How have people’s lives been shaped by the print matter they collect? In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Paper View, Norwegian publisher, curator and critic Elise By Olsen sifts through the libraries of various cultural figures, learning more about their lives and careers in the process.

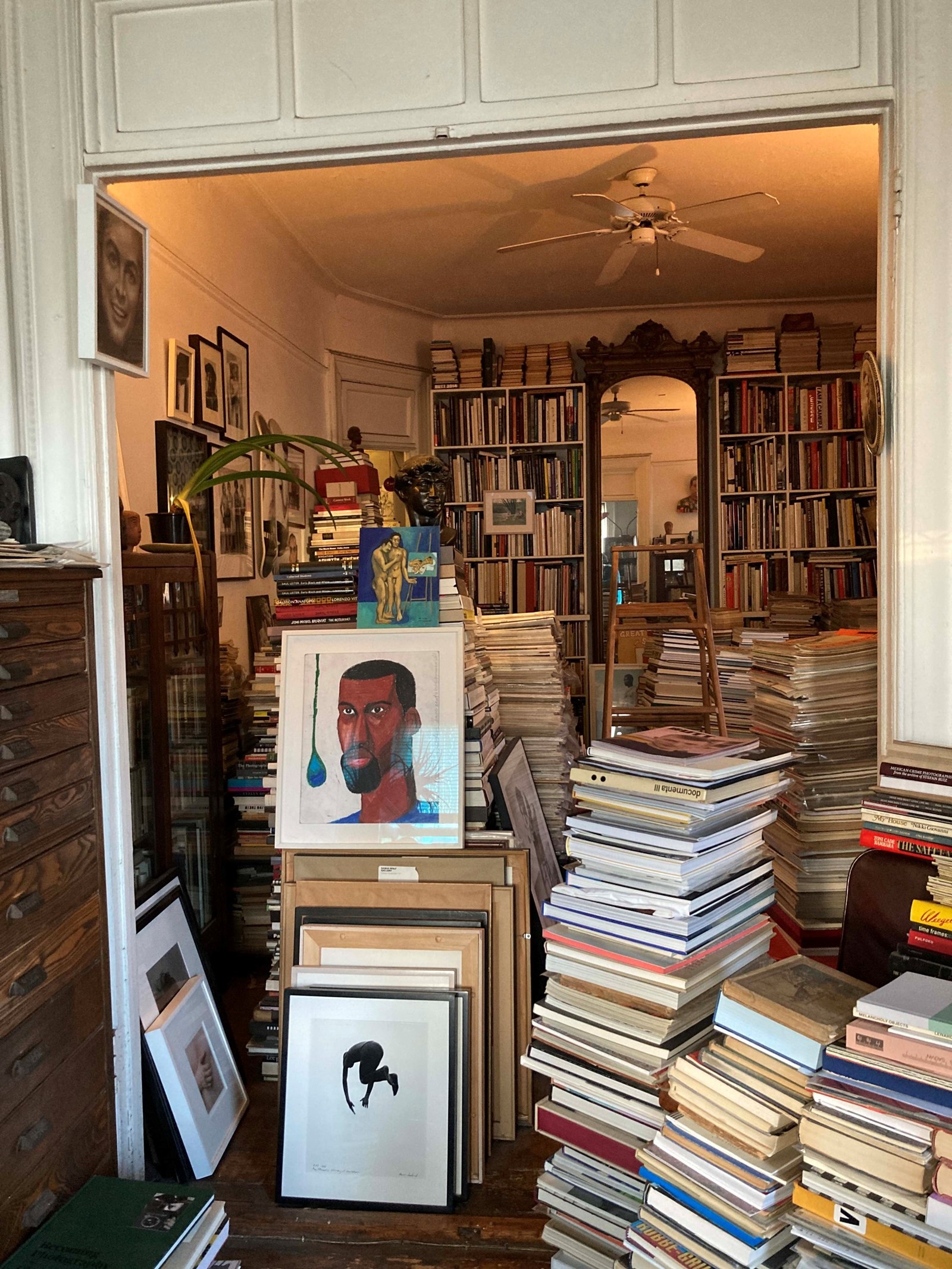

This column begins over a transatlantic phone call in December 2022. Vince Aletti – the American collector, critic and curator – is in his rent-controlled, three-bedroom apartment in the East Village, surrounded by piles upon piles of artist monographs, vintage magazines, prints, tearsheets, newspaper clippings, gallery announcements and other printed ephemera, while I am at my desk in my 16-square metre childhood bedroom in the Oslo suburbs, also surrounded by paper in various forms; in my case, shelved and dusty. Two very chic hoarders … Aletti has just published his 144-page book The Drawer and I have just opened the International Library of Fashion Research in Oslo. Bonding over our love for collecting print, Aletti and I discuss the beauty of seeing a project mature and the relief of letting it go – call it the postpartum glow.

Aletti is currently writing his Christmas cards. “The cards that I have been doing recently have all been vintage. Initially, I was hoping to find old cards from flea markets or eBay that were never used,” he says. “But then I realised that there were so many beautiful cards that were already signed by other people. So I’ve been buying them anyway and adding my signature. I’ve also been buying photos of Christmas trees with people around them, or with children opening presents. I drop those in there as well. They’re little packages of paper images for special friends – partly a gift, partly a card.” I was lucky to receive one last year, in a post-surgery haze, together with a very special American Vogue beauty issue from 1966, Precious and Double-Faced, wrapped in acid-free protective plastic. The card I received was likely from the 1940s; UV bleached with a yellow blush, fresh stamp, and no envelope.

I visited Aletti six months ago on an incredibly hot New York summer day. We sat around his wooden round table, a symmetrically laid out tableau: one can of Coca-Cola and a cup with ice for us both, and analogue aircon: a hand-held paper fan, one for him and one for me. The smell of papyrus drifted around the room, while a Post Malone’s Hollywood’s Bleeding played from the stereo – his third album according to Aletti, who has been reviewing music for decades. It’s as if Aletti applies the tradition of creating Christmas cards to making music mixtapes (or perhaps it’s the other way around?), referencing and re-referencing to create something entirely new.

“There are a lot of magazines I would have a hard time giving up because of what they signified for me, or were turning points for me and my thinking on fashion, music, art, or myself” – Vince Aletti

His home is a paper trail. “There are too many stacks to have a system for each one,” says Aletti. “Some are all [Richard] Avedon and [Irving] Penn duplicates, some are only vintage magazines. L’Uomo Vogue, early House & Garden, Theatre Arts ... or recent photo books that I don’t have shelf room for. Most stacks are completely random, based on size or when they came into my life.”

I realise it’s completely unproductive to ask a collector like Aletti about the necessity, value, desire or function in printed matter. “I have always been drawn to the idea of the magazine. I often carried magazines with me to class as a kid; they were things that I could turn to and read on my own. Looking back, I was super nerdy – it is a bit embarrassing thinking of it now – but I consciously had something in my hands that would signal who I was and what I was interested in. One of the magazines I remember carrying to class was a magazine that no longer exists called The Saturday Review, a literary magazine about new books and writing and publishing; it was an insight into a world I wouldn’t know otherwise.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, British and European magazines weren’t distributed as widely as they are now, but post-college Aletti got a hold of Esquire, early copies of Rolling Stone, and later, i-D and The Face at record stores. “These magazines were amazing to me. I became completely addicted to them. What strikes me, especially with The Face and i-D, was how handmade they seemed to be in the beginning, how funky they were in terms of graphics. They were magazines discovering themselves in a way, magazines coming into their own, evolving, and understanding how they could get better. The ‘do it yourself’ quality of the earlier issues was truly one of their appeals, and was similar to the punk scene of the 70s. It wasn’t something that needed to be so slick or expertly art directed. It was not just a magazine of content, but a magazine that cared about how it looked.”

Once, Aletti generously gave me a copy of Gentry, a high-class men’s magazine from the 1950s about travel, fishing, hunting, horseback riding and arts and culture, published in 22 issues. Aletti also owns copies of Flair, a magazine that existed over the course of one year only (1950-1951) for 12 issues in total, as well as Nest, the infamous interiors magazine published in a run of 26 issues, in different formats every time. “One of the things I have always liked is magazines that had a short life. There are all kinds of reasons as to why magazines don’t last. It’s often because the ones that are putting it together got bored, or they realised that the market wasn’t quite what they expected it to be.” Aletti is talking about how time and speed plays into the idea of creating myth or cultural spectacle – something I’ve always been thinking about with my own publishing projects too, like Recens Paper and Wallet.

I love the idea of discontinuing a magazine (ending on top), although I’m always very sceptical of the comeback (think of Acne Paper, another publishing project that ended after a really strong run, but now has returned in a different form). “I know what you mean, people don’t want to stop,” says Aletti. “Think of all the rock and roll performers who announce their last tour, but then a year later they’re back touring. They just can’t give up. Some people are sensible enough to realise that they’ve run their course.” Although many choose to ignore this fact, the magazine industry is about knowing when to stop, pause or quit altogether.

The moment you decide to stop might be just as important as the moment you begin. I ask Aletti whether he thinks the first issue of a magazine is the hardest one to produce, or the easiest one. “I included a number of first issues in my book Issues. Editors pull out everything they can in issue one. They’re never sure they’re gonna have a second issue, and [so they] give it their all, their best writers, best photographers, best everything. Then they’ve got to keep that momentum going, which is never easy. First issues are always interesting, often they’re statements of intent. They’re letting us know what they intend to do, who they are and what they expect to deliver to us readers. If a magazine is good, it will only continue to get better. The first issue is a jumping off point, then the question is whether it can live on ...”

“For how many years now have people been predicting the death of print? I know it’s endangered but it still seems pretty healthy to me” – Vince Aletti

What is Aletti’s favourite printed object? If not favourite, the most seminal? “Oh God, there’s so many. The answer to that question is usually the [Richard] Avedon cover of the April 1965 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, but I’ve talked about that so much, and there are so many others. A lot of them I included in Issues, like the Diane Arbus images from the children’s fashion section of The New York Times that are extraordinary and super rare. It’s often about a photographer that I’m particularly interested in, or even particular issues of Esquire that meant so much to me when I was a teenager … things that have nostalgic value and personal meaning. There are a lot of things I would have a hard time giving up because of what they signified for me, or were turning points for me and my thinking on fashion, music, art, or myself.”

It goes without saying that Aletti is a living archive in his own right, with a long engagement to thinking and writing about the printed page, having been a photography critic for the Village Voice for nearly 20 years, and a writer for The New Yorker, Artforum and Italian Vogue. He has consistently collected printed matter at the same pace, over the course of many years. “I often buy pieces I already have, with the idea of upgrading or giving them away as gifts.” So what’s the future of print, according to him? “For how many years now have people been predicting the death of print? I know it’s endangered but it still seems pretty healthy to me. Are people really going to stop reading physical books and magazines? There’s so much pleasure involved in both, that I can’t really imagine a world beyond that and, really, I don’t want to even think about it.”

The thing about Christmas cards is that you never really know if they’re going to arrive in time. So what does it mean to spend time on something tactile these days? Writing these Christmas cards – in its effort and expense, or cherishing a declining medium, makes me suspect that Aletti defies the Christmas rush, the tick-tock of time running out, on purpose. Santa’s saboteur … It makes Aletti not just an author, a critic, a collector, and a reader, but what’s more, a postman. And with a few days left for Christmas, I’m impatient, still waiting for my card.