An exhibition dedicated to the Japanese-American musician in New York proves that, even in comparison to glitch masters like Aphex Twin and Autechre, Tone’s compositions are still radical today

Imagine erratic static, metallic squeals and cacophonous spikes of white noise harsh enough to make you fear for your hearing. It all sounds like a broken CD that’s been crudely reconstructed and shoved back into its player. In fact, that’s exactly what it is. Solo for Wounded is a two-part, 48-minute musical piece by the Japanese-American critic and composer Yasunao Tone. To create the work’s almost unendurable sound, Tone poked pinholes on strips of scotch tape and slapped them on the underside of a copy of Debussy’s Préludes – then recorded the results.

“I wondered if it was possible to override the [CD player’s] error-correcting system,” Tone recalled in the liner notes of the 1997 album, now considered a classic amongst both experimental music-heads and arty academics. “It worked … to my pleasant surprise, the prepared CD seldom repeated the same sound when I played it back again, and it was very hard to control.”

This is a helpful snapshot into the creative impulses of the now 88-year-old artist, who has made a career of turning electronic media against itself. “To fight with smart machines you have to be very primitive,” he once told artist Christian Marclay in an interview. “When he scratched CDs, he changed the world,” explains curator Danielle A Jackson, who organised six decades of Tone’s work into a new show at Artists Space in New York – his first-ever retrospective, Region of Paramedia. Jackson continues, “That opened doors for a lot of composers and sound experimentalists.”

If you’ve read about Tone, chances are it was in the context of glitch – that buggy, hyperactive subgenre of electronic music made popular by 1990s electronic musicians who no doubt looked to works like Wounded for inspiration. But even by the relatively out-there standards of glitch masters like Aphex Twin and Autechre, Tone’s compositions are radical.

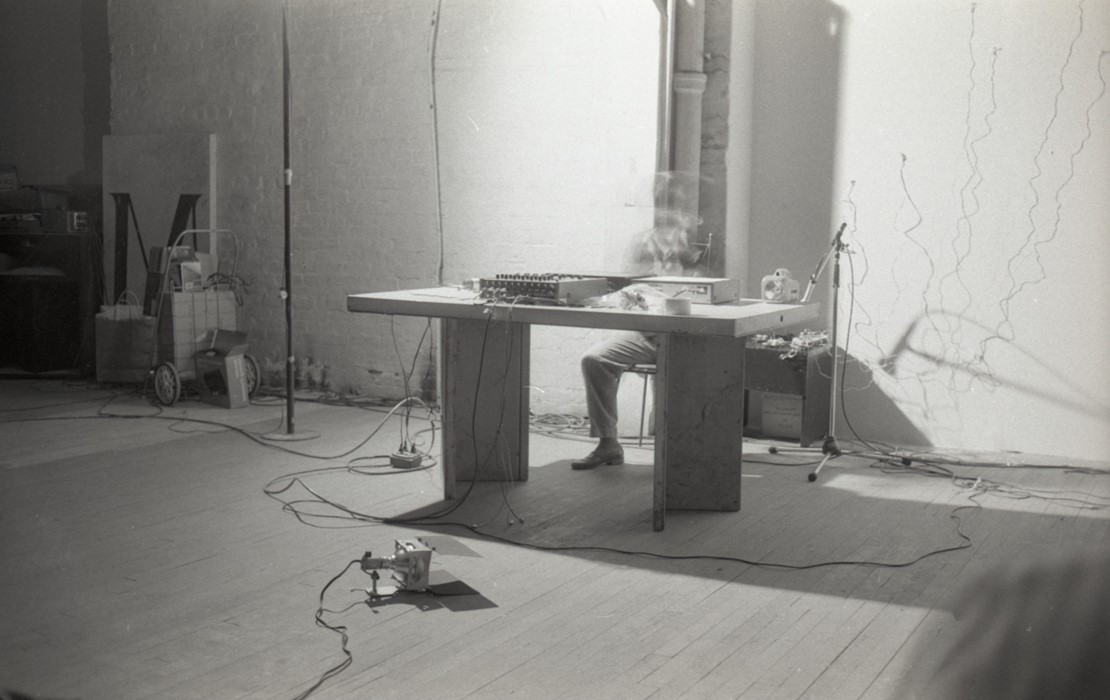

Tone’s work is musical but rarely melodic. And not often is it pleasurable, per se. Common scales, instruments and playing techniques are neglected in favour of jury-rigged electronics and raw synthesised tones. Performing behind piles of wires and innominate machines, the soft-spoken artist looks more like a mad scientist than a composer. “Tone’s whole work has been about really trying to be outside music,” Jackson explains.

Born in Tokyo in 1935, Tone became a staple in Japan’s burgeoning post-war avant-garde scenes after college. He helped found the country’s own branch of Fluxus, and belonged to the improvisatory music ensemble Group Ongaku, the social interventionist outfit Hi-Red Center (which also counted Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik as members), and the early computer-art collective Team Random.

Inspired by musique concrète and the “indeterminate” compositions of John Cage, Tone’s early efforts relied heavily on chance. One piece involved throwing random objects onto the strings of an open piano; another – a choreographic work – saw him tossing water on a stage where a dancer attempted to catch it with a bucket affixed to their head. His 1961 graphic score, Anagram for Strings, comprised a series of small, black-and-bubbles on a grid and a set of ambiguous instructions prompting players to swing between notes of their own interpretation. It looks like a children’s game of connect-the-dots, but it sounds far more sinister – like an enfeebled cat howling in pain.

A six-month trip to San Francisco prompted Tone to move to the US indefinitely. He settled in New York in 1972, and quickly became ingratiated among, and collaborated with, some of the city’s cutting-edge experimentalists of the time, including Merce Cunningham and George Maciunas.

The move, Jackson explained, marked a new chapter for the artist, one that saw him increasingly turn his attention to the ways in which language and image are translated to sound and the various pieces of flawed technology we use to do it. His 1982 installation Molecular Music, for instance, comprised a film screen outfitted with special sensors that turned projected photographs – in this case, pictures of ancient Chinese and Japanese poems – into sounds, with pitch and tone determined by changes in light.

In recent decades, Tone has continued to probe the limits of newer and newer pieces of audio technology. In 2011 came a series of MP3 Deviations, for which the artist built special software to corrupt the titular audio files. The results were even more severe than those produced by his CD interventions.

Later in the 2010s, Tone developed an AI system that learned, through neural network training, to simulate his own unconventional sounds and performance techniques. And sure enough, Tone figured out how to fuck with that too. “He almost has to outplay himself to play something new,” Jackson said, noting that, for pieces like AI Deviation #1, Tone performs against his instincts to confuse the app – effectively treating his own digital surrogate like the old Debussy CD. “He’s always challenging himself like that.”

Yasunao Tone: Region of Paramedia is on show at Artists Space in New York until March 18.