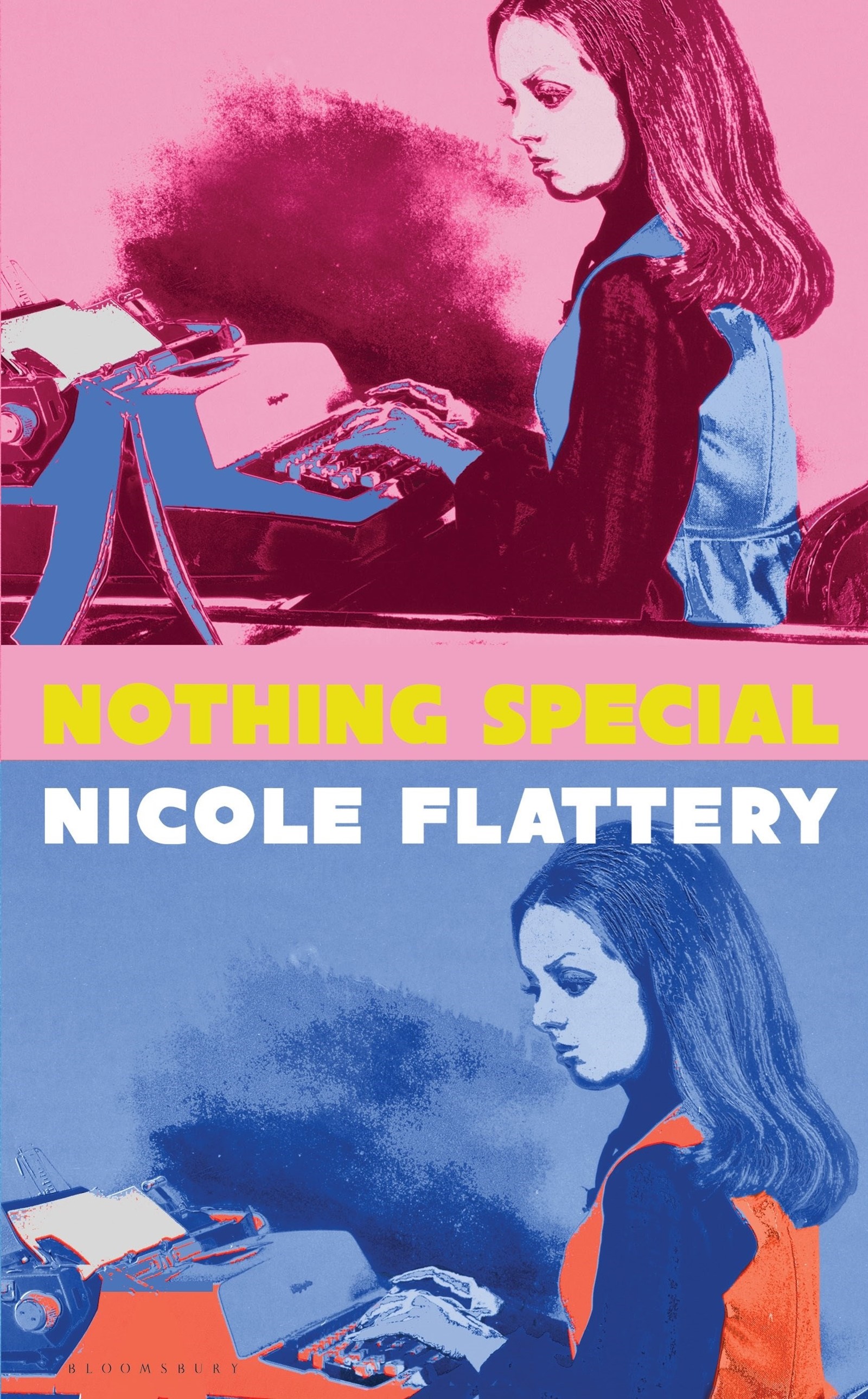

Four years ago, Nicole Flattery’s debut collection Show Them a Good Time won praise for its dark visions of contemporary life and young womanhood within its stories, as well as for the comic depth of Flattery’s own voice. Her second book, Nothing Special, published this month, is her first novel. Set in the milieu of Andy Warhol’s Factory, the novel’s focus is not on the artist himself or his protégés, but on a pair of typists tasked with turning hours of tapes of friends and visitors in conversation into a novel of Warhol’s own.

Flattery based her writing on acres of real primary sources in the form of Warhol’s films, artworks and of course, Warhol’s own novel made up from transcripts titled A Novel and published in 1968. Flattery pitched Nothing Special to her publisher on the basis of a simple one-page outline, and then spent years researching and developing the novel, drafting and redrafting. “For an idea I had to stick with for four years, it was good that I picked something that held my attention,” she says wryly. “Even after all this research and writing, I might have been sick of Warhol, but I still find him fascinating.”

The result of all that fascination is a remarkable novel about what happens between friends, tinged at all times with the threat of social cruelty, of potential collapse. Mae and Shelley stand together on the periphery of the Factory’s glamour, waiting for their lives to be transformed in different ways. Flattery’s distinctive voice, edged with dark humour, returns with a new depth, making the most of the unique time and place she has chosen as the novel’s setting.

Flattery, who grew up in Mullingar and now lives in Dublin, can see the parallels between Warhol’s ’15 minutes of fame’ and the grip social media now holds over so many of us 65 years on. “So many of Warhol’s ideas were genius, even if some considered them superficial or whatever,” she says. “They were so much ahead of his time, certainly the recording and constant documentation that he was involved in.”

In Dublin, AnOther met with Flattery to talk about Mae and Shelley, the transformative power of glamour, and the legacy of Warhol and his superstars.

Ana Kinsella: The book is set in Andy Warhol’s Factory, but Warhol himself is barely in it. He’s this shadow passing through the lives of the main characters.

Nicole Flattery: I wonder what people will think about that – “She was too lazy to write Warhol!” [Laughs.]. But I did that purposefully, because I was thinking about power generally. You never see power; if someone’s in charge, you rarely see them, but everything is directed around them. I really couldn’t make my mind up about Warhol, and I was flip-flopping back and forth the whole time about whether he was good.

AK: It’s the complicated relationship between Mae, the narrator and Shelley, her fellow typist, that lies at the heart of the novel. Their friendship reminded me of Veronica by Mary Gaitskill. Have you read it?

NF: It’s one of my favourite books. I think that female friendship is something that lots of people have written about, so I wasn’t trying to do something totally original. But, I was thinking about betrayal in friendship, and what that can mean, how slight it can be. A big idea in the book is transformation: how, if you get a certain thing or if you become famous, you become a new person – the two of them, Mae and Shelley, are both trying to do that, and they’re just clashing.

A totally cynical view of the Factory is that these were all fame-hungry heathens gathering together to do their drugs and have their orgies or whatever, and I just don’t believe that. I do believe that in some ways they were friends, or they cared about each other. It’s so easy to be like, ‘Oh they were all in it for the photographs or whatever,’ but I don’t think that’s true.

“You never see power; if someone’s in charge, you rarely see them” – Nicole Flattery

AK: Cinema definitely seems to influence your work a lot.

NF: I am always thinking about films. I studied film – I didn’t study it that hard, though it definitely has influenced my writing. I went to see Tár the other night. I was like, ‘This is a perfect film for me,’ because I’m really interested in how the mask slips and you get to see someone’s authentic self. How I found my way into writing books is that I really liked going to the theatre. I studied theatre and I used to write a lot of theatre reviews, so I was always thinking about acting, and how we’re probably all doing it all the time. I don’t think that that’s necessarily a bad thing.

I’m not entirely sure there is such a thing as an authentic self. Obviously I’m fascinated by self-invention too, and I think that it’s a great thing. I think you should be allowed to invent yourself, get dressed up, wear whatever. It’s like, ‘Well, what are we supposed to be doing instead?’ All living where we grew up and wearing sacks?

AK: Is celebrity something that interests you generally?

NF: Oh yeah. It annoys me when people trivialise the idea of celebrity, when they act like it’s not worthwhile to think about. If you think about culture now, celebrity is probably one of the most interesting things to think about – and it’s so hard to do it well. One thing I do mourn, and this also makes me sound elderly, is mystique. That quality of being so hard to figure out – that used to be quite a common quality to stars, but I don’t think it is anymore. I feel like some of the smarter actors have deleted their Instagrams, they’ve tried to retain that mystique. We want to be brought so close to these people that there is no space for imagination anymore. I find that really sad. I imagine being a young actor now is quite terrifying.

AK: I get the feeling a lot of your female characters are, in some way, complicit in their own suffering. Even the superstars in the Factory in this novel are complicit in their own exploitation. Do you think that’s something that runs through your work?

NF: Yeah, absolutely. And I’m complicit in my own suffering all the time. A lot of these characters, like all of us, are quite seduced by the easiest option. I think that it’s extremely hard to figure out who you are. So if all these seductive options are there for you, then it’s so much easier to go along with them, rather than establish any actual sense of self.

AK: I’m hesitant to compare you too much to other Irish novelists of your generation, but that does seem to be a theme of interest to many writers at the moment.

NF: I share concerns with my contemporaries because we are all writing at the same time. There’s a self-destructive strand, people who don’t know what’s good for them. They’ll seek out the bad thing so they’ll make a funny comment about it afterwards. I do that too, maybe, in real life. There’s a line in Nothing Special which I took from a, A Novel, which is ‘Out of the garbage, into the book.’ It’s the idea that the art will redeem your life, essentially, and I do feel that like that’s true for so many of these characters.

Nothing Special by Nicole Flattery is out now.