“It was truly the blueprint for every film moving forward”: as Take Out is re-released this month on Criterion Collection Blu-ray, the director delves into this early gem of his oeuvre

For his iPhone-shot, rainbow-hued slice of life Tangerine, Sean Baker spent months around the intersection of Santa Monica Blvd and N Highland Ave in LA, often in the fastfood joint Jack-in-the-Box, getting to know a community of transgender sex workers. It was an immersion that led him to meet Kitana Kiki Rodriguez, who not only became Sin-Dee Rella, the indomitable star of the film, but also provided the seed of its plot, when she declared her boyfriend might be cheating on her. When the director turned his camera on the hardscrabble, precarious lives of America’s families of “hidden homeless” in the sun-bleached motels of Orlando for The Florida Project, he consulted with motel managers and child-protection agencies, bringing a tangible authenticity to a story he shot from its kids’ perspectives. But those deep dives go hand in hand with Baker’s ability to embrace chance, serendipity and happy accidents on-the-fly – when the motel he’d chosen as The Florida Project’s location was given an eye-searingly bright purple makeover just before production began, he went with it, and when helicopters began thudding overhead taking vacationers on skyrides, he incorporated them too.

Rewind to 2004, and the prototype for the director’s style, its combination of compassion and curiosity about the unseen stories of lives lived on the fringes of US society, is all there in his early jewel of a film Take Out, restored and re-released this month on Criterion Collection Blu-ray. Co-directed with Shih-Ching Tsou (she has produced the majority of Baker’s films, and performed acting, costume design and camera work duties), it’s a day-in-the-life story of an undocumented Chinese delivery rider crisscrossing Manhattan against the clock to earn enough tips to pay his smuggling debt to a “snakehead” gang by nightfall. Shot for less than $3,000 on a Sony PD150 DV camera with a tiny, nimble crew and a cast of both actors and non-actors, it channelled the filmmakers’ love of 70s New York gritty realism – Panic in Needle Park, The French Connection, The Taking of Pelham 123 – and has all the energy, spontaneity and empathy Baker is now feted for. “Looking back, Take Out was truly the blueprint for every film moving forward,” he says from his home in Los Angeles – behind him are a few of the many vintage film posters he’s been collecting since his teens. “We were sort of making it up, discovering this way of working just by doing it: let’s go introduce ourselves and try to entrench ourselves into this community enough to be able to do this in a respectful and responsible way.”

He and Tsou were living above a bustling Chinese restaurant at the time; watching its delivery riders come and go, day and night, rain or shine, gave them the idea of crafting a snapshot of post-9/11 New York through the eyes of one of those workers as they delivered sweet-and-sour chicken to addresses that span from the projects to doorman-buildings on the Upper East Side. Tsou began talking to the restaurant’s staff, learning about their routines and struggles. “We were very lucky,” she says over Zoom from her own LA home. “We found people who were willing to tell us their stories: how many years it would take them to pay off their debt, how much money they owe when they come to the US – we’d fact check it all with them and integrate it into our story.”

Baker adds: “They even let us shoot in their apartment, where seven undocumented immigrants were living. They opened their worlds to us, and that made all the difference.” The more the pair discovered, the more Take Out’s focus began to shift towards the plight of New York’s undocumented immigrants, the mostly-unnoticed labour that keeps the city ticking. They cast their lead, Charles Jang, after holding auditions on the street, and collected his customers by posting an ad on Craig’s List offering to pay $5 to anyone willing to be filmed in their own doorway receiving take-out food. A Chinese restaurant on 103rd Street and Amsterdam Ave agreed to let them shoot and production began in 2003, during the rainiest June on record at the time – a lucky break that lends a richness to the film’s colours, magnifying neons and making shimmering reflections of the city’s streets: “The forecast was nonstop rain for the next 30 days, and where every other New York crew were shut down that month, we were waking up every morning seeing the dark clouds and going, ‘we’re blessed’,” Baker says.

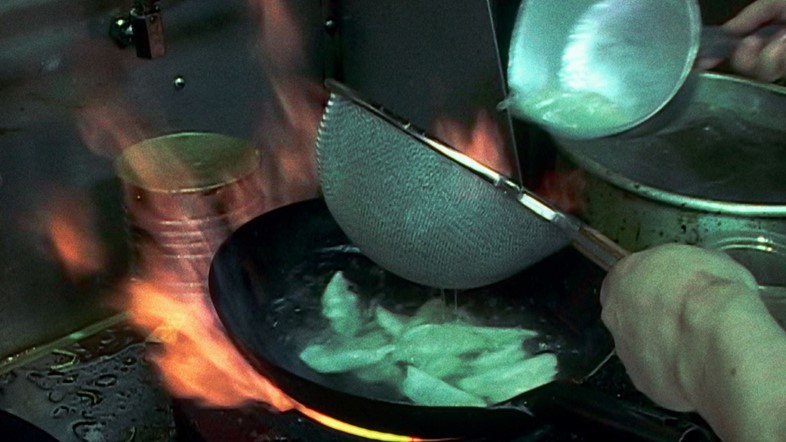

There was no budget to shut the restaurant down while they filmed, so they shot through its frenetic working days, filming real customers’ interactions and altercations, being careful to keep the faces of any undocumented staff out of the frame. Outside, they tracked their protagonist Ming Ding as he frantically pedals the soaking streets on a rickety bike, encountering a kaleidoscope of New York lives glimpsed in the brief stretch of time between receiving a bag of takeout and bestowing (or not bestowing) a tip – most clients oblivious or indifferent to the reality of his gruelling existence. “We were going all over the Upper East and West Side, meeting people for the first time in their doorway. We’d have a brief conversation and gauge their persona and figure out what would work best – belligerent, sympathetic, aloof … ” Baker says. “It was hybrid filmmaking, blurring that line between what is real and what is fiction, showing up in somebody’s apartment and having to incorporate however they were into our script in about 30 seconds.”

The scrambling pace and unpredictability of Ming Ding’s day makes a New York thriller out of the minutiae of the city’s messy everyday lives. And, via a random act of violence, the filmmakers skewer the notion that hard work alone puts the American Dream within reach. Almost two decades later, amid zero-hour contracts, feverish debates around immigration, and a pandemic that has only served to inflame rhetoric (and highlight our ever-increasing reliance on delivery riders), the questions Take Out raises feel as urgent as they ever did. “We were presenting what we considered to be a very objective look at this gentleman’s day, taking politics out of it,” Baker says. “Unfortunately, 20 years later, there are still men and women out there like Ming Ding, struggling on a daily basis to achieve this ‘American Dream’. In 2021 in the US, border crossings increased substantially and there’s even more focus on it now. Sadly we’re still dealing with this stuff and there seems to be no solving of these issues.”

In 2004, when Take Out premiered at Slamdance, audiences saw the result “of me pressing export from my Final Cut Pro,” as Baker puts it. Today, thanks to the Criterion Collection’s 4k digital restoration, we get to see it as the filmmakers always intended: “It’s like a miracle that this little $3,000 film is now part of the most prestigious collection of films in the world,” Baker says. “Shih-Ching and I are finally able to present this film to the world the way we wanted it to be seen.”

Take Out is on Criterion Collection Blu-ray from October 17.