As her first film is released via MUBI, the American artist-turned-filmmaker talks about turning her personal experience of racism into a cinematic, art-world satire

When you think of the cultural atmosphere that makes up an art school, you might imagine a bustling hive of activity intent on harbouring creativity. But for many Black students, the environment can be degrading and detrimental, filled with culture vultures that feed on and appropriate Black culture. It’s something that American artist and director Martine Syms experienced first-hand.

In 2017, Syms graduated with a Master of Fine Art from Bard College in New York. Navigating academia at the time was a dreadful experience for the artist, who describes the college as one of “the most openly racist” environments she has worked in. She quickly became one of the people – out of a small pool of students of colour at the institution – to highlight the tug of war between being glorified in these spaces, while simultaneously experiencing racialised trauma.

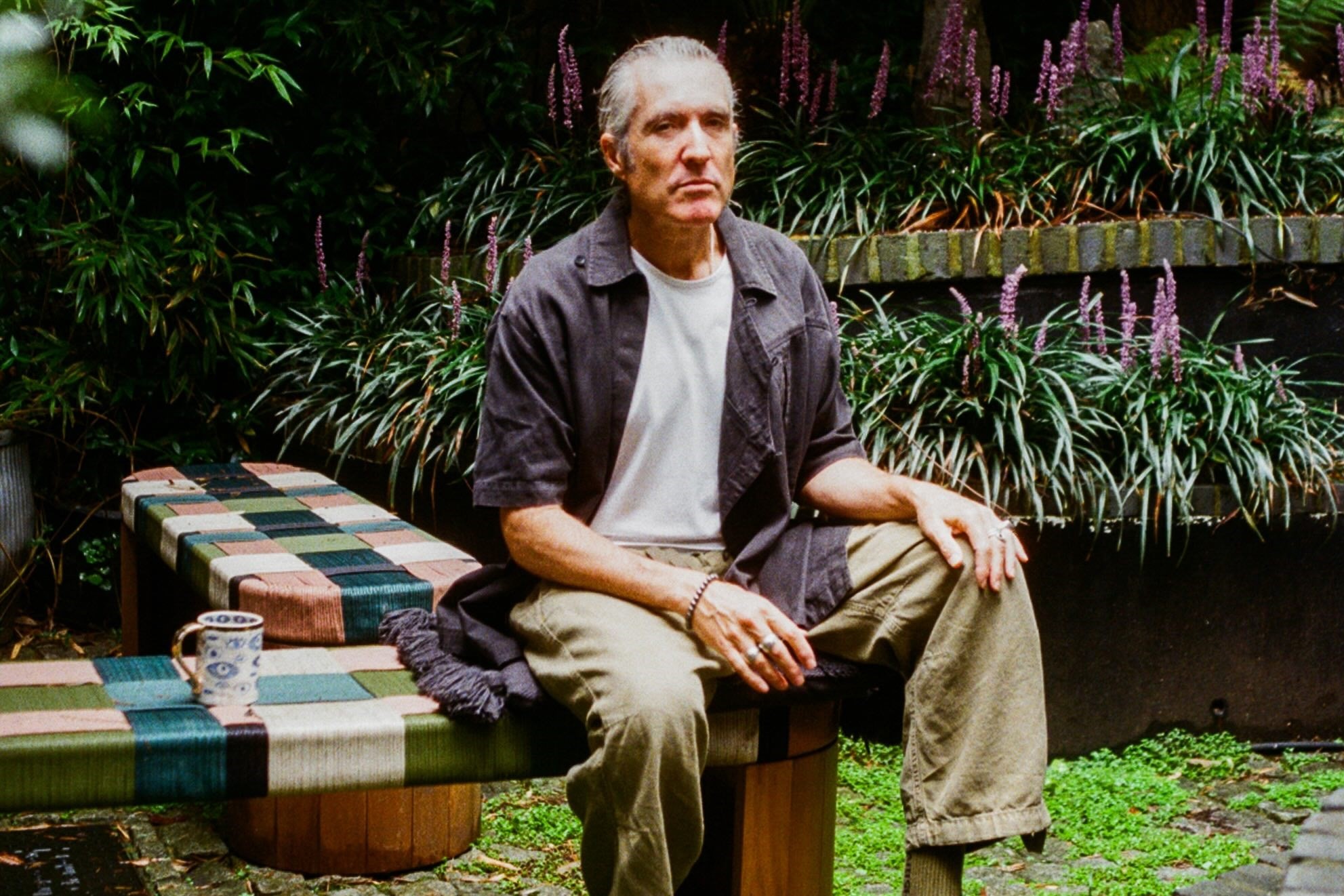

Despite being exposed to a hostile milieu, Syms continued to thrive. She went on to become a popular writer, producer, director and artist, blending theoretical grit, social commentary and humour in solo exhibitions at Tate Modern and collaborations with Prada. At the same time, she was also the head of Dominica Publishing, an imprint devoted to exploring and celebrating Black aesthetics. Syms never let the racism and bigotry she faced define her.

Syms’ debut feature film, The African Desperate, is a coming-of-age comedy and liberal art-world satire about Palace Bryant (Diamond Stingily), a Black MFA student in her last 24 hours of art school. In a wholesome and nourishing conversation one Friday evening in Kings Cross, AnOther spoke with Syms about the film’s Black feminist roots, as well as the flaws and prejudices inherent to the art scene.

Emmanuel Onapa: The African Desperate is your debut feature as a director – how was that experience for you emotionally?

Martine Syms: It’s changed me in a lot of ways. I’ve made films for a long time, but I’ve made them with almost no crew. However, I’ve worked on other projects that were other people’s projects, like for brands or jobs I had before; this was the first time I realised my vision on this kind of scale with this kind of level of collaboration, and it was amazing. It required me to learn how to ask for help and solve problems. But the most exciting thing is that I’ve been working more with actors over the last few years. I’m just so excited to continue working with actors; it adds so much dimension to performances and makes me think about things in a new way.

EO: Much of your work centres on identity and the portrayal of the self through a feminist, Black cultural lens. How have you focused on that in The African Desperate?

MS: I was excited to explore these themes through characters, as some of my other writing is much more abstract. In many of my exhibitions, there is often a film, but it’s not very narrative. It’s one thing to describe racism to someone, and it’s another thing to try and show what it feels like daily. I think the fact that it resonates with a lot of people is because everyone experiences discrimination at some point. It’s been exhilarating to have other people who identify as Black women or Black femme. Also, people in the creative industry know exactly how it feels to experience this.

EO: Why was it so important that the main character was a Black woman navigating a predominantly white contemporary art world?

MS: It was important to me because it was personal. And I hadn’t seen it talked about in a way that interested me. When a Black woman’s story gets told, it’s one-dimensional. It’s [usually] about how the character must be so good – [how much] they strive and work hard. But for Palace, she’s just an average person. She makes good decisions and bad decisions. And I think I just wanted to show a young Black woman’s life and some of the challenges that come with visibility.

EO: The opening scene is three archetypal, white faculty members discussing the merit of Palace’s graduation work. They talk about her ethnic origin, while pretending to be mindful of radical Black thought. As a writer, what critical thinking were you trying to get viewers to engage in with this?

MS: I wanted the opening scene to typify the critique, which is this strange ritual where art students are evaluated by faculty members who might not care about their work or might not be the right person to consider it. Sometimes they should, sometimes they shouldn’t, and I wanted to open it up with that question. I was kind of interested in just trying to play with the archetypes that are present. In the film, there’s one very condescending professor who comes off as being positive, another who uses theory to frame everything they’re doing, from drinking a cup of coffee to going to sleep – they’re always stating it in theoretical language. And there’s another professor who is quite antagonistic and is trying to figure out how Palace got here, that sort of vibe. I’ve noticed these types of people when someone asks you many questions, but they’re just trying to figure out how you got where you are.

EO: In the film, Palace says, ‘I think there are some things in life that are bigger than art’ – what was the broader meaning of that?

MS: I guess it’s a provocation because I find art very important to me. I think that it’s often denigrated, especially in the US; it’s always secondary, but at the same time, if you’re contending with your basic survival, it’s hard to stay in an imaginative space. I think that imagining, envisioning and dreaming are crucial to a good life, so I believe Palace struggles with balancing how much she is feeling stress and pressure and how much she needs to dream.

EO: Considering the academic, cultural and social critiques that the movie makes, why was it essential that people found joy through its comedy?

MS: I have a very comedic sensibility. I think that holding pleasure and laughter is always crucial for me. There was a line in a piece I saw recently, ‘The key to joy is to practice it.’ So basically, keep laughing, keep observing, and the only way to protect joy is through practice.

The African Desperate is out now on MUBI.