In his diaries from 1979, Sean DeLear shared encounters shoplifting gay porn and hustling in LA without shame or pretence. Now, Semiotext(e) has published them for the first time

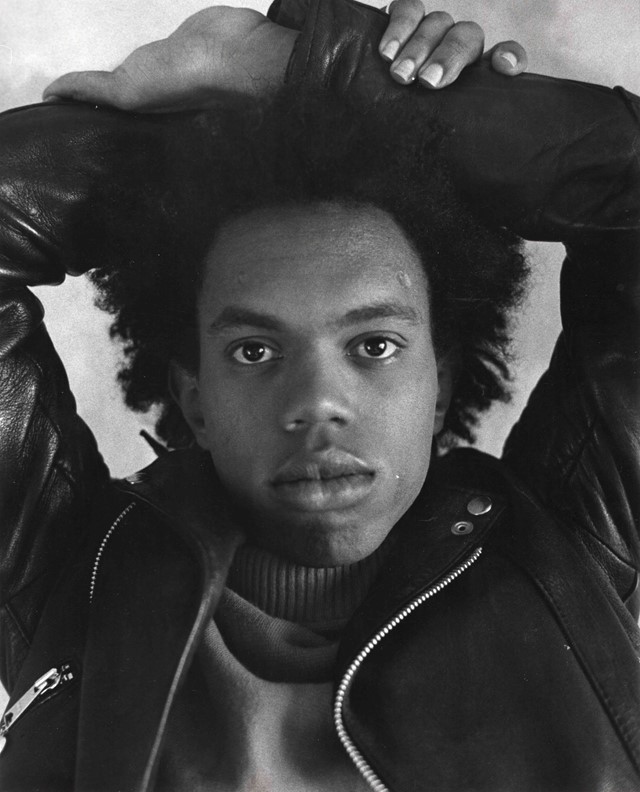

As the clock struck midnight on New Year’s Eve in 1979, 14-year-old Sean DeLear penned his very first diary entry: “I will write everything that happens to me in 1979.” Almost every day for a year, the precocious teen deftly penned scenes of daily life as a queer Black boy coming of age just before the advent of Aids.

Growing up in an evangelical Christian family who were among the first Black residents of Simi Valley, a notoriously racist suburb of Los Angeles, DeLear (then Anthony Robertson) fearlessly embraced all aspects of his identity with singular aplomb. Amid tales of crushes, family squabbles, and ditching school, DeLear shared intimate details of his encounters shoplifting gay porn, hustling, and even blackmail without pretence or shame.

The diary came as a revelation and a delight to DeLear’s friends, who discovered the notebook among his things following his death. “I couldn’t believe the personality that I knew was already fully formed at 14. It’s so funny that his best friend, Jeppe Laursen, wrote Born This Way, because he really was born this way,” says Cesar Padilla, who teamed up with Michael Bullock to edit the new book, I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear, published by Semiotext(e).

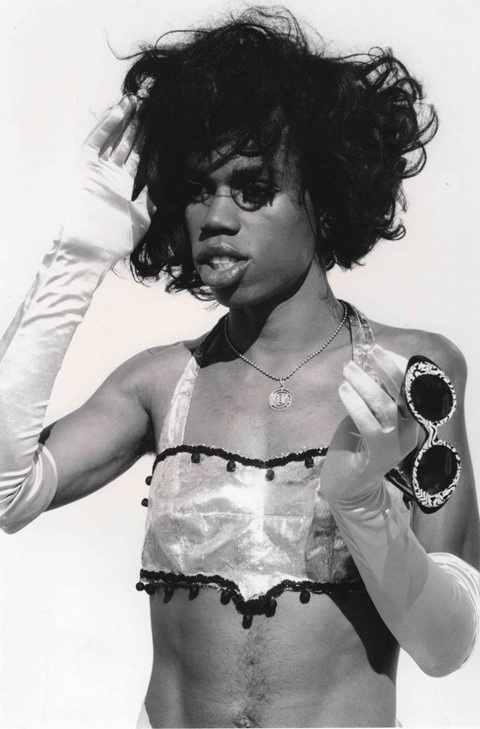

As one of the “First 50” LA punks, DeLear (“SeanDe” to his friends) was the heart and soul of the city’s “Silver Lake” scene in the 1980s and 90s. Described as “Los Angeles royalty” by the LA Weekly, DeLear collaborated with legends like Kembra Pfahler and Vaginal Davis. He made an unforgettable cameo in the 1989 music video for Tone Loc’s top 10 hit, Funky Cold Medina, delivering the line: “But when she got undressed / it was a big old mess / Sheena was a man.”

DeLear blurred the lines between race, gender, sexuality, and style long before there was any language to describe his life and art. Whether working as a video vixen, dance-track vocalist, back-up dancer, hostess at LA’s legendary Viper Room, or babysitter for young Frances Bean Cobain, DeLear followed his own star, defining success on his own terms. As the diary shows, he maintained this mindset from the very start, whether hustling on Santa Monica Boulevard, getting a fake ID in hopes of visiting gay bathhouses, or dreaming of interviewing Charles Manson for Playboy.

Padilla and Bullock immediately recognised the literary brilliance of DeLear’s writing. Without pretence or self-consciousness, DeLear lived his truth on and off the page. “Finding this diary was like finding the Rosetta Stone,” says Bullock. “It expands the boundaries of what it means to be queer and what freedom looks like.”

Amid the canon of coming-of-age novels and teen diaries, DeLear’s crisp prose stands on its own. Gloriously unapologetic, DeLear details his sexual adventures with pride. “This is one of the best books I’ve ever read because most queer coming-of-age stories are about being beat up, how much you suffered, and then how you overcame the pain and shame to become your true self,” says Padilla. “This is the first queer coming of age story that is about joy and pleasure. It’s not that he didn’t have adversity; it‘s that he had a really good attitude about whatever he was dealing with.”

As the 1970s came to a close, DeLear revelled in the freedom of being a libertine, whether hanging out with friends at the roller disco or picking up tricks. “There’s nothing that speaks to the ‘morality’ of something bad and it’s so refreshing to read something like that,” says Padilla. “It’s unbelievably honest and the prose in that book is just mind blowing. I keep reading sentences to Michael like: ‘They had a cake for Gina the whore.’ That’s the most perfect sentence I’ve ever read. It’s straight out of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer.”

Like Miller, DeLear’s candor and exuberance calls into question the narrow confines of sexual morality, creating space for conversations around sexuality, promiscuity, and sex work. “Many gay men have had early sexual encounters with people over age, but it’s so taboo in our society to talk about it that most people just suppress their formative experiences,’” says Bullock. “What makes this book so powerful is that Sean is so confident about his sexuality from the start.”

Blessed with knowledge of himself from a young age, DeLear embraced his desires without judgement or shame, showing just how delectable life can be when you are ready, willing and able to follow your heart’s desires. He walked it like he talked it, without needing to squeeze himself into a box to meet anyone’s expectations of who he was. “Today there is a rush to identify and label yourself,” says Padilla. “But this book is like, just be yourself and you will form. There’s no hurry.”

I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear is published by Semiotext(e) and it out now.