How have people’s lives been shaped by the print matter they collect? In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Paper View, Norwegian publisher, curator and critic Elise By Olsen sifts through the libraries of various cultural figures, learning more about their lives and careers in the process.

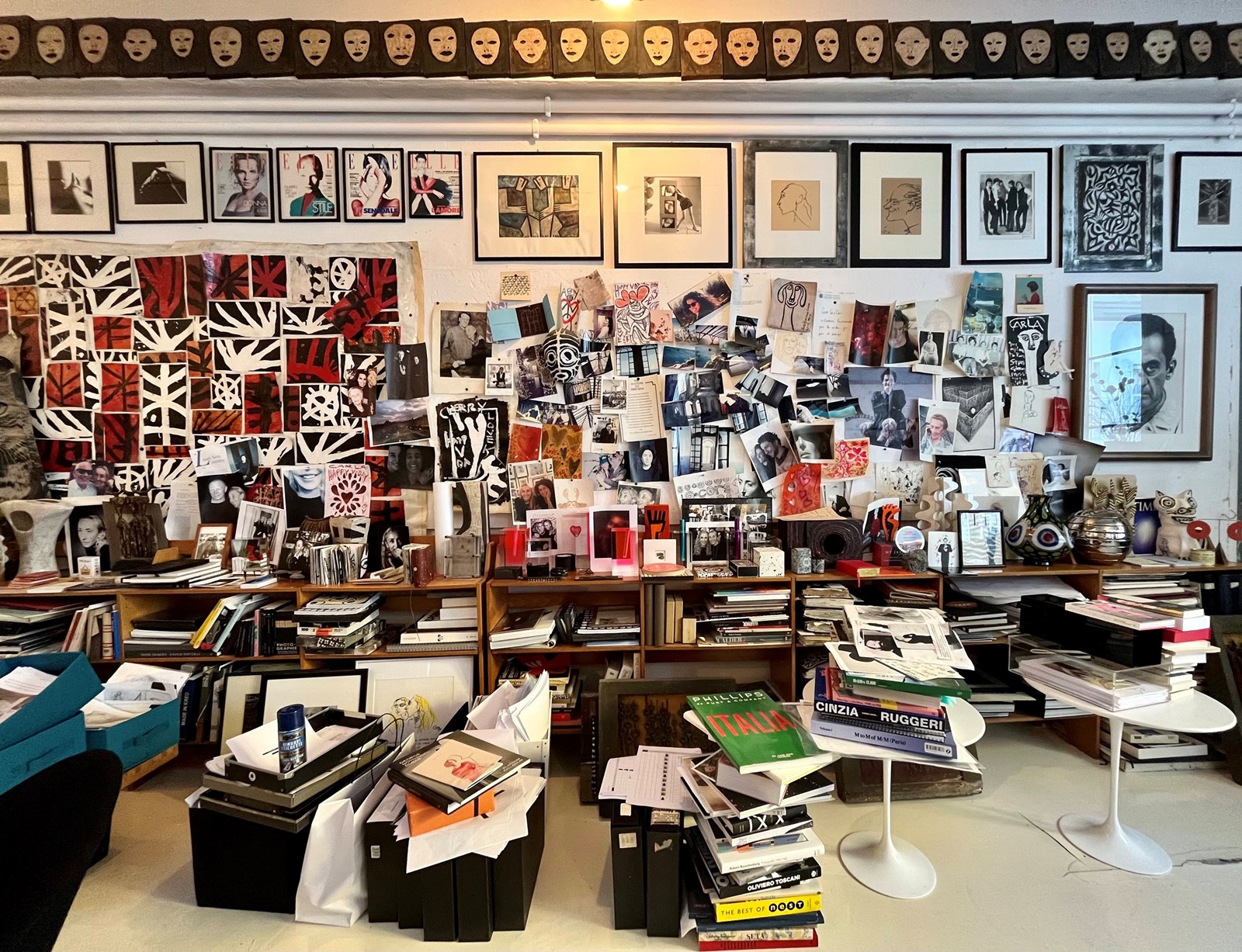

This column continues over a phone call in January 2023. Carla Sozzani – the Italian editor, gallerist and businesswoman – is in the back office at 10 Corso Como, the Italian concept store – probably the world’s first of its kind – that she founded in 1990. She is surrounded by shelves, boxes and drawers of books, magazines, invitations and catalogues; the walls are plastered with illustrations, magazine tear-outs, artworks from friends and personal photographs. It’s an effect that reminds me of the walls of John’s office in A Beautiful Mind – hopefully more healthy, yet just as genius. Meanwhile, I’m in an east Berlin hotel room, “on the other side of the wall”, in bed next to a nightstand with ‘boutique’ travel guides and other bedside literature like Why We Sleep.

Carla Sozzani started working with magazines professionally in 1968, and her passion for paper grew in tandem. She began collecting printed matter, especially paper invitations that had certain meaning or value. “During my years in New York I would visit a little shop in SoHo that sold little brochures, invitations and handmade ephemera,” she says. “It was like treasure hunting. I appreciate the aesthetic value of printed matter and the pleasure of being surrounded by beauty.”

Sozzani had been working with magazines for precisely 20 years when she founded her own publishing company in 1988. “Paper, scissors, glue, and images were always my passion. I really wanted to make books myself,” she says. “Of course I didn’t realise at first how expensive books are to make. It’s incredibly costly to produce a book, which unfortunately is stopping everyone from continuing publishing in print today. Paper has become very expensive.”

The first book Sozzani made was with Paolo Roversi; the second with Walter Albini, a good friend of hers who died very young but who was, according to Sozzani, hugely influential to Italian fashion. “I did books on different subjects, it could be something I was doing in my life, the people I met or an exhibition I liked. As a publisher, I wanted the next book to be different to the previous, not just in its subject or content, but also in aesthetic and form.”

So what is it about paper? “Paper is a passion, a kind of disease, an addiction. There’s something that happens when you touch the pages. In a book you can have all the five senses, which is very rare, and you certainly don’t find it in the computer. The touch, the smell, the sound and sight. Taste, even! You want to eat a book, don’t you? When I get into somebody’s home and I see no books, I think, what kind of person doesn’t have books? That’s strange! It’s a big part of my life.”

“Paper is a passion, a kind of disease, an addiction. There’s something that happens when you touch the pages” – Carla Sozzani

I ask Sozzani how she initially got into publishing. “It’s been going on my entire life. When I was a child I loved making magazines and little journals. It started with school magazines, cutting, gluing, folding. The stapler and the scissors were my tools and still are, along with the photocopier and later, the scotch tape.” I tell her that I used to make books myself, printing out A5 pages, bound with tape and glued on top of a pizza cardboard box to make it hardcover. Sozzani tells me that she still makes book layouts this way before sharing it with her art director, spreads all spread out on the floor. “I cannot really think of the right dimensions by looking at it digitally, I love to change the positioning of images and texts using my hands.” This is real paperwork.

Sozzani publishes, but she’s also a reader. Surrounded by books as a child, an inclination for publishing runs in the Sozzani family. It’s striking that two sisters, Carla and the late Vogue Italia editor Franca Sozzani, have both pioneered contemporary magazine-making in fashion in their own respective ways. “My sister and I used to say that our mother’s reading influenced us very much. She was always reading in an armchair, and learnt a poem by heart every day – she said it was good for her mind. She lived to be over 100.” And does Sozzani write herself? “I don’t have the patience, nor the passion of writing.”

“I read the newspaper every morning. I think I’m one of the only few people left who does. Corriere Della Sera, La Repubblica, La Stampa, and depending on where I am, The New York Times. If I don’t have a newspaper for breakfast I feel like I’m missing a big part of the day. Sometimes I don’t even read them, I just need to hear the sound of the pages turning; starting my day with good vibrations.” And speaking of eating books, reading is a way of digesting (see the definition of ‘digest’: ‘to understand or assimilate new information by a period of reflection‘). “The whole purpose [of reading] is indeed learning, travelling with your mind, giving peace to your mind. You look at the text or the images differently depending on how you feel that day, or where you are in your life.”

In a previous interview, Sozzani highlighted Persuasion by Jane Austen as her favourite book, but now it’s “anything by Dostoyevsky”. “I’m rereading books because people want me to do a book about my very long life,” she says, laughing. “I’m going back to the time when I was very into Russian literature at university. That phase lasted for quite some time.” And that’s the beauty of books – you can put them down and pick them back up when you want to. “The act of reading is relaxing and [being] online is the contrary,” says Sozzani. “My mind gets anxious.”

“If I don’t have a newspaper for breakfast I feel like I’m missing a big part of the day” – Carla Sozzani

These days, it’s rare to receive a paper invitation; they’re now distributed as PDFs via email, so Sozzani stopped collecting them. “With my gallery, I always made physical invitations. That was my way to communicate and express the exhibition,” she explains. “I realised years later that many people have indeed collected them, and when I emailed people saying we were going digital, so many people protested and said that they wanted to keep receiving the physical invitations.”

Does she have a system for her collection? It’s divided by categories, mainly photography, art, design, fashion and illustration. In front of her desk is “the drawer of books I can’t live without”; books that she treasures, that she doesn’t want to lose or separate herself from. It currently contains a catalogue from a past Venice Biennale, books on New York art in the 1970s, and rare copies of photo books that can’t be found any longer. Whether in her home or office in Milan or Paris, she remembers exactly where her books are. And what about storage? “Oh God no! No, no. no. This collection is meant to be used!”

There are even more books in the bookstore at 10 Corso Como and she is very hands-on with the selection. “In many ways, I’m very happy that people still buy books, but sometimes, especially if it’s a rare book, I take it away because I want it for myself,” she says. “That happens at the bookstore here at 10 Corso Como, but also at the Fondation Azzedine Alaïa in Paris [that she co-founded with Azzedine Alaïa’s companion Christoph von Weyhe].” Believe it or not, the renowned retailer doesn’t want to sell books!

Sozanni’s next venture is creating libraries, one at Fondation Azzedine Alaïa with magazines from the 1920s and 1930s as well as Alaïa’s personal archive, and another of her own collection. “Now I have this desire to bring my books together, which I never had before,” she says. “Recently I’ve been thinking about organising them and making a ‘bibliothèque’ so that students and other people can access it. It will take time. I would really like to have one big room where I can be around them all. It’s not a matter of profession, it’s a matter of feeling good.”