A bizarre cinematic trip through power struggles, erotica and painful indigestion, writer-director Peter Strickland talks about Flux Gourmet and why the film is “a metaphor for how much you expose yourself to the world when you make art”

On a mission to create electrifying sensory performances anchored in sound and cookery, a ‘sonic food’ collective gathers for a funded residency within a Georgian confection of a house. Add ample scatological references, various ongoing power struggles, a handful of outlandish costumes and one schoolboy fantasy about a buxom blonde egg-laying chef and you’ve got more than the bare bones of Flux Gourmet, writer-director Peter Strickland’s latest film.

You might wonder which curious outpost of Strickland’s imagination produced such an extraordinary concept. The truth is, that Flux Gourmet is firmly anchored in Strickland’s own life; he really was once in a group called The Sonic Catering Band, which went on residencies dedicated to honing their niche craft. “It might be eccentric but we did that for real,” he says. “The film is about looking back on one’s younger days, discovering creativity and everything that entails. If you strip away the eccentric nature of what this band do, it is about people making things.”

This is Strickland’s fifth feature film – and as well as bubbling, sizzling pots and pans – this buffet serves up erotica, horror, revenge and the agony of acute flatulence, which, somewhat incredibly, is the cornerstone of the film. Strickland wrote Flux Gourmet in “two or three months” at the end of 2018 and admits it was pretty hard to sell – which is saying something, given his form for creating brilliantly unsettling film such as 2018’s In Fabric and being described as “cinema’s elegant poet of fetish and rapture and oddity” by Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw.

“The tricky thing is that so much of the tone is in the acting,” he says, praising actor Makis Papadimitriou for providing the precise dimension needed for all the gastric discomfort his character, the quiet, shy Stones endures. “On the page it reads like a frat boy comedy – an early 1980s Animal House and it was putting people off. [Potential financers] said ‘we’re disappointed in this, we’re not into fart jokes’ – which was fair enough.”

Stones is an observer and a recorder – always slightly behind or on the outside. He is a man alone, and his digestive woes are suffered in silent agony. It is testament to Strickland’s skill as a filmmaker that this plot thread didn’t descend into base lavatorial comedy, as well it might. With all of the gastric misery that is central to the film’s narrative, it’s perhaps natural to consider metaphor and hidden meaning. But Strickland is literal, listing food-related health problems – including Coeliac disease and IBS – that are little known or misunderstood by society. “Not only was I ignorant but it’s not really being dealt with in cinema,” he says of the film’s focus on the stomach. “And if it is, it’s done as comedy and so I thought here’s a space to take what you’d normally associate with humour and see if we can treat it in a more solemn, dignified manner.”

What was his overarching hope for Flux Gourmet? “I look for catharsis,” he says, adding that he also wanted to confront taboos. “And maybe the audience would ask themselves why this is a taboo?” He is talking about both the taboo of sex – “it’s so interesting how we completely accept extreme violence in films … but to have pleasure on screen you’re always up against resistance” – and of intimate health issues. “A film can’t cure you of disorder or autoimmune issues but a lot of the trauma people go through is not just about the bodily side of it. It’s the mental side of it – that you can’t talk about it because it’s shameful or embarrassing.” He would be pleased if, for example, the gastric theme in Flux Gourmet gives anyone else suffering a sense of comfort.

The film was shot in just 14 days – short by any standards and fraught with time pressure. In terms of the filmmaking process, he likes the beginning and end: the writing and the sound design respectively. “When you write, it’s the best film ever and when you shoot it’s the worst film ever. It’s a huge deflation when you shoot. It’s a comedown.”

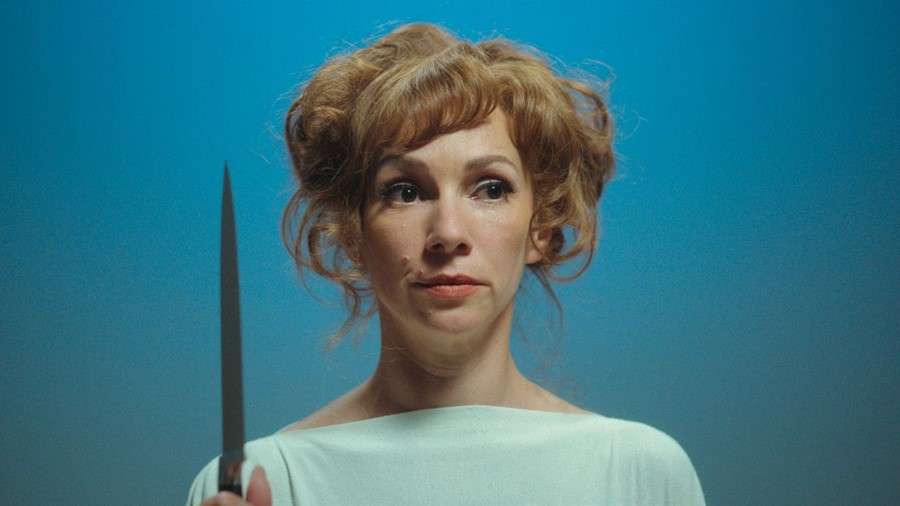

He has already worked with Gwendoline Christie (who plays Jan, the host) and Fatma Mohamad (Elle, the band’s attention-seeking leader – Mohamad has starred in all five of his films), and wrote their parts for them. (Jan’s outfits – silk bunny ears, full skirts, high necklines are uncanny and commanding – were designed by Christie’s partner, Giles Deacon). The power struggle between the two women is central to the plot and something anyone who has ever worked on a creative collaboration will identify with. “I have been in those situations,” admits Strickland. “But I didn’t want to turn this into a vendetta film and [be on the side of] the poor bullied, cornered artist. If you take a side there is no debate afterwards, people just get spoon-fed.” As a result, most of his characters are unlikable: “I made everyone look bad, except Stones.”

Given the scatological reference, the extraordinary costumes and the unsettling dreamlike dialogue – you’d be forgiven for thinking Strickland likes to shock. “I have no need to shock, personally,” he says. “Shock value is, or can be, a cul-de-sac and it’s the easiest thing in the world to do. I don’t see the point. I was not into this edgelord thing where you try to provoke.” Does he worry about audiences walking out? “People walk out – it happens – but people walk out of Disney films as well.”

Strickland currently has two films in development and writes for hire, splitting his time between children’s TV shows, script polishing and ghost-writing. He says he would like to write a good old-fashioned romance, but “when I suggest it people look the other way. They just want me to make horror.” And why wouldn’t they when he serves up such gruesome, sinister stuff? He states that his job as a filmmaker is to always try to make things worse for a character.

“A colonoscopy is bad enough but to have it in front of an audience is truly nightmarish,” he says of one of Flux Gourmet’s most appalling scenes. “It was a metaphor for how much you expose yourself to the world when you make art.” Stones, in voiceover, describes the experience as “something so private sacrificed for the sake of art”. This, admits Strickland, is a concept he is always wrestling with: “Making films is a game of hide and seek.” And as the final performance in Flux Gourmet is underway and the ultimate recipe produced and served, you see exactly what he means.

Flux Gourmet is released in UK cinemas on 30 September.