On 15 August 1951, a small French town went mad. It started with reports of mass nausea and vomiting, but the situation rapidly deteriorated. Within 48 hours, more than 230 people in Pont Saint-Esprit had been struck with a mysterious combination of sickness, convulsions and hallucinations. Then people started jumping out of windows. By the time the dust had settled almost a fortnight later, 50 people were interned in asylums, and seven were dead. A foodborne illness was suspected, and investigations honed in on the town’s bakery – it was said to be a case of pain maudit, or “cursed bread”.

Anyone who has read Sophie Mackintosh’s previous two novels, The Water Cure and Blue Ticket, might guess that this strange story would capture her imagination. It seems to fit the author’s literary sensibility almost too perfectly – like a dark fable, it is suffused with surreality, violence, and the sense that the everyday world can be suddenly overturned and irrevocably altered. That’s before we even get to the troubling theory that Pont-Saint-Esprit was not the victim of a dodgy batch of flour, but of a CIA field test of the effects of LSD, as part of a biological warfare program …

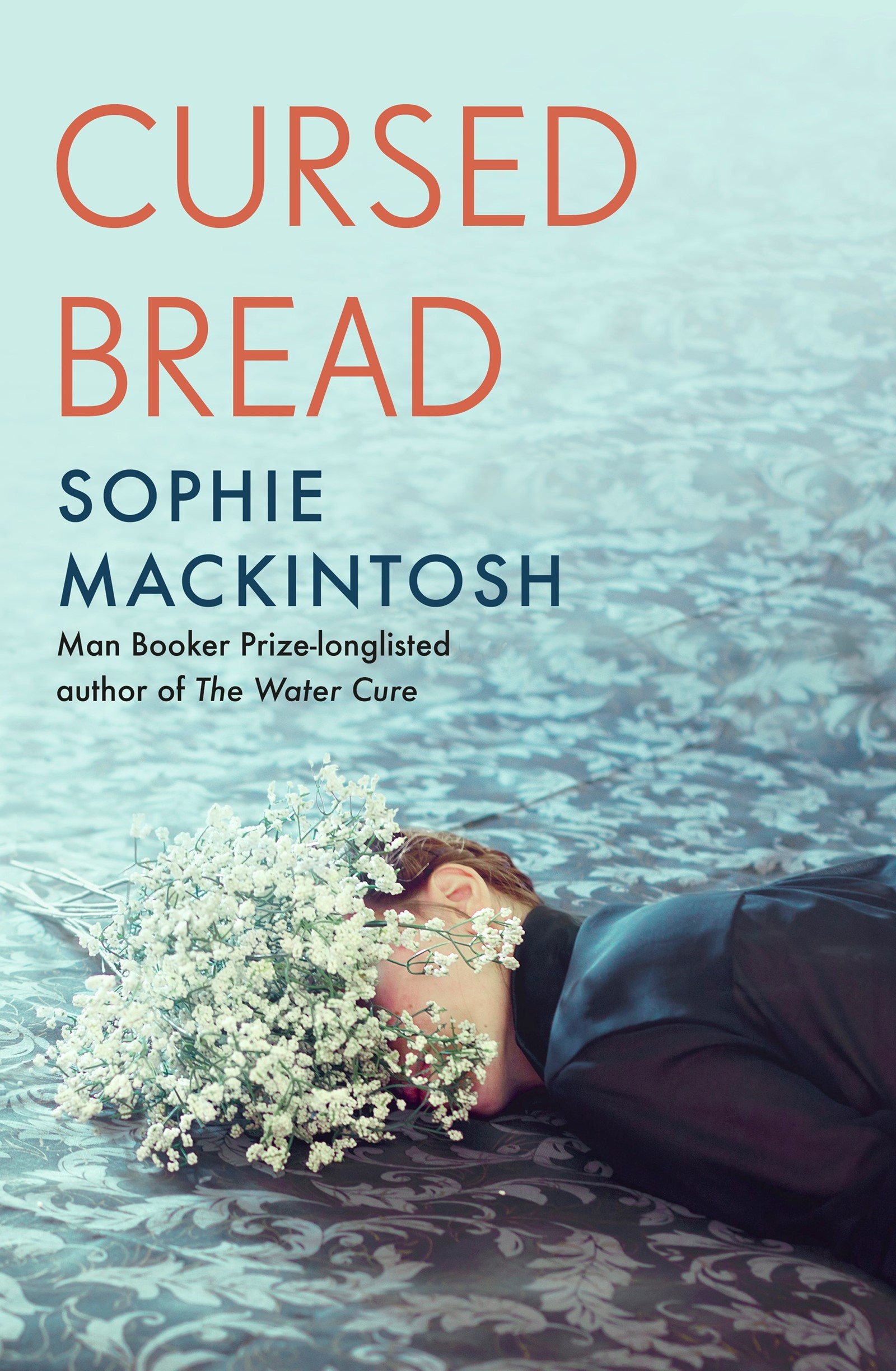

In Cursed Bread, Mackintosh takes this disturbing and mysterious story and runs rings around it, to create a novel that itself feels somewhat poisonous – riddled with secrets and all-consuming obsessions, which threaten to spill out like lethal toxins. We see all through the eyes of Elodie, the baker’s wife, whose sexual, emotional and intellectual unfulfillment collides with the arrival of two enigmatic strangers: the ambassador and his dark-haired, sharp-toothed wife, Violet. What exactly are they doing in the town? Why are Violet’s wrists covered in bruises? And why, since they arrived, does Elodie’s reality seem increasingly unstable, liable to rupture at any moment?

On a grey afternoon in Walthamstow, I spoke to Sophie Mackintosh about speculative history, unreliable narrators, bread, and obsession.

Eloise Hendy: I’m so fascinated by the real-life story of what happened at Pont-Saint-Esprit, and I wondered how you found out about that.

Sophie Mackintosh: It was a few years ago. I was just scrolling through Twitter and it was one of those things – “stranger than fiction! This weird town where everyone lost their minds and hallucinated”, and I was like OK! But there wasn’t much written about it. Maybe there’s been a bit more since then, but I just thought it was such a weird story. And it wasn’t just the actual story itself – even though there was a whole town suffering from hallucinations, which obviously is really interesting – but that there are all these weird theories around it. Maybe it was the CIA, maybe it’s some form of mind control, maybe it really was just poisoned flour. That’s also quite disturbing in itself. You don’t really expect bread to lead to an event like that, you know? Bread is so everyday.

It just sent me into a little wormhole. I kept returning to it, and wondering what I could do with the idea of this town that basically gets flipped on its head.

EH: The story still has this speculative quality, because no one knows exactly what happened. It feels like you’re more interested in getting at the emotion of what could have happened rather than the straight facts, which is quite a different way of approaching a ‘historical novel’.

SM: I wanted to use the story more as a jumping-off point, I didn’t want to just retell it. I’ve described it as ‘historical speculative’. Cursed Bread is so much about the baker’s wife, Elodie, and her feelings, and the relationship between this couple, and that’s all completely fictional. When you’re writing about a real event – and this was really quite a traumatic event – there is a sense of responsibility. I didn’t want to have anything too drawn from real life. Everything is completely fictionalised.

EH: You wrote Cursed Bread during the pandemic. Did it feel very different writing it then, in terms of your process, than writing the previous two books?

SM: Yes the actual writing of it, I was just in the house 12 hours a day and feeling really unhinged, and I think that definitely came through in the book. When I was writing it, actually, [there was this feeling of] everything being tipped upside down, being turned on its head, and the sense of claustrophobia, this sense of not knowing what was real, this atmosphere of suspicion and paranoia. I was like, actually [these events are] not massively different. And in the book, the shadow of World War II is always there as well, and the idea of this massive collective trauma that everyone has lived through already. And so I couldn’t help thinking, we’re experiencing a massive trauma now. What will that do to our sense of reality? What will that do to our sense of how we see ourselves? Covid just showed how easily the wheels do come off. It doesn’t take much for everything to suddenly switch.

“I was just in the house 12 hours a day and feeling really unhinged, and I think that definitely came through in the book ... Covid just showed how easily the wheels do come off. It doesn’t take much for everything to suddenly switch” – Sophie Mackintosh

EH: I love how much of the book is about storytelling, and the instability of knowledge and truth. Elodie admits that, in another life, she “could have been a pathological liar”, and the book opens with her saying “did it really happen like this? And if it did, why not tell it differently?”

SM: It is so much about narrative storytelling. I just think there are so many ways that something can be told. Elodie tells herself a story – she tells herself a story about falling in love with Violet, and a story about what Violet’s life is like. She’s just existing in her own little world, essentially. I was talking to someone recently and they said, “so did she hallucinate the whole thing? Did Violet and the Ambassador even exist?” And I was like no, they definitely existed, but it’s interesting that people would have that response. Although Elodie is such an unreliable narrator, I didn’t see her as completely fabricating other people. But I guess there could be that ambiguity, even if it’s not what I originally intended. I was thinking more about the narratives we tell ourselves about our relationships, other people’s relationships, the life we feel like we should have had, and the life we’re actually having ... she’s [also] so angry at the idea that she can’t know everything she wants to know, and that’s a really understandable impulse for me. It would be nice to know everything about the people we love. But you never actually can.

I think with Violet too – not to say she’s a boring character – but I think obsession and desire can really project things onto people, and sometimes it’s not really the person, it’s the projecting that’s the interesting thing. And they all project so much onto her.

“[Elodie is] so angry at the idea that she can’t know everything she wants to know, and that’s a really understandable impulse for me. It would be nice to know everything about the people we love. But you never actually can” – Sophie Mackintosh

EH: It’s a very claustrophobic novel, but you constantly break up the narrative with letters Elodie writes to Violet in the present. How did you decide on that form, and what was it able to do for you?

SM: I wanted to tell the story of the town, but also knew that I wanted to look back from where Elodie is now. And in that way, sow little easter eggs, or breadcrumbs. It’s a weird space, because if you know the event, you know what happens and what the story is building towards. But then you don’t necessarily know everything, and you don't know what happened to the characters. So I wanted to slowly reveal that information while we’re also learning about the event. The letter form seemed like a good way to do that. Just thinking about Elodie physically writing down her thoughts, and almost trying to explain herself, absolve herself, in a way. She’s telling her final story, she’s having her last word.

EH: Elodie is read as stable and trustworthy, but obviously the reader knows that there’s uncertainty around her all the time. Was that important to you, constantly evoking the gap between what’s hidden and what’s on the surface?

SM: Completely, and the idea of what you don’t see – you only see a part of it and you can totally misinterpret it. She just overhears a little bit of a conversation between the ambassador and Violet, and she just runs away with it. It becomes the basis of an obsession. I just think that gap between what we know and what we don’t know is so interesting to me. You can really let your imagination run away with you. And why shouldn’t Elodie have this incredible inner life? Why shouldn’t she be passionate and want these things? Why can’t she be really intelligent? Why can’t there be this whole part of her that nobody sees and has never really been allowed to flourish?

That’s part of the reason I wanted to have the present-day scenes too, because even though she’s very traumatised, and suffered this awful event, she gets to have some agency at least, and be living in a way this life that she did envy – not even the life she envied in Violet but a different life, on her own terms. In her own space and by herself. I thought that was really important.

Cursed Bread by Sophie Mackintosh is out now.