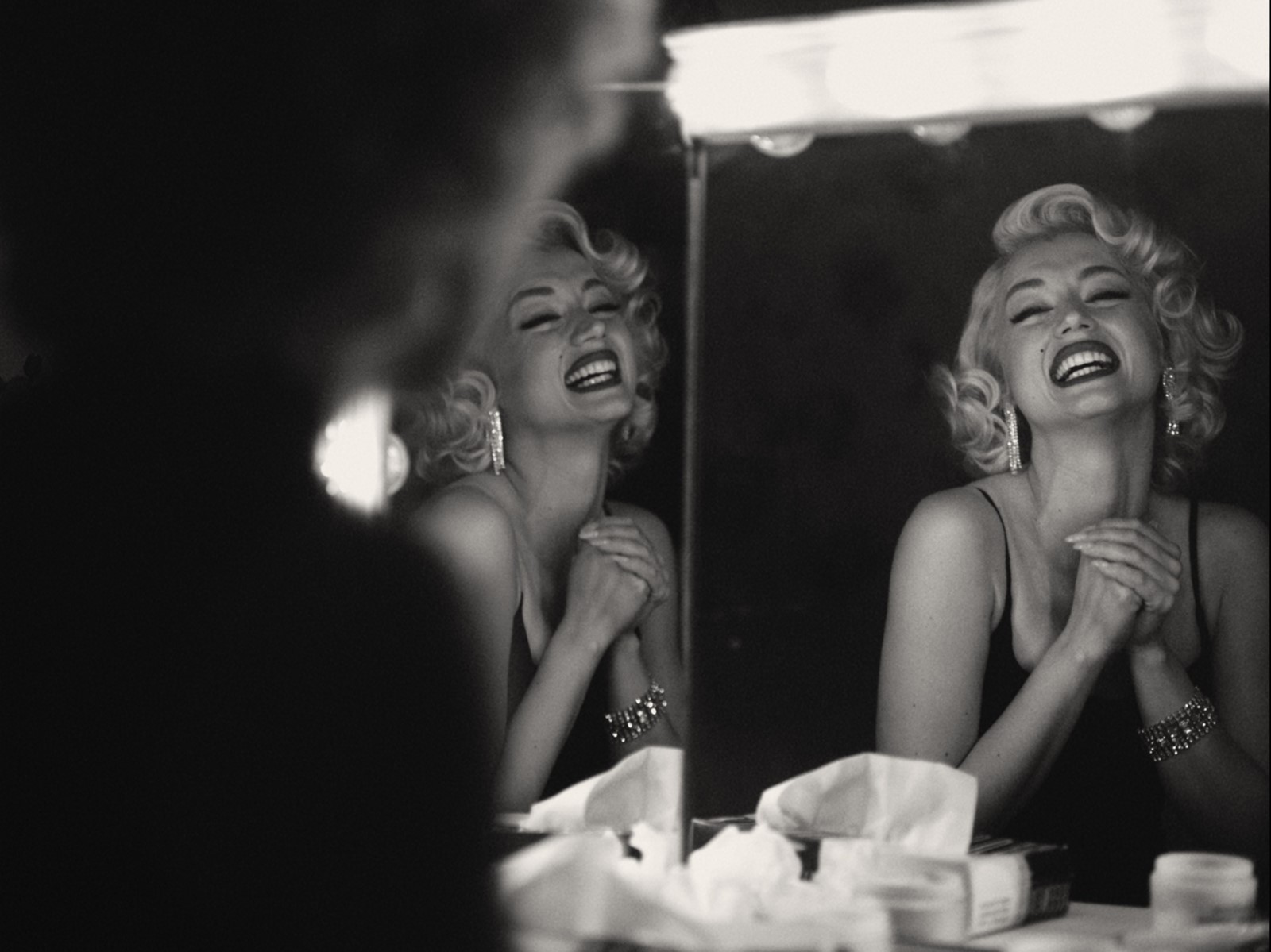

The much-anticipated upcoming film adaptation of Oates’ epic, haunting novel is written and directed by Andrew Dominik and stars AnOther Magazine cover star Ana de Armas as Monroe and Adrian Brody as her third husband, playwright Arthur Miller. In the wake of the movie’s rapturous reception at Venice Film Festival (where it reportedly received a 14-minute standing ovation), we talked to the famed American novelist about Blonde.

In a conversation over Zoom, Oates spoke about Ana de Armas’ “spellbinding” performance, how a photograph of teenage Norma Jeane Baker won her heart, and why this adaptation of one of her seminal works happens to be particularly timely.

Emily Dinsdale: As a reader, it’s nerve-wracking to see one of my most beloved novels being adapted for the screen. As the writer of the book, what was that process like for you?

Joyce Carol Oates: The director Andrew Dominik sent me his adaptation many years ago, so I read that [and] I was quite impressed with it, it was a thoughtful screenplay. I got to know him a little bit better, I saw other work of his and he’s really an artist. This is his vision of the novel, which he sees as a drama – the tragedy of Norma Jeane Baker creating this other persona, Marilyn Monroe, who is her saviour, in a sense, but then being overcome and destroyed by that image.

ED: Do you feel that Ana de Armas really embodies Norma Jeane and Marilyn?

JCO: Ana de Armas’ performance is quite spellbinding, I think she is remarkable. She has evidently spent a lot of time working on the role. She read the novel and she probably talked about it endlessly with Andrew Dominik, and I’m sure she saw a lot of Marilyn Monroe movies. You can get to know somebody, seeing their movies.

ED: Reading Blonde, it seems like you did a vast amount of research. How did you locate your version of Norma Jeane from all of that material about her life that’s out there?

JCO: Well, I actually didn’t read that many biographies because I started with this photograph, and then I read a biography that just happened to be at the library that day. But then what I did was I went to her films and I saw all her movies, starting when she was just a starlet.

She had very small roles in movies that are forgotten now but Niagra was the big breakthrough that made her a star; a sex object. She plays a voluptuous, beautiful woman and then, after that, she never played a role like it again. She sort of got shunted into this dizzy Gentlemen Prefer Blondes character, so she never really had a chance to develop as a strong screen actress.

“You can be very famous but be very lonely and not have a domestic life” – Joyce Carol Oates

ED: I once heard you describe trying to access the ‘poetic truth’ of Marilyn Monroe’s life as opposed to documentary truth. I wondered if you could maybe elaborate on that idea?

JCO: I didn’t find it difficult to imagine Norma Jeane Baker’s interior life. I think most orphans and people who've lived in a succession of foster homes just become marginalised people, and they’re outside of a family looking in. They don’t have the feeling of being wanted or accepted that most of us have from having a loving family. I really could relate to that.

She did keep a journal, she wrote little things in a notebook. So she had a side of her that was actually literary and poetic and thoughtful, but it was something that it wasn’t really productive to develop because people were not interested in that side of her at all. But people who knew her said she was always reading a book, she was reading novels, she was a thoughtful, intelligent person who had to spend most of her time in a very extroverted way, you know, caring about her costume, her hair and that sort of thing.

ED: What else did you find so alluring about Marilyn Monroe, or Norma Jeane Baker, as the subject of a novel?

JCO: Well, I wasn’t at all interested in the career of Marilyn Monroe and I didn't know much about her, but I had seen a photograph of Norma Jeane when she was about 16 years old and it just really won my heart. She has brunette hair, she’s quite pretty, but not glamorous. She doesn’t look like a movie star. She has little artificial flowers in her hair, she’s very sweet. And I really wanted to write about that girl, I wanted to look into her childhood, and then I wanted to write about how she moves past being Norma Jeane and goes into this dimension of being Marilyn Monroe, where she lost her private self. You can be very famous but be very lonely and not have a domestic life.

ED: There are moments in Blonde when you seem to deliberately obfuscate some of what are considered the known facts of her life. I wondered if you intentionally wanted to preserve her secrets and her mystique, in a way?

JCO: Well, when a person becomes a celebrity, there is such a fragmentation of personality. The only people who really know us well are people who knew us when we were teenagers. People who go on to have public careers start moving in different circles and meeting people who don’t really know them. And so there’s always this sense of performance. And I think that Marilyn Monroe or Norma Jeane, I think she got really, really worn out and burnt out and exhausted. That’s one of the reasons she was always very late for engagements. She was anxious about leaving home. It was really very frightening and pathological, because every time she went out, she knew everyone was staring at her and making up stories about her: ‘Well, I saw Marilyn Monroe last weekend and she looks awful.’

When she was out in the world, she was just kind of helpless. I think she needed a strong protector. For a while, this was her Husband Arthur Miller, but he kind of gave up on her and eventually he betrayed her. He promised he would not write about her but he did. He was writing about her while she was still alive. If you have a husband who is betraying you like that, I think you just are so depressed. He wrote about her in a way that was just devastating. I was very upset to see that play.

ED: After the Fall?

JCO: Oh, yeah. I actually forgot the title because I found it so offensive. I don't know how a husband could do that, even a divorced person.

ED: Is that a dimension of our fascination with figures like Marilyn Monroe, the sense that they need rescuing? And that we could’ve saved them, we could’ve loved them enough, if only we’d been there?

JCO: Well, you know, the interesting thing is we’re only talking about Norma Jeane Baker here. You know, she was actually two people – one was Norma Jeane, and the other was a performing artist. But I think the people who knew her best and I loved her for herself were the people at the Actors’ Studio [in New York City]. She was studying, she’d be dressed in jeans, or she would have a man’s hat on or a sweater, no makeup. She was sort of like one of them and I think those were the people that she might have made a life with. Unfortunately, she went back to Hollywood, where everybody feels inferior and everybody is always comparing one another. I can’t even imagine living that way, it’s not a recipe for happiness. Celebrity is sort of like a nightmare that most people don’t have to endure.

“Celebrity is sort of like a nightmare that most people don’t have to endure” – Joyce Carol Oates

ED: Do you think there’s anything particularly timely about the release of this adaptation?

JCO: Yes, lots of ways in which it is quite timely. It’s just an amazing accident, really, but the whole #MeToo movement has been embodied in the movie. There’s a character in the novel and in the movie who is a producer exploiting starlets and young women who were so anxious to have a career. It’s the sort of thing that came out with the Harvey Weinstein scandal … all these wonderful actresses having to be in bed with this hideous, powerful man. It’s just part of her career, but Norma Jeane had to do that. We wouldn’t know Marilyn Monroe’s name if she didn’t make herself sexually available to these horrible men. That's the way it was.

ED: Are there any particular moments when you saw the first screening of the film that really stayed with you?

JCO: Well, when she has been taken in to see this producer – who is based on a real person – she looks so frightened. She thinks she has an audition but then she’s taken into this man’s office and the look on the actress’ face – if you’re a girl or a woman, you identify with it. That sequence was really painful. And near the end of the movie, when she’s in a hallucinatory phase, addicted to barbiturates. That’s like a nightmare, I found that very hard to watch. I found it very brilliant, but the movie is not a simple-minded, feel-good movie. It’s an Andrew Dominik movie.

Blonde is in cinemas now and on Netflix from September 28.