The Canadian filmmaker’s latest project is a pornographic remake of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1968 film Teorema. Here, he talks about camp, the line between erotica and porn, and why there’s no underground anymore

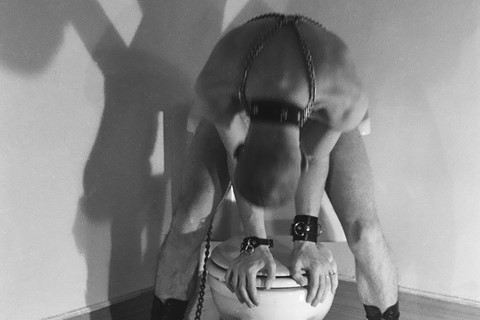

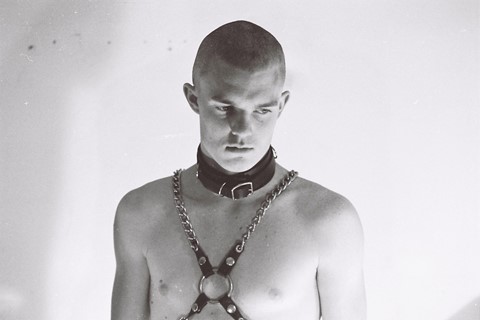

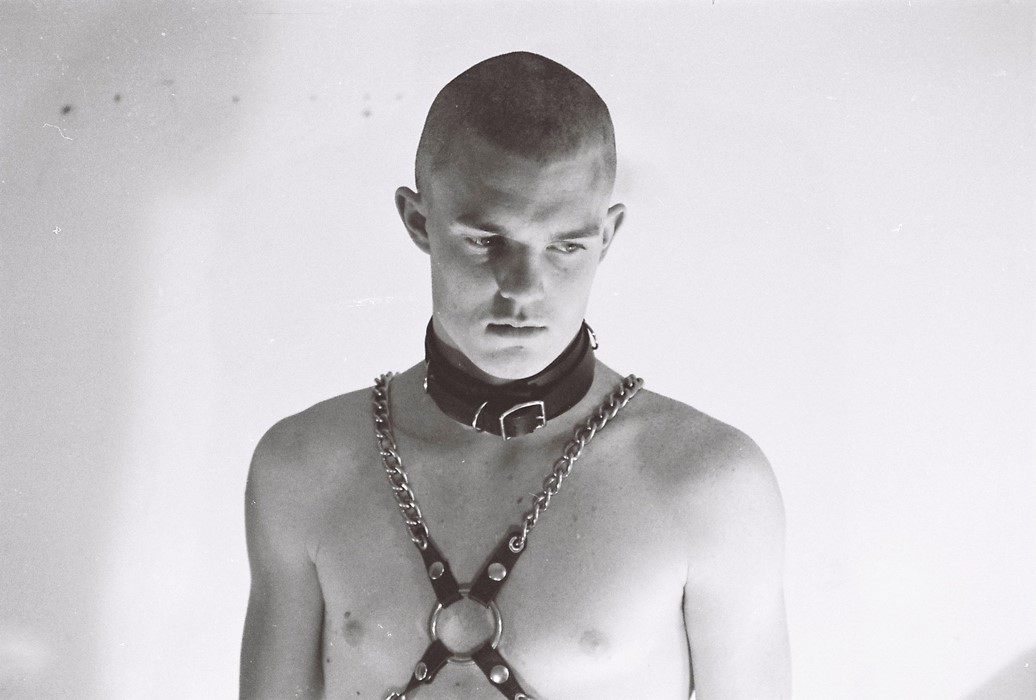

Bruce LaBruce is no stranger to controversy. Throughout his career, he’s pushed the envelope with punk, sexually explicit queer cinema, from his trailblazing debut feature No Skin Off My Ass (1991) to Saint-Narcisse (2020), a darkly comic, twincestuous romance. But now, LaBruce has something new in his sights: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968).

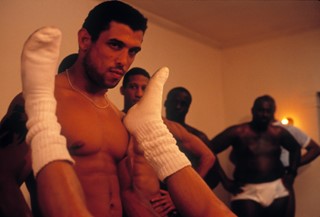

Just downstairs from the room where LaBruce and I have our conversation at a/political – who also serve as executive producers on this latest opus – in south London, a group of people are building sets for his latest film: The Visitor. This pornographic retelling of Pasolini’s classic – in which a stranger visits a bourgeois family and, after having sex with each member of the house, changes their lives – is being filmed on location at the space. And in-between shooting a new film, LaBruce appeared in conversation with Dominic Johnson, Lidia Ravviso and more at Rich Mix, and introduced Teorema at the BFI; this new chapter in his career comes alongside recognition for what came before it.

While LaBruce has been granted entry into esteemed institutions in the past – No Skin Off My Ass has been screened at MoMA – his latest opus shows that he has no interest in either slowing down, or playing nice, as he creates what could be his most provocative film yet.

Below, Bruce LaBruce talks about his early love of film, Teorema, and the tensions in contemporary queer culture.

Sam Moore: What was it that drew you to film initially, and to Pasolini in particular?

Bruce LaBruce: The long story is I grew up on a farm quite a number of decades ago. We had two TV stations and channels. My parents were farmers, very working class; we had a 200-acre farm, and they really liked a lot of movies, especially Hollywood movies. So they would take us all to the movie theatre, and to the drive-in; and they kind of instilled this love of cinema in all of their children. That was the real genesis of it.

While I was in grad school, I started hanging out in the punk scene in downtown Toronto. A lot of people were working in Super 8, and I started making experimental films, punk, and queer, with explicit queer content and sexual content. That was the beginning.

But Pasolini just came naturally. I was exposed to his films in university, because we watched so many films. I think the first films of his I saw were The Trilogy of Life [ones], which I wasn’t crazy about at the time. But I was obsessed with all the queer auteurs: [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder, [Derek] Jarman, [Pier Paolo] Pasolini. All the biggies. And Teorema, I probably just caught it late on TV one night.

SM: Is there something about Pasolini in particular compared to those other directors that resonates with your filmmaking in a way that made you want to tackle a reinterpretation of Teorema?

BLB: I wouldn’t say I’m a Marxist per se – I mean, I’m not that smart, not that directly political – but I’ve read a lot. And Pasolini, what draws me to him, in particular, is his dialectical thinking and the way that he really embraces paradox; the way that he could be a kind of super religious spiritual person and a hardcore Marxist at the same time; how he could be queer and make a film like The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964); how he was totally anti-materialist but made these lavish big budget films. All those convictions.

SM: What is it that drew you to making Teorema in a more sexually explicit way?

BLB: Quite often, part of my methodology is queering texts that have a homosexual subtext, and then I bring it out and exaggerate it. Or in a similar vein, I also do pornification. So it’s the same kind of idea, and then combining the two. And I’ve interviewed a lot of filmmakers, big, famous filmmakers who always said that the one thing that they really wanted to try was porn.

SM: Like who?

BLB: Paul Verhoeven; Joseph Stefano, who wrote Psycho (1960), and wrote and produced The Outer Limits (1963-1965). And I think John Waters has talked about it, and his early films are verging on porn.

SM: Over the last decade or so, there have been more films that might traditionally be taken seriously with real sex in them, like Dogtooth (2009) or Stranger by the Lake (2013), that ask where you draw the line. Is the line between pornographic and non-pornographic even useful?

BLB: The line’s always been there, it’s kind of this tradition of making the separation between erotica and porn. Pornography is always the last frontier I think. One of my pet peeves is that when explicit sex is shown in a lot of art films, it has to be shown as something grotesque. It can never be “sexy people” having really erotic, pleasurable sex. In most art films, sex is shown as something ugly or disturbing.

SM: So because it’s not there for pleasure, they’re able to say, “we won’t call this pornography?”

BLB: Yeah, and the audience is more encouraged to be repulsed by it than turned on by it.

SM: Do you try to turn people on with your films?

BLB: Yeah, and I think that’s why I’m dismissed by some people as being “too pornographic” because I work more inside the porn idiom that you’re supposed to; that I show full sex scenes and scenes of penetration; that I put an emphasis on the explicit sex in a politicised context – but the function of it is still to arouse people.

SM: In Pasolini’s Teorema, there’s this idea that the stranger and the presence of sex break down this family unit, with sex being used to radicalise.

BLB: What I find interesting about Teorema is that sex is the catalyst, and it has a kind of healing function, as sex work has. But in the film, it’s almost surprising that he doesn’t make it more pornographic; it’s just implied that the characters are having sex. So what I’m doing is almost like extending his work to its logical conclusion. I was worried that my script was too slavish to the original, but with the cast we have, and the scenes we shot, they’re definitely leaning into the camp.

SM: What would you like to see from the current or next generation of queer filmmakers? What is queer culture missing?

BLB: It shocks me that movies still lean in so hard to all these outmoded gay narrative tropes: coming out, coming of age; very identity-oriented representations of gay characters. It’s much easier to represent a gay boy who’s repressed in high school and comes out and makes friends. It’s very mainstream, and kind of played out.

SM: Do you think that, over time, the idea of what’s “underground” has changed?

BLB: I don’t think there is, or can be, an underground anymore with this whole paradigm shift of being on the grid and how corporate things are. The new generations are born into a corporate reality that for my generation was anathema. It’s an interesting time because it’s kind of like, in one way you can see it as late capitalism, or as the decline of something.

SM: Like, this is when everything falls apart?

BLB: But those are the most interesting times because everything is up for grabs and full of possibility.

The Visitor will be showcased in October 2023 at a/political.